Technology such as this, in combination with new approaches to give voice to marginalised people, is helping rethink common perceptions of remote areas and the people who live there. Through more democratic use of images and technologies, an individual with a smartphone and access to the internet, along with the right support to speak up for the value of their way of life, can challenge traditional ways of research.

“We know that scientific methods can tell us a lot about the environment. But we also learn a huge amount from listening to the people who know it best, and telling stories through photographs also helps to reveal insights and perspectives that would otherwise be invisible,” says Professor Lyla Mehta, principal investigator of a social science project called TAPESTRY1, which, with a local partner Sahjeevan, looks at three patches of transformation in vulnerable coastal areas in India and Bangladesh, including the Kutch mangroves.

The importance of involving communities in research has been recognised by the International Science Council (ISC) which, together with the Belmont Forum and NORFACE, is funding TAPESTRY and 11 other research projects under the Transformations to Sustainability programme, which supports social scientists to lead research on sustainability. The key to TAPESTRY’s success has been to turn the traditional research process on its head; the knowledge originates from conversations and discussions with the local people themselves combined with photos, surveys, site mapping and satellite imagery to get a more complete picture of what’s going on.

TAPESTRY’s outcomes will inform processes to improve the quality of life and wellbeing of people affected by climate change-related uncertainties, while also generating evidence of how bottom-up transformations can take place in remote environments.

1 TAPESTRY: Transformation as Praxis: Exploring Socially Just and Transdisciplinary Pathways to Sustainability in Marginal Environments

In Kutch, for instance, there was a perception that camels damage the mangroves, which protect the coast from storm surges and provide habitats for wildlife. From the point of the view of the camel herders, backed up using satellite data, the camels don’t harm the mangroves and can actually make the mangroves more liveable for small animals by making them bushier, rather than taller, as they nibble only the top leaves. Additionally, the market for camel milk is growing and with bigger companies getting involved, there is a potential commercial justification in protecting these rare camels. At the same time the pastoralists are also simply trying to preserve their traditional culture and way of life.

In weighing up the economic advantages of developing an area with its environmental impact, what the TAPESTRY project shows is the importance of supporting pastoralists and other voices to share their knowledge and concerns.

Professor Mehta adds that one of the challenges of the project was to confront the misperceptions of pastoralists, who need access to the mangroves and space to move. “The conventional Gujarat model of development largely focuses on infrastructure and industrial development”, she says, pointing out that by not taking the rights to the common land and natural resources of poor and marginalised coastal dwellers such as fishers, pastoralists and farmers into account, further damage can be done. “Industries built along the coast have not only destroyed coastal ecologies but also prevent them and their animals from accessing vital coastal resources such as mangroves.”

Now, with the help of the team at TAPESTRY, coastal zone management committees have been formed to monitor the restoration of the mangrove cover and to prevent further degradation of mangrove habitat. The result is a positive impact on the traditional livelihood of the pastoralists and the camel milk economy, not to mention environmental sustainability, as the mangroves harbour wildlife and protect against violent storms.

Other groups that have had successful outcomes as part of the TAPESTRY project include the traditional Koli fishers of Mumbai. Using social science, community activities and engagement with authorities, researchers helped the fishers develop responses to overfishing, disruptive infrastructure projects and pollution. This involved working with Bombay61, an architectural practice run by members of the Koli community, as well as a conservation NGO and researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

Meanwhile in the Sundarbans, a Unesco-protected mangrove habitat that straddles the border between India and Bangladesh, TAPESTRY researchers are working to understand how islanders are coping with rising salinity from storms and how they are carving out new livelihoods with innovative methods from aquaculture and crab farming to new crops while also building alliances with civil society and NGOs. In this region TAPESTRY is also working with schoolchildren through art projects to document their perceptions of uncertainty, which at the moment is exacerbated by the instability caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

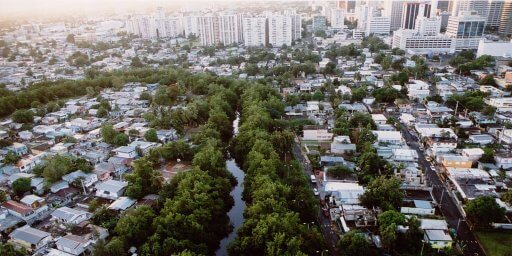

Another project funded by the ISC is MISTY2 , which focuses specifically on the growing migration into cities and makes recommendations on how to develop safe and sustainable cities inclusive of migrants. For instance, in Chattogram, Bangladesh, migration from the low-lying coastal areas of the country as well as by ethnic minorities from the Chittagong Hill areas, has seen the city grow threefold to over five million people in one generation, yet large swathes of the city are made up of informal settlements such as slums which are excluded from planning for services.

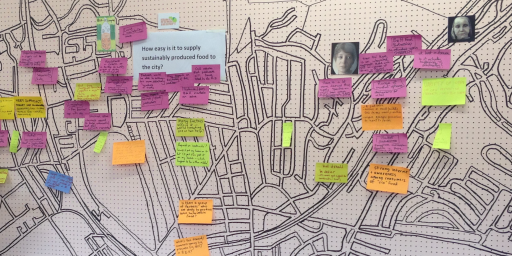

In this project, MISTY researchers encouraged both planners and migrants to document their experience of the city by taking photographs and then sharing them and the stories behind the photographs with each other.

While the city planners initially took photos of road congestion, lack of garbage disposal facilities, encroachment of footpaths and roads by vendors, new migrants highlighted the day-to-day precarity of their lives and livelihood. Their photographs depicted the hardship of balancing long working hours with trying to upskill through education in order to enhance their employment and income prospects. At the same time, the images reflected what it was like to endure poor housing, limited access to basic facilities, and multiple health and safety hazards characteristic of low-income neighbourhoods.

When the two parties saw photos they began to appreciate the challenges identified by each other. In the end, both parties learned from the exchange.

“The photographs taken by planners and migrants are so powerful,” said Professor Tasneem Siddiqui, MISTY co-investigator and co-founder of the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit at the University of Dhaka. “They showed the common experience of everyone, and the challenges of sustainability. And sharing the photographs with each other really helped planners stand in the shoes of others and gave them confidence in the direction of planning for services and infrastructure. This social science research method really helped to give voice to the voiceless, a key to sustainability for everyone.”

The result of this project has been that planners in Chattogram publishing the city’s Five Year Plan now ask for the input of its citizens, encouraging them to take photographs and discuss their needs.

“This social science research method really helped to give voice to the voiceless, a key to sustainability for everyone.”

Professor Tasneem Siddiqui, MISTY co-investigator and co-founder of the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit at the University of Dhaka

The TAPESTRY and MISTY projects are funded by the Belmont Forum, NORFACE and ISC Transformations to Sustainability programme, which is jointly supported by AKA, ANR, DLR/BMBF, ESRC, FAPESP, FNRS, FWO, JST, NSF, NWO, RCN, VR and the European Commission through Horizon 2020. The ISC is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

This article has been reviewed by Robert Lepenies, Karlshochschule International University & Global Young Academy and Elvis Bhati Orlendo, International Foundation for Science, Stockholm.

Paid and presented by the International Science Council.