Bobbing on mud-brown water in a quiet side-channel of the Amazon River, a teenager called Gabriel and a fisherman called Gilberto sit side-by-side in a wooden canoe. Gabriel is interviewing Gilberto about the fisheries management programme in which their small riverine community has been participating over the past two decades, while another local teen films the conversation on a mobile phone. The community-based management programme “maintains the economy here in the community of Tapará Miri,” says Gilberto, “and it maintains the species so that [the population recovers and] they don’t go extinct.”

The programme they’re speaking of is centred on the arapaima, an immense and ancient freshwater fish – one of the world’s largest and oldest – that is native to the Amazon and Essequibo rivers. Reaching up to three meters [9.8 feet] in length and weighing in at around 200 kilograms [440 lb], they are a critical food and income source for local communities. In the 1980s and 1990s, overfishing led to population decline, and the species became close to extinct in many parts of the Amazon – including the areas around the hamlet of Tapará Miri, which sits near the city of Santarém in the Brazilian state of Pará. But since then, careful collective management – which includes consistent monitoring and clearly-defined ‘fishing seasons’ and catch sizes – has brought the fish back to the community’s waters. Today, there are over a thousand communities participating in the Arapaima management programme in the Brazilian states of Para and Amazonas.

It is an inspiring story, but one that has not been widely shared until recently. Whilst the Amazon is a hotbed of local innovations and efforts to address challenges like land-use conflict, climate change, deforestation, and inequality, these local-level activities tend to be overlooked at higher levels of governance, contributing to the lack of support for and marginalization of the region’s rural and Indigenous communities.

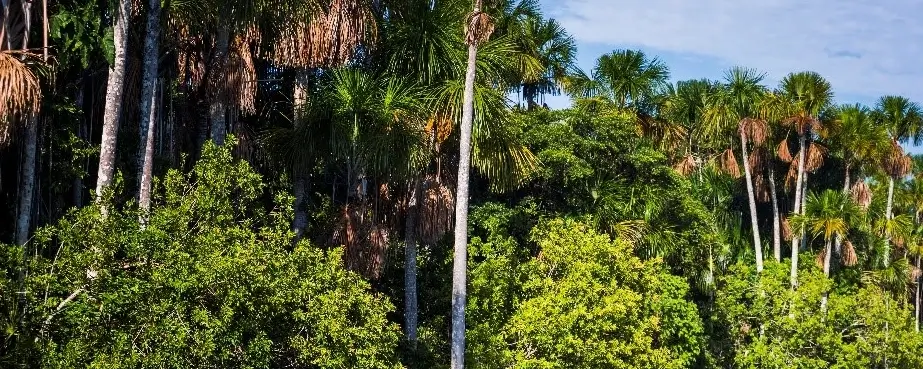

Photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis

That is where the AGENTS project, funded by the Transformations to Sustainability (T2S) programme, aimed to make a difference. From 2019 to 2022 the project sought to document, analyse, and increase the visibility of place-based sustainability initiatives – like Tapará Miri’s arapaima project – in the Amazon Basin. As part of their engagement with AGENTS (which included training on mobile phone-based video production and communication), young people in Tapará Miri created the video – now on the project’s YouTube channel – in which Gabriel and Gilberto appear.

AGENTS has spotlighted a wide range of local initiatives in the Amazon, including agroforestry production systems, forest management, a large-scale seed-saving network, an Indigenous women’s coconut oil enterprise, and a participatory organic certification system, among many others. Most of these initiatives are located in Brazil, with a few in Peru and Bolivia, and many have been operating ‘under the radar’ for decades.

The work has resulted in numerous outputs across a variety of formats, including academic publications and project reports; the YouTube channel; an open letter about these initiatives’ importance and how policies could help to advance them going forward; and a well-attended public event at the local university to share project results with the public. A unique geospatial database was also created, which described around 200 types of initiatives in over 900 locations and over 140 municipalities, including physical, biological, economic, and social data.

“It’s the beginning of a process to give more visibility to people who are doing very important work on the ground, but are largely socially and statistically invisible,” said Eduardo Brondizio, the project lead and an anthropology professor at Indiana University.

“Along with other efforts taking place in the region, we are sending a message and showing concretely that these localized activities – that people do to improve their livelihoods and their local environments – actually have a very big role in the region, because they’re showing a way of reconciling economic development and environmental issues, whilst also confronting a lot of pressures and vested interests promoting deforestation and illegal resource economies; they’re very much on the front line.”

The work also highlighted ways in which power relations within communities could be challenged through sustainability initiatives to bring about more equity and empowerment. “We documented a lot of initiatives led by women,” said Fabio de Castro, a co-principal investigator in the project and a senior lecturer at the University of Amsterdam’s Center for Latin American Studies, “and we observed how some communities have been able to reshape their narratives around sustainability in the context of social inclusion – so it’s not only about the environment, but it’s about making the process sustainable in a broader sense.”

Photo: piccaya.

The research process itself – which was participatory from the outset – provided an important learning opportunity for all involved, said Brondizio. “The collaborations with our partners on the ground became very strong through each stage of the process,” he said. “The whole [research] team focused on working together with stakeholders from the beginning to generate products that were of interest to them – not only academic interests.” This included learning to adapt language and mindsets to cultivate common understandings: a journey that required both time and humility, as de Castro said.

He also drew attention to the transformative impact of the process. “The agency of people on the ground certainly became stronger,” de Castro said. “And from our side, as researchers, we’ve been transformed in this process. We’ve learned a lot about how to interact and how to acknowledge this co-production of scientific and technical knowledge with local knowledge that was already there, to make this bridge between the two kinds of research.”

Brondizio said the project also made valuable developments in terms of finding ways to connect place-based initiatives with wider regional transformations. “It’s quite challenging to show how people’s action and decisions on the ground have implications for a much larger landscape,” he said. “Developing those mechanisms, in connecting different kinds of community participatory work, such as the expansion of agroforestry production systems with satellite remote sensing and other tools, represents an important methodological advance.”

The project was not without its challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic being the most significant. The majority of the planned in-person work had to be cancelled during the project’s second year, and the collaborators had to find new ways to work with each other. Fortunately, the team had already built strong relationships during fieldwork in 2019 and were able to pivot from there to running online ‘dialogue workshops’ with different groups of communities, particularly in Peru; an effort led by co-PI Krister Andersson and doctoral student Adriana Molina Garzon (University of Colorado). However, Brondizio said “it was a big challenge to maintain some of the initial goals of the project,” for several reasons. Many participants had internet access and connectivity challenges, and the “energy of being in the same room”, as De Castro called it, was of course lacking.

Perhaps more saliently, though, most communities faced difficult personal, political, and economic situations during that period, “so they had their attention somewhere else, in that they were in survivor mode, focusing on their health and livelihoods,” said De Castro. This context also highlighted the ‘fine line’ that participatory researchers often navigate, where they are intimately involved with communities “and trying to bring their voices to a larger audience,” said Brondizio, “but at the same time the research team is limited in terms of the interventions we can make on the ground.”

Looking ahead, the team is working to gather more political, public and media attention for the initiatives, and to pursue a new strand of the project called ‘Linkages’, which is focused on how Indigenous and local knowledge can serve the development of an inclusive bioeconomy for forest and agroforestry products, and floodplain fisheries in the Amazon. In the bigger picture, the collaborative project also includes producers, associations, and cooperatives working together to understand how to overcome barriers and promote value-aggregation close to producers, generating income, employment, and supporting multifunctional landscapes for a vibrant, sustainable future – particularly for local young people like Gabriel.

Photo: Matthew Williams-Ellis