This article is part of the ISC’s Transform21 series, which features resources from our network of scientists and change-makers to help inform the urgent transformations needed to achieve climate and biodiversity goals.

The recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group 1 finds that global temperatures are set to exceed 1.5°C of warming earlier than previously projected, and that if greenhouse gas emissions do not start to decline significantly before 2050, the world is extremely likely to reach 2°C warming during the 21st century.

What does this mean for the Pacific Island Countries (PICs)? Raise the alarm! Pacific Island Countries are on the frontlines of severe climate change, with food, housing, businesses and industries all at risk of increasingly frequent extreme climatic events such as sea level rise, tropical cyclones, and flash flooding. However, despite having miniscule greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, PICs have made bold, ambitious targets to reduce emissions and to promote sustainable and resilient development across all sectors of the economy. They set an example to the other world leaders that the PICs are committed to global emission reductions, and that all contributions matter.

First of all, the main driver for this clean energy transition is having experienced severe and intense natural disasters that cause inestimable damage to communities and economies. Clean energy holds promise for building back better in a more resilient and sustainable manner. In February 2016 Fiji experienced its worst tropical cyclone (TC), TC Winston, a category 5 cyclone which caused havoc when it made landfall amongst the small islands of Fiji, with around 40% of the population impacted by the storm. A total of 44 people lost their lives, and 40,000 homes were damaged or destroyed, leading to shock and negative psychological impacts in the communities affected. Power infrastructure and the forestry and agriculture sectors were also severely affected, with the total damage amounting to FJ$2.98 billion (US$ 1.4 billion). More recently, while battling the COVID-19 pandemic, the PICs have been burdened with the additional challenge of severe tropical cyclones. The category 5 TC Harold hit Vanuatu on 6 December 2020, causing massive destruction to buildings, water sources and agriculture, affecting 33% of the population and claiming the lives of 31 people in the region.

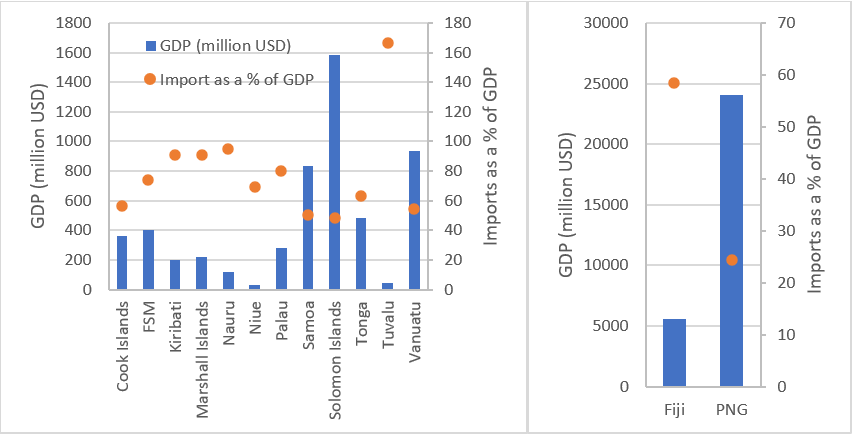

A second driver for the clean energy transition is the high cost of imported fossil fuels. In most of the PICs, goods and services imports make up more than 50% of the GDP, as seen in Figure 2. Using the World Bank database, the calculated average of fuel import in PICs as a percentage of total merchandise imported is 20%. With the exception of Papua New Guinea (PNG), none of the PICs have fossil fuel resources and are entirely dependent on imported fossil fuel. What’s more, because fuel is traded in the international market, PICs have to use their foreign reserves, and are therefore highly vulnerable to volatile fuel prices. Transitioning to clean energy would imply lower fuel imports and an increase in foreign reserves. In the small economies of PICs, with relatively low export earnings and a high dependence on foreign aid, the high prices of fossil fuel have negatively impacted growth.

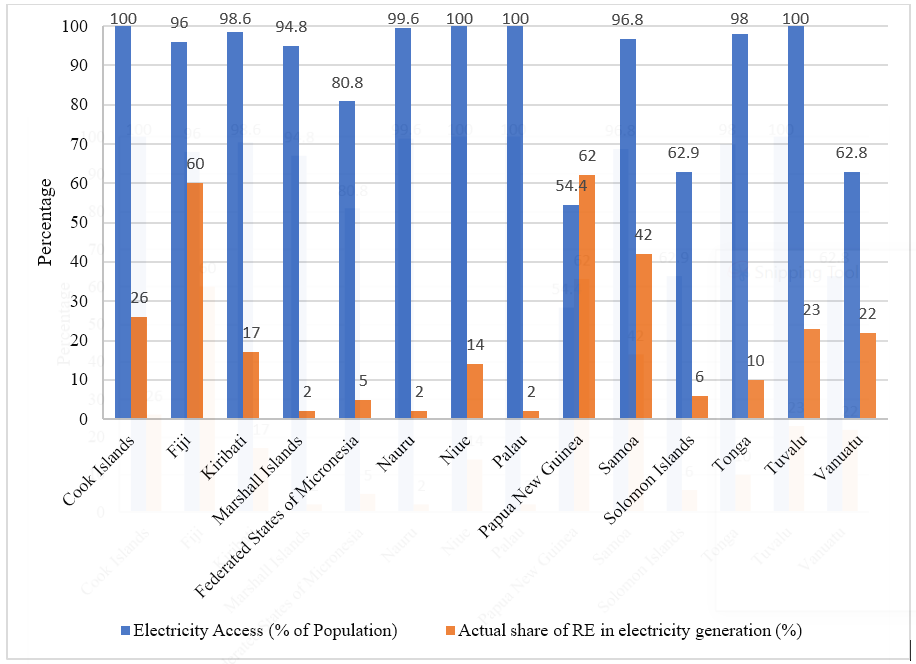

The third driver of clean energy transition is attaining national energy security through improved energy accessibility and a reduction in dependence on imported fossil fuels. As seen in Figure 3, only Fiji and PNG have a relatively high share of renewables in electricity production, with the majority below 20%. In Fiji, around 40-70% of the grid electricity generation is from renewable resources, mainly hydro with little biomass, solar and wind, while the rest is supplied primarily by industrial diesel oil and heavy fuel oil. Fiji’s grid electricity generation from fossil fuel costs on average US$55 million per annum and the cost increases at an average annual rate of 13%. Fiji has 125 MW of renewable capacity for power generation while Tonga has 6.45 MW. Data on clean energy access is lacking, but electricity access data shows varying levels of access in different PICs. In four out of 14 PICs, fewer than 81% of the population have electricity access (Figure 3).

Energy projects typically have two main sources of funding: government funds and donor funds. However, due to other development commitments PICs are heavily dependent on donor funding for energy projects. The Asian Development Bank funded an increase in renewable energy electricity generation capacity of 94.30 MW between 2007 and 2020, and grid extensions helped power an additional 15,646 households. Clean energy transitions would need donor funding to finance projects, build capacity and strengthen institutions in PICs for smooth deployment of clean energy projects. Investments from the private sector are also crucial, but the PICs also need to be able to access financing from development finance institutions.

Clean energy transition has the potential to affect all sectors of the economy, including transport, which is one of the most significant for final energy consumption in PICs. Maritime transport is particularly important, as it provides a means to transport goods and services to remote islands, as well as being essential for the fishing sector. Even though fewer people live in small maritime areas within the PICs, transport is necessary to keep the communities connected and for income-generation activities. The fuel cost for maritime transport can be exorbitant for some essential routes, making the trips uneconomical and creating recurring government expenditure, as these routes are subsidized at times. A modelling study estimated that Fiji’s maritime transport used 79 million litres of fuel in 2016. Transitioning to clean maritime transport would reduce emissions and reduce the burden of fuel costs borne by sea transport operators, commuters and the government. Currently, the Pacific Community (SPC) is the host institution for Maritime Technology Cooperation Centre (MTCC) in Pacific. MTCC – Pacific has been providing trainings to maritime shipping stakeholders in different PICs on ways and technologies to improve energy efficiency in shipping, with innovative and new technologies to reduce emissions and fuel consumption while keeping safety a priority. In addition, because Pacific people are familiar with sailing, local knowledge exists on boat building. With proper incentives and international partnerships, this local knowledge can used to build efficient maritime vessels.

Typically, the main centres of economic activity within a PIC are located on certain islands, in which living standards tend to be higher, but islands further away depend on timely transportation of goods and services. Reliance on imported fossil fuels is therefore a worry, because it increases the transport costs of fuels to remote maritime islands. This rise in fuel cost is usually borne by communities, leading to a disparity in the prices paid by those on the mainland and those in remote communities. In addition, there are instances when the fuel does not reach the maritime islands on time, leading to shortages of fuel and other services and reliance on traditional biomass for fuels. Diversifying energy sources and transitioning to clean energy sources could play a crucial role in achieving reliability of energy supply, ensuring communities continue their normal activities and reducing fuel costs, especially in remote and maritime areas.

PICs have planned to reduce emissions as evidenced by their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and other strategic documents. They are now also implementing some projects with the help of external donor funding. However, to achieve clean energy transition, PICs are faced with many challenges, including geographical isolation and a lack of financial resources, capacity and energy data. There is a need for more data on energy consumption by different sectors of the economy, and on electricity generation from various utilities and industries. The data banks that do exist have limited energy data, as certain industries are hesitant to place their data in the public domain where competitors could access them. Capacity is also lacking, especially with regards to technical expertise on some of the different clean energy technologies and on energy policy, as well as capacity among end-users to operate and maintain their energy systems.

Enhanced partnerships and collaborations are therefore key to clean energy transition. This includes collaboration between different government ministries and departments to synchronize their activities, avoid duplication, increase process efficiency and build enabling policies. Stronger collaborations between government bodies and non-government organizations, civil society and community-based organizations, as well as public-private partnerships, could facilitate more energy projects and programmes. Academic and training institutions also have an important role in capacity-building. Finally, strengthened partnerships between PICs and multilateral and bilateral organizations could support the funding of clean energy transition and work towards resilient and sustainable development in the Pacific Island Countries.

Ravita D. Prasad

Dr Ravita D. Prasad is an Assistant Professor in Physics at College of Engineering, Science and Technology, Fiji National University and specializes in long-term energy planning for low carbon development of energy systems. She teaches Physics and Renewable Energy for undergraduate students and has published several peer-reviewed journal articles. She is also a member of the Commonwealth Futures Climate Research Cohort established by The Association of Commonwealth Universities and the British Council to support 26 rising-star researchers to bring local knowledge to a global stage in the lead-up to COP26.

Header photo: Inspecting solar panels after TC Harold in Kadavu, Fiji, 2020 (Pacific Community (SPC) via Flickr).