On the 15th of March 2020, as it lay in the calm waters of Cape Town, the oceanographic research vessel Ronald H. Brown was about to be caught in the cross-hairs of the coronavirus outbreak. Dr. Leticia Barbero of the University of Miami, the vessel’s Chief Scientist, was notified by the captain of instructions to return to home port of Norfolk, VA, immediately. “It was a shock,” said Dr Barbero.

“Overnight, our vessel transformed from a research ship observing a decade’s worth of ocean changes, into a simple express steam home.”

Amid the uncertainty of this unprecedented recall, the science team aboard the Brown proactively prepared and deployed over fifty autonomous instruments, including ocean drifters and profiling floats, across the South Atlantic and Caribbean, to ensure that measurements vital to climate and weather prediction would continue to flow in their absence.

“Three months later, it is clear that this quick action has helped maintain critical operations for two of the global ocean observing networks in the Atlantic Ocean,” says Dr. Emma Heslop, Programme Specialist at the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) Secretariat. “We need to act collectively if we want to maintain critical function and data flow for weather, climate and ocean health services on a global scale.”

Dr. Heslop is part of the team within the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) that conducted a survey to assess the impacts and forecast the pandemic’s risk to global ocean observations. She said that “the survey went out to the eleven global ocean observing networks of GOOS – each focused on different ways to observe the ocean”. This global ocean data is essential to developing reliable weather forecasts as well as to understand and predict climate change. A wide range of industries rely on a daily basis on these data, from farming to global shipping.

“The results of the survey and the issues uncovered are a key part of the learning and sharing processes between countries that we support,” said Vladimir Ryabinin, Executive Secretary of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, the UN’s main ocean science body that also coordinates the GOOS.

“This will allow us to pivot towards having leaders in ocean science engage in common priorities and cooperative action to sustain key observations and flows of data.”

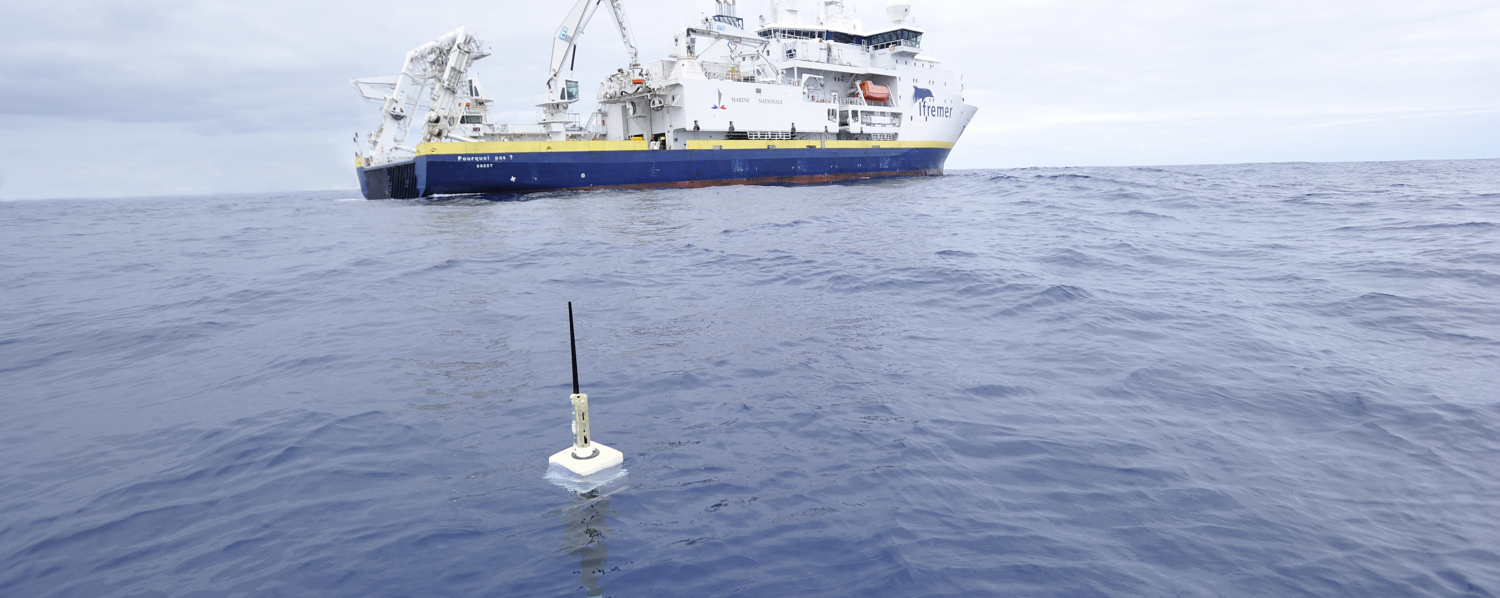

Around the world, as governments and oceanographic institutes recalled nearly all oceanographic research vessels to home port, the impact on our ability to observe the ocean has been dramatic. Even where autonomous equipment such as moored buoys (fixed instruments that scan the whole “water column” from seafloor to the sea surface to provide a wide array of ocean data) or Argo floats (free-drifting floats that provide information about ocean temperature, salinity, currents and biological properties) are used, maintaining the equipment in the absence of regular scientific missions is a challenge.

“There is a real risk that equipment will fail, resulting in the loss of both data and potentially the equipment itself, like the moorings,” explains Dr. Johannes Karstensen, co-lead of the OceanSITES time-series network. The loss of even a single one of the over 300 operational moorings could mean a gap of two to five years of data. Dr. Karstensen said that “30-50% of moorings will be impacted by the pandemic, and some have already ceased to send data. Considering that this equipment not only monitors vital information for the ocean economy but monitors long-term climate change, it is clear that maintenance missions need to be prioritized as an essential activity in the context of COVID-19 regulations.”

Perhaps most strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic were the observing operations within the “Ships of Opportunity Programme”, which uses commercial and other non-scientific vessels to take vital ocean measurements. Scientific “ship riders” normally deploy the observing instruments, but COVID-19 restrictions mean that they can no longer operate aboard.

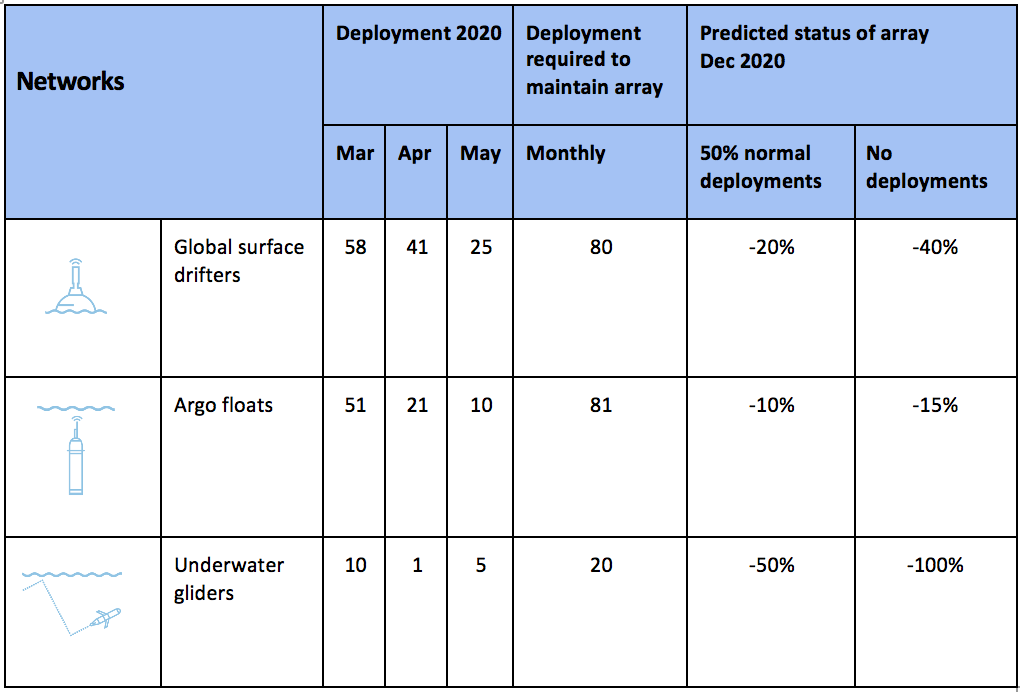

The slowdowns in deployment and maintenance of autonomous instruments, such as drifting buoys, drifting floats and underwater gliders, is equally challenging. Though these instruments are more resilient, operating autonomously for months to years after being deployed by scientists, they need regular maintenance or redeployment, also impacted by pandemic restrictions.

The system has shown resilience to the immediate impacts of pandemic-related shutdowns, as global observing networks were well-maintained going into the crisis and increasingly reliant on autonomous observing instruments. However, COVID-19 restrictions have already reduced the level of deployments needed to maintain a sustained flow of weather and climate forecast data (see figure). Without urgent international action to support ocean observing operations by the end of the year, we could see further significant disruptions with potentially devastating consequences.

Within the last month a worrying 10% reduction in the flow of data from the Argo network has been detected. “It is too early to tell to what extent this is due to COVID-19” says Mr. Belbeoch, leader of the observing system monitoring unit JCOMMOPS, “however the very low level of recent Argo float deployment compounds the situation, and this drop in data flow cannot be immediately remedied.”

“The weather forecasting systems will run off the rails if they don’t have the surface pressure information over the ocean to constrain them” said Lars Peter Riishojgaard, Director of the Earth System Branch at the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “We cannot do reliable forecasting without this piece of information coming straight from the ocean via these drifting buoys.”

Even as countries start to ease quarantine and confinement restrictions, ocean science may not necessarily be at the top of decision-makers’ priorities. Among countries planning to restart research vessel operations in July (Australia, Finland, Belgium, Netherlands, New Zealand, Germany and US), important restrictions will still apply – such as the requirement that vessels leave and return through the same home port – which largely diminishes the area covered by research vessels.

There is a real concern that research vessel operations in some regions may not resume at all in the coming months, with impacts extended to the end of 2020 and possibly into 2021, when also considering related impacts on the supply chains for some of the observing instruments.

“Despite its significant impacts on the ocean observing system, the COVID-19 crisis can also be an opportunity for us to look at how to build greater resilience into our system,” argues Dr. Toste Tanhua, Co-chair of the Global Ocean Observing System. “The impacts of COVID-19 have brought to light the inter-reliance of systems and some clear weak points that we can now work on to increase system efficiency and robustness.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic has also shown us the importance of developing pathways from science into societal solutions,” highlighted IOC’s Executive Secretary, Dr. Ryabinin. “That is true for ocean science as much as for health science, and even now IOC has been solidifying plans for a UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021-2030, that will harness research and develop transformative ocean science solutions, connecting people and the ocean.”

Partnerships across political borders and operational flexibility may be what it takes to carefully organize the various actors undertaking ocean observations in the face of ongoing disruptions. Moreover, international agreement to classify global ocean observing operations as essential activities could ensure that the global observing system better delivers critical information to weather forecast, warning systems, climate and ocean health applications into the future.

The Global Ocean Observing System has issued a briefing note on Covid-19’s impact on the ocean observing system and our ability to forecast weather and predict climate change, which highlights five key recommendations for avoiding significant long-term loss to the system.

Under a Memorandum of Understanding, the IOC of UNESCO, WMO, UNEP and ISC are responsible for co-sponsorship of the GOOS Steering Committee (GSC).

For further information, please contact:

Emma Heslop, Programme Specialist, Ocean Observations and Services Section / GOOS Secretariat, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO ([email protected](link sends e-mail))

Photo: NOAA