This article is part of the series ‘Women Scientists Around the World: Strategies for Gender Equality,’ which explores the drivers and barriers to gender representation in scientific organizations. It draws on a qualitative pilot study I conducted in consultation with the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES), based on interviews with women scientists from various disciplines and geographic regions. The series of articles are published simultaneously on the websites of ISC and SCGES.

Born in Iran, Encieh Erfani pursued her passion for cosmology with distinction, obtaining her Ph.D. from the University of Bonn in 2012 with a dissertation on “Inflation and Dark Matter Primordial Black Holes.” Her academic career has since spanned across continents, from research positions in Italy and Brazil to her long-standing role as an assistant professor at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences in Zanjan, Iran. Since 2015, she has been recognized as an active contributor to her field, with numerous publications and invitations to participate in international conferences and collaborations.

However, Dr. Erfani’s career took a significant turn in 2022, driven by events unfolding in her home country. During a research visit to the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Cuernavaca under the World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) Fellowship, she resigned from her academic position in Iran.

This decision stemmed from the eruption of protests after the death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman who died in custody after being detained for allegedly violating Iran’s compulsory hijab law. “I felt a profound anger,” Erfani explains, “and decided that I could not continue like this.” For Erfani, it became morally impossible to maintain an official affiliation with a regime where women were being killed over compulsory dress codes.

Since then, her subsequent temporary appointment at the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, provided some respite, and in 2023, she secured a temporary research position at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany. As an exiled scholar, her safety depends on securing employment opportunities abroad.

Dr. Erfani was the first Iranian academic to resign in direct response to these events. Despite the lack of any guarantee of immediate employment or financial security, she did not hesitate to personally stand against what she describes as a system of “gender apartheid.”

Several international organizations are advocating for the legal recognition of gender apartheid; defined as the institutionalized system of domination and oppression based on gender. Notably, an international campaign “End gender apartheid” is working to update apartheid standards in international law to include “gender hierarchies, not just racial hierarchies.”

The concept, as explained by Amnesty International, was first articulated “by Afghan women human rights defenders and feminist allies in response to the subjugation of women and girls and systematic attacks on their rights under the Taliban in the 1990s”. The notion of gender apartheid is regaining momentum, with the Taliban’s’ return in 2021, and the protests in Iran. Following the situation in Afghanistan, experts from the UN Working Group on discrimination against women and girls are advocating for gender apartheid to be recognized as ‘crime against humanity’.

Throughout her academic career, Erfani has been a fierce advocate for gender equality. She highlights the systemic discrimination faced by women in Iran, Afghanistan, and other regions, where gender-based laws and practices severely restrict women’s participation in public life. The situation in Iran, where girls are expected to wear the hijab from as young as nine, is particularly emblematic of the constraints placed on women. For Dr. Erfani, this goes beyond dress codes—it represents a broader system that denies women their basic human rights, from access to education to employment and to overall participation in society. “If you don’t wear the hijab, you will not be able to go to school,” she explains. “If you don’t wear it, you do not have your human rights as a woman, you are not able to study, to get a job”.

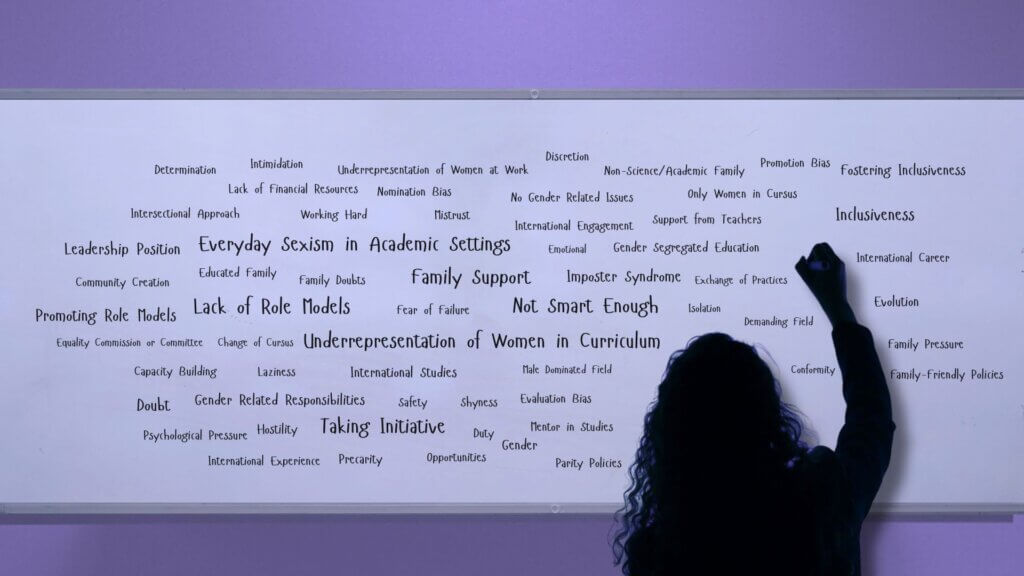

One of Dr. Erfani’s long-standing goals is to promote the inclusion of women in science, particularly in astronomy. She was the first woman elected to the Board of Directors of the Iranian Astronomy Society and worked to establish a female branch within the organization. This initiative was intended to create a safe space for women interested in astronomy, particularly for those involved in amateur sky observation, an activity that requires being out during the night, gazing at stars. Many families, particularly in conservative settings, would not allow their daughters to participate in such activities, viewing them as inappropriate. Erfani then proposed creating observation spaces in national parks, offering a secure environment for young women to engage in astronomy. However, her efforts faced resistance from colleagues, who questioned the need for a separate women’s branch.

Despite these obstacles, Erfani remains committed to her cause. “I have many female friends who are excellent astronomy photographers and teachers,” she says, “and I wanted to make them visible.” While she found support among amateur female astronomers, gaining the backing of her academic colleagues proved more difficult. Many feared that associating with gender equality initiatives would label them as feminists, which carries its own social and professional risks in Iran.

According to Dr. Erfani, in this gender apartheid context, universities play a crucial role to give women a chance in Iran. As boys and girls and are segregated throughout their education, “this means that until the age of 18, your chance to socialize with men is very limited”. Attending university, which is only possible after passing a competitive entrance exam, offers women in Iran an opportunity to access a different social reality and expand their world. Many choose universities far from their hometowns to gain freedom from family traditions. As a result, the gender ratio at the undergraduate level is evenly split, with women making up 50% of students. However, fewer women pursue engineering, as men are often drawn to fields with better job prospects. In contrast, the percentage of women in physics is notably higher than in Western countries. “There is no other way for women to lead a normal life,” Erfani explains. “The only path available to them is through universities; for many, education represents freedom from evil.”

However, at the Master’s and particularly Ph.D. levels, the number of female students drops significantly, with women comprising just 30% or fewer of Ph.D. candidates. The situation is even more pronounced among faculties, where women are predominantly found at the assistant professor level, as the recruitment of female faculty has only recently begun. “With the growing number of women earning Ph.Ds, they can no longer be ignored. However, there is still resistance” she adds.

Dr. Erfani observed discrimination against women in her physics department. For example, during a meeting, a faculty member explicitly stated that he would not teach computer coding for physicists to female students because they “are not good at computing,” and suggested that “another lecturer should teach the female students.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was opportunity of an online workshop about “equity, diversity, and inclusion” (EDI) organized with the American Physical Society. The only requirement for the workshop to happen was to have twenty participants — five faculty members and fifteen students. Finding faculty members proved challenging. “I couldn’t find four faculty members to join me in writing a proposal for the gender equality workshop, and the head of the department didn’t provide a support letter. People are scared to talk about gender equality, even for an online workshop!” Nevertheless, students, both men and women, showed great interest in the issue of gender equality, and many wanted to participate.

Dr. Erfani left Iran before the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, which followed the death of Masha Amini. The movement generated severe repression in the country, including in universities. “Female students must now strictly obey the compulsory hijab rules, which are much more restrictive than before. There are checkpoints and cameras at university, and if they don’t follow the dress code, they aren’t allowed to attend classes.” Dr. Erfani explains that many students received threats, warning that if they do not comply, they will lose access to university services like dormitories, libraries, theaters, and public spaces. Others have lost their right to education entirely for not adhering to the rules. “It’s been more than two years since I left Iran, so I can’t fully describe the current atmosphere or how male students are supporting female students. But from what I see, the younger generation of men seems more supportive of women.”

Dr. Encieh Erfani was an Assistant Professor of Physics at the IASBS, Iran. She resigned on 23 Sep. 2022 due to the events in Iran. She obtained her Ph.D. from Bonn University, Germany (2012). Her research area is theoretical physics with a concentration on cosmology.

blog

blog

blog

blog

Science in Times of Crisis is an ISC-led collaborative project which mobilizes Members and other ISC partners to respond to support colleagues affected by crises around the world, including Ukraine, Gaza and Afghanistan.

Protecting science in times of crisis

This working paper addresses the urgent need for a new and proactive approach to safeguard science and its practitioners during global crises.

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in our guest blogs are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council