Global conflict displaces millions of people, among which are some of the brightest academic minds. If they are unable to continue their work, we risk losing their knowledge forever.

No one knows the true number of globally displaced scientists and academics. One estimate from 2017 suggested it could be as many as 10,000. The reemergence of Ebola in West Africa in 2017, the peak of war in Yemen in 2020 and this year’s instability in Afghanistan are just some of the humanitarian challenges that are likely to have exacerbated the problem since that estimate.

In 2020, just five countries accounted for two-thirds of all refugees: Syria (6.6 million), Venezuela (3.7 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million), South Sudan (2.2 million) and Myanmar (1.1 million). In Syria alone, there might be 2,200 academics among those refugees.

A number of programs help refugees integrate into and contribute to a host country, among them the At-risk Scholars Initiative of the Global Young Academy. Since its beginnings in 2017, the initiative has tried to unite volunteer mentors with at-risk scholars who might otherwise drop out of their respective fields due to conflict or crisis.

Many international and national organisations provide temporary scholarships and placements at universities for at-risk or displaced scholars from around the world. The Global Young Academy (GYA) At-Risk Scholars Initiative cooperates closely with such organisations, including Scholars at Risk, the IIE Scholar Rescue Fund and Cara. Having arrived in their new countries of residence, mentees are referred to the GYA initiative for additional, personal career support through peer mentorship.

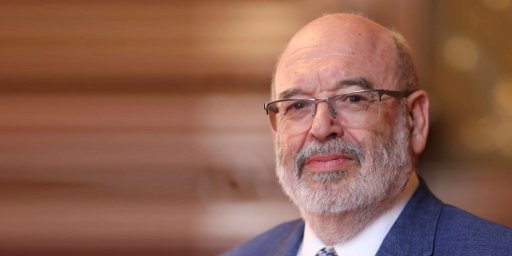

We risk losing an entire generation of scientists, engineers, medical professionals, and arts and humanities scholars –

Teresa Stoepler

The initiative was established by members of the GYA, an independent scholarly academy that brings together exceptional young scientists to work across geographical, cultural and political boundaries to address pressing global issues.

“We risk losing an entire generation of the best and brightest of these countries, including scientists, engineers, medical professionals, and arts and humanities scholars,” says Teresa Stoepler, co-lead of the At-Risk Scholars Initiative alongside Lisa Herzog.

Scientists forcibly displaced by conflict and humanitarian crises also work in some of the world’s poorest-funded academic institutions. In some cases, like in Iraq and Syria, strong and-well established scientific institutions have now been lost to war. In Syria, for example, the scientific, medical and engineering institutions were among the most respected in the Middle East before the 2011 civil war.

Making the decision to move in the first place can be challenging. In Syria, and many other countries outside the West, scientists are employed as civil servants; their jobs are comfortable and secure. Some might be reluctant to leave their country and the relative security of their employment.

Saja al Zoubi, a development economist teaching courses on gender and forced migration, and Middle East politics at the University of Oxford, left her home country of Syria in 2016 for Lebanon to conduct a comprehensive study about Syrian refugees in Lebanon. After struggling for two years to get a residency visa, al Zoubi had to return to Syria each month to renew her temporary visa.

On one occasion at the end of 2017, al Zoubi was given a one-week visa, which prompted her to apply to several universities in Europe and the US, and eventually she was accepted at the University of Oxford.

al Zoubi was put in touch with the GYA through a mutual friend after her case was featured in a documentary. Her mentor, GYA alumna Karly Kehoe, helped her to adapt to the new scientific environment in the UK by providing help with CV and English academic writing, as well as coaching her through the conventions of British academia.

This was all in addition to the workshops and training that the GYA provides to At-Risk scholars and its members.

Mentors and mentees in the At-Risk Initiative are paired based on similar disciplines and geography. Often, working in the same country is the most important factor, says US-based Stoepler. An ecologist now working in science policy, Stoepler was able to help a theatre scholar find new opportunities in the US despite not being a theatre expert herself.

Displaced scientists face a number of uphill struggles to obtain funding in their host countries. For instance, their qualifications or accreditations might not be recognised in their new country – something that is particularly problematic for medical professionals, says Stoepler.

“They’re launched into a new country, and suddenly have to navigate an entirely new system where they might not know the language very well, don’t know the culture or norms, let alone all of the academic system differences that they might not have been exposed to before,” she says.

Temporary fellowships for displaced scholars are available that provide the researchers with funding for one or two years before they need to seek new sources of income. The risk, according to Stoepler, is that if they’re not able to find new funding and have to return to their home country, it’s possible the situation they were trying to escape might not have been resolved in just a couple of years.

Eqbal Dauqan is a research professor of biochemistry at the University of Oslo. Now based in Norway but originally from Yemen, Dauqan was a mentee of the At-Risk Scholars Initiative who eventually became a GYA member and now serves as a mentor to other displaced scholars herself.

I am also passing my experience to my family… I’m trying to help them –

Eqbal Dauqan

Dauqan left Yemen for Malaysia initially, before successfully applying for funding and securing an academic position in Norway, thanks to her mentor, who helped her write CVs for different applications.

Dauqan’s siblings are also scientists (an associate professor, two medical doctors, two engineers, and one geographer), and are all still in Yemen. “I am also passing my experience to my family… I’m trying to help them,” she says.

Meanwhile, Dauqan’s former PhD student is still in Yemen (she graduated in 2019). Providing feedback on her dissertation and journal articles was difficult; emails can be temperamental in Yemen, so they had to correspond using instant messaging services. Dauqan is also trying to help her former student find opportunities abroad. “I try all my best to help her,” she says, hopeful that one day they will be reunited.

We may never know the true extent of knowledge lost due to conflicts, but the At-Risk Scholars Initiative, and others like it, go some way to help scholars in crises.

Listen to Eqbal Dauqan sharing her story of leaving Yemen to continue her research overseas in the Science in Exile podcast.

The GYA At-Risk Scholars initiative is a founder member of the Science in Exile initiative bringing together a network of like-minded organizations to develop a global platform and roll out a coordinated advocacy campaign, so as to foster a cohesive response for the support and integration of at-risk, displaced, and refugee scientists.

This article was reviewed by Renaud Pourpre, Freelance in scientific communication and Dr Magdalena Stoeva, FIOMP, FIUPESM.

Paid and presented by the International Science Council.