The Ocean Decade begins in 2021. What do you want to achieve by the end?

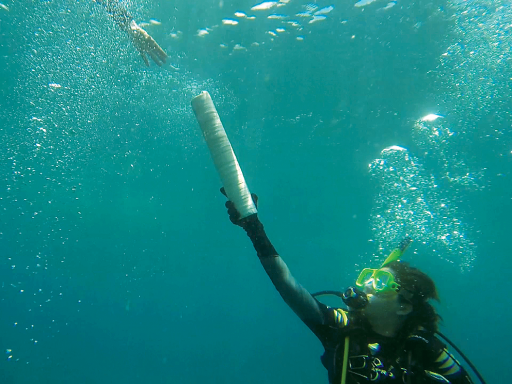

At the moment, only around 10% of the ocean’s make-up is understood by science. For example, pretty much every time you sink a bucket down into the deep sea, you find some new microscopic lifeform when you pull the bucket up. We have so much work to do in ocean science; think just of what’s involved in mapping the seafloor or the ocean’s biome. Thus, we need at least a decade to get that work done.

We have some very important decisions to make about our relationship with this planet and we need to make them on the basis of solid science. In that regard, with the ocean covering 70% of the planet, 10% scientific knowledge about it is clearly insufficient. That is essentially why the United Nations General Assembly mandated the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development: to give us the solid science we need to make sound decisions in the future.

I believe that what’s happening in the ocean will determine the survival of our species. The IPCC special report on global warming tells us that once we go over the dreaded line of 2˚C above pre-industrial levels, we lose what’s left of the planet’s living coral reefs. Coral reefs are home to around 30% of the ocean’s biodiversity. If you take 30% of the ocean’s biodiversity away, do you have a healthy ocean? Surely not. Can you have a healthy planetary ecosystem without a healthy ocean ecosystem? No, you can’t. The ocean is the most important element of this blue planet, and that’s why I say that our fate may be closely linked with that of coral.

We’re now in the preparation phase for the Decade. How is it going?

I’m very satisfied with the preparatory process. I think the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC-UNESCO) has done a superb job going out to all the regions of the world for wide-ranging, inclusive consultations. Given their importance to the Decade, I’ve sent out pre-recorded video messages to all of these regional meetings, encouraging all those involved to contribute to the success of the planning and implementation of the Decade of Ocean Science.

Are there any scientists that you would like to hear from in particular, perhaps from certain disciplines or certain regions of the world?

It’s a very wide field. Personally, I’m convinced we’ll find the medicines we require for humanity security from comprehensive scientific understanding of the genetic properties of life in the deep sea. I’m also convinced that when we get to know more about the ocean biome, we’ll be able to source new sustainable forms of food, rather than hunting ever-diminishing wild stocks of finned-fish. In terms of energy, from what I understand we can get ten times our energy requirements just from ocean wind alone. Which is where ocean science comes in, for we must fully understand the ocean ecosystem when we make these major moves into the sustainable blue economy.

How can the scientific community get involved with the Decade?

The Decade relies heavily on the scientific community. I come from Fiji, where I’ve been working with the Pacific’s regional institutions to make sure that this Decade is something into which the Pacific Islands are fully integrated.

And given its growing importance, I’ve been encouraging young people around the world to consider ocean science as a worthy career-path.

The Decade will be a time of partnership, for philanthropists, for universities, for NGOs, international organizations and the private sector. I see it as a time to really strengthen the partnership model that the UN has been endeavouring to foster through multilateralism.

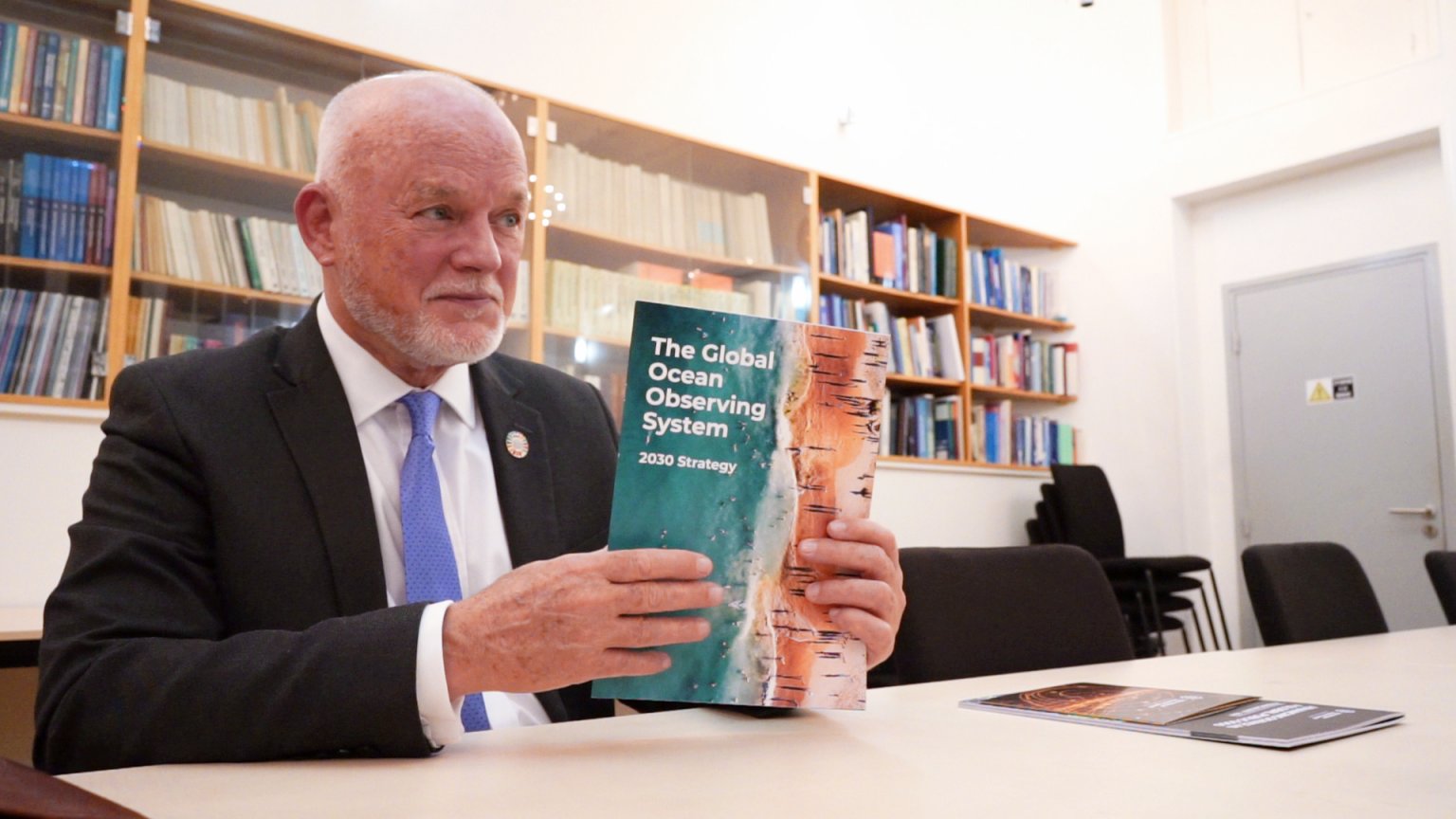

I’m really glad that the International Science Council is part of the Global Ocean Observing System along with the World Meteorological Organization, the UN Environment Programme and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO. We’ve relied on this observing system for so much information in the past and will need to scale that up for the Decade. It’s truly an excellent example of effective partnership.

One of the aims of the Decade is to promote ocean literacy. How do you think the scientific community can contribute to building curiosity and interest in the ocean among the wider public?

I think levels of ocean awareness have rocketed. What child do you know who’s not fascinated by dolphins, penguins and seahorses? Actually, I’d say that all age groups are upping their awareness of what’s going on in the ocean and I give credit to the scientists and the media who’ve been mostly responsible for that rise.

The ocean is becoming acidic and its oxygen levels are falling, with both these trends accelerating. Left to their current course, rising sea levels will inundate atoll countries, low-lying coasts and river deltas around the world. Mega cities on alluvial lands along many coasts will also be flooded. These are existential challenges, and all those things are coming at us fast these days. Mostly because of these threats I think, people are getting it. I think where we were with ocean literacy five years ago and where we are today are two different levels; but we still have a long way to go, so bring on the Decade.

What about the policy community – are they getting it?

If you talk about ocean and climate and biodiversity in the same breath, and ask yourself whether world leaders are getting it and whether they are changing policy fast enough? I think the jury’s out on that. As everyone knows, there are some very prominent ones who do not seem to be getting it.

Without doubt, it’s hard for government leaders, with all the responsibilities they have, to make the kind of investments in transformations that are going to be required to keep us below 1.5˚C. We’re talking about completely different ways of consuming and producing, unprecedented changes in all aspects of society. That’s what’s required to get our greenhouse gas emissions under control, because they’re rampant at the moment.

We know what the effects of those escalating trends will be, such as massive wild fires, increasingly destructive hurricanes, flooding, famines, pandemics and, yes, the death of coral. Sadly, my home region of Australia and the Pacific Islands are experiencing most of those effects already.

I think the policy community, our political leaders, understand that changes have got to be made to meet the climate change challenge. Perhaps the biggest part of the challenge is to get the big emitters to agree to act in concert to bring down anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. The place where we really want to see that concert in action is at the next UNFCC COP in Glasgow, where we want to see governments come along with greatly enhanced nationally determined contributions. The ocean community’s main message to them is that only through dramatic curtailment of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions will we be able to have confidence in the future health of the ocean and thereby our own.

This is part of a series of blog entries on the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (also simply known as the “Ocean Decade”). The series is produced by the International Science Council and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, and will feature regular interviews, opinion pieces and other content in the run-up to the Ocean Decade launch in January 2021.