You have worked for many years on the ethical dimensions of development and know very well the trajectory of the capabilities approach. How do you think we should rethink the concept of human development in the current context?

I believe that the current situation created by COVID-19 shows us one very important issue: our lack of capacity to anticipate key challenges for human development. I believe our societies have focused too much on predicting what will happen in the near future, and this means we have failed to think about longer-term options for the future. This fixation on predicting what will happen spreads to all areas of life, from sports to the economy. It seems we are uncomfortable debating what could or should be done and end up more interested in what is likely to be done.

This normative impulse was the defining characteristic of the Human Development Reports. I believe we should keep the spirit of this visionary thinking about what the future should look like, combined with the best empirical work about how things are and how they can change. The core idea that development should be not guided by data, but guided by norms and values, needs to return to centre-stage.

Clearly, one important issue in this normative exercise is to envision what our obligations to future generations should be. Development for the future is something that needs to be more carefully articulated than in the past. If we continue along the development trajectory of today, we are going to be facing major catastrophic situations. Our ethics will need to change, because some people are going to have to forgo certain ways of living if we’re going to survive. We see some of this today, with the reopening of our societies when the peak of the pandemic starts to recede. Some even argue that the social and economic pressures for reopening societies means that some will have to die for the sake of economic recovery and we need to accept that sacrifice. It is frightening, but it is the attitude of many today and this requires moral critique.

Philosophers have dealt with the general question of justifiable sacrifice. But now they need to deal with it in a very concrete policy situation. I think we can learn something from the present situation regarding the options of future generations. To avoid a future catastrophic situation and foresee a normatively guided vision of the future, we need to make changes today, even if these are painful and costly. The sacrifices, however, must be freely adopted and fairly distributed.

A second key area that is fundamental for the rethinking of human development is related to governance. I have worked for many years on democratic governance. More than a decade ago, this was a central topic in the UN’s development work. But democratic governance is even more important and called for today. Current levels of inequality and imbalances in power means that the voices of people – especially powerless people – must be heard and become influential in local, national and global debates. There is an urgent need for all types of people and groups to be actively involved in the creation of our common future. A pertinent example is the ‘Black Lives Matter’ response to racial injustice in policing and incarceration in the United States.

Governance is about process and clearly there are many different conceptions of democracy. But most of them are thin and incomplete. We need a strong, deep and inclusive view of democratic governance to guide the rearticulation of human development, to guide social change. When looking at what is happening in the United States today, when a minority has decided to reopen our society too early and too fast, those voices that challenge this reopening are silenced, the voices of women, minorities and the vulnerable.

Good democratic governance is about broad participation, especially of those who have been overlooked and repressed in the past. To me, this simply means that good development is about democratic development. This combination will and should take different forms in different contexts. Bringing development and democracy together in creative ways should be the basis for development and assistance, as argued by Thomas Carothers, the director of the Democracy and Rule of Law Project at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Another key element that is fundamental for our rethinking of human development is anti-corruption. Certainly, corruption is related to good governance. A responsible public leader is one whose basic aim is to serve the public or common good rather than enrich oneself, one’s tribe, or one’s family. Corruption is about, among other things, personal responsibility and personal ethics. We all know that corruption is bad and we can define it in different ways. But we are all tempted by it in various ways, small and large. This is why it is so important to understand the role of normative commitments and ideals.

Tell us more about the importance of development ethics.

The most important challenge I see with development ethics today is to bridge the gap between theory and practice. We see this concern clearly in the efforts of Chloe Schwenke and others in the LGBT movement. But there is much more to be done. The fundamental challenge is that development teams – at whatever level – must have close collaborations with ethicists or ethically concerned practitioners. Yet this rarely happens. All development work entails value choices that need to be brought to the surface, to ensure they are seen and evaluated. In her 2020 memoir, The Education of an Idealist, Samantha Power illustrates ways of making relevant moral arguments in high-level policy decision-making.

Ethicists are also needed because all development work – planning, execution, evaluation, modification – should have a local emphasis. We do not need outside ethicists who just bring in blueprints they may have developed for another part of the world. What is needed is their effective involvement in, and ongoing dialogue with, local communities and people. This is the way to ensure that challenges such as inequality, gender injustice and corruption are confronted, so that the participation of vulnerable groups plays out in concrete situations.

Normative or ethical training is important, because if done in the right way it can bring to light these issues and challenges. Of course, some professionals care a lot about these matters – human costs and the impact of different development programmes on people – but an expansion of this ethical inquiry would improve the outcomes and enable better implementation of visionary views on human development.

In short, I think that the dimensions of our concerns for humanity and visionary thinking on what ought to be, concerns for future generations, and emphasis on democratic governance and corruption, alongside ethical guidance, need to be core components of rearticulating human development.

What are the key challenges today to that idea of human development?

I believe that climate change is a first major challenge. The second is a substantive democratic deficit and related to this is the resurgence of authoritarianism. Both challenges are connected because autocrats love to discount the future; they want to make as much money and profits as possible in the present.

The pandemic shows us how fragile our ecology is, but also how we are all connected to one another. We have also seen glimpses of how the whole global system could collapse in ways that we have not envisioned in the post-World War II or even the Cold War periods. I think that the pandemic shows us the kind of radical rethinking that we need to do. Politicians in the United States like Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders have been saying this for a long time. We cannot simply just tweak things; we need to get to the underlying causes and aspire to realize humane values. The social and economic inequalities in the world today are fundamental challenges facilitating the spread of authoritarianism and undermining democracy. The short-termism that colours the views of authoritarian regimes is the biggest challenge to finding a solution to climate change as well.

How can we then make human development more relevant for policy and decision-making?

I believe we need to continue putting normative concerns at the centre of human development and show that measures like Gross Domestic Product are at best a means to human ends (and often not very good ones). Bridging the gaps between academics, policy-makers and those in the development trenches is another way to demonstrate the relevance of human development.

Ethical guidance for development work has not been influential, like say the way in which animal rights and animal ethics have successfully influenced attitudes and polices towards the treatment of animals. The comparison may seem strange, but it is very instructive to see how animal rights has succeeded in changing local and national legislation governing the treatment of animals. See, for example, the writings of Bernard E. Rollin in A New Basis for Animal Ethics: Telos and Common Sense.

Another way to improve impact and promote change is to practice more immersion in the lives of local communities. Even development professionals in the World Bank realized that having a sabbatical where one would go and live in a village was much more efficient in understanding development problems and solutions.

To conclude, how would you define human development in a manner responsive to today’s challenges?

I think we need to define development as freedom, as simple as that. The original definition of living the lives people have reasons to value, even if complex and abstract, still captures the core concerns that I have outlined. The vision that there are certain human capabilities that are valuable in and of themselves is key. But to me the most important capability is agency. It is a kind of super-capability, as it enables us to decide what the other capabilities should be. In some sense the result is transcultural, not in some spooky Platonic sense, but relevant for people anywhere in the world. The notion of being not just free from constraints but free to run your own life with other people together remains, I think, a core value. A focus on agency tells us all that people – individually and collectively – should never be treated as things but rather as people responsible for their own lives.

Together with agency, I believe that holding onto equality and well-being is key for a meaningful definition of human development today. But I believe there is a lot of work to be done in making this vision of agency, equality and well-being attractive, as well as accounting for sustainability and future generations. For recent work in international development and development ethics, including three of my new essays, see the Festschrift (Hominaje) Agency and Democracy in Development Ethics (2019), edited by Lori Keleher and Stacy J. Kosko.

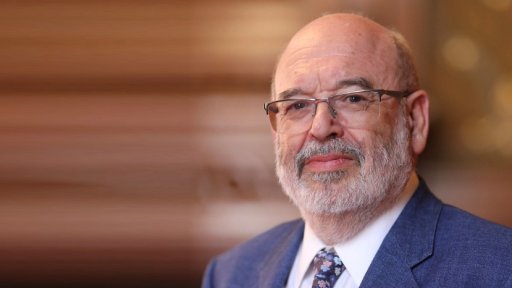

David A. Crocker is Senior Research Scholar Emeritus at the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy and the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. He specializes in socio-political philosophy, international development ethics, transitional justice, democracy and democratization, and the ethics of consumption. He is the founder of the International Development Ethics Association.

Cover image: by Fernando @cferdo on Unsplash