On 23 May 2022, it started raining heavily in the metropolitan area of Recife, the capital of Brazil’s northeastern state of Pernambuco. In fact, it was a deluge. More than 150 mm of rain fell within 24 hours. Two young citizen scientists in the neighbouring city of Jaboatão dos Guararapes began measuring the rainfall in rain gauges they had built and then entered that data into an app on their smartphone.

The citizen scientists studied the data in the app and applied what they had learned about potential flooding. They immediately sent out an alert to their community: Area with flooding, due to the increase in millimetres of rain. Alert situation. The community mobilized and headed for safer ground.

The flash floods and landslides of May 2022 in Pernambuco killed 133 people and displaced 25,000. Jaboatão dos Guararapes was the most impacted city with a death toll of 100. People in the neighbourhood of the two citizen scientists lost their homes, but due to their early action of self-protection, no one lost their life.

Almost one quarter of the world’s population is directly exposed to significant flood risk. But the impacts of extreme weather and flood risks are not felt equally across the world. They can be particularly devastating in more physically and socially vulnerable areas, such as poor neighbourhoods in Brazil and in the Global South.

‘We need to increase our capacity to cope with flood risks and make our communities more resilient to extreme weather events,’ said João Porto de Albuquerque, a professor in urban analytics at the University of Glasgow, UK. ‘And we need to focus on the poor and people living in vulnerable situations.’

As part of the Belmont Forum, NORFACE network and the International Science Council research programme Transformations to Sustainability (T2S) the Waterproofing Data: Engaging stakeholders in sustainable flood risk governance for urban resilience project explored how to build the resilience of communities to flooding by focusing on social and cultural aspects of data collection and management.

Waterproofing Data was conducted by an international team of researchers with multiple disciplinary backgrounds from Brazil, Germany and the United Kingdom, in close partnership with researchers, stakeholders and local communities of a multi-site case study in Brazil.

The project engaged communities in the process of generating the data used to predict when floods will occur.

‘Better early-warning and effective community-based risk reduction programmes can save human lives and mitigate the significant economic impact of disasters,’ said João.

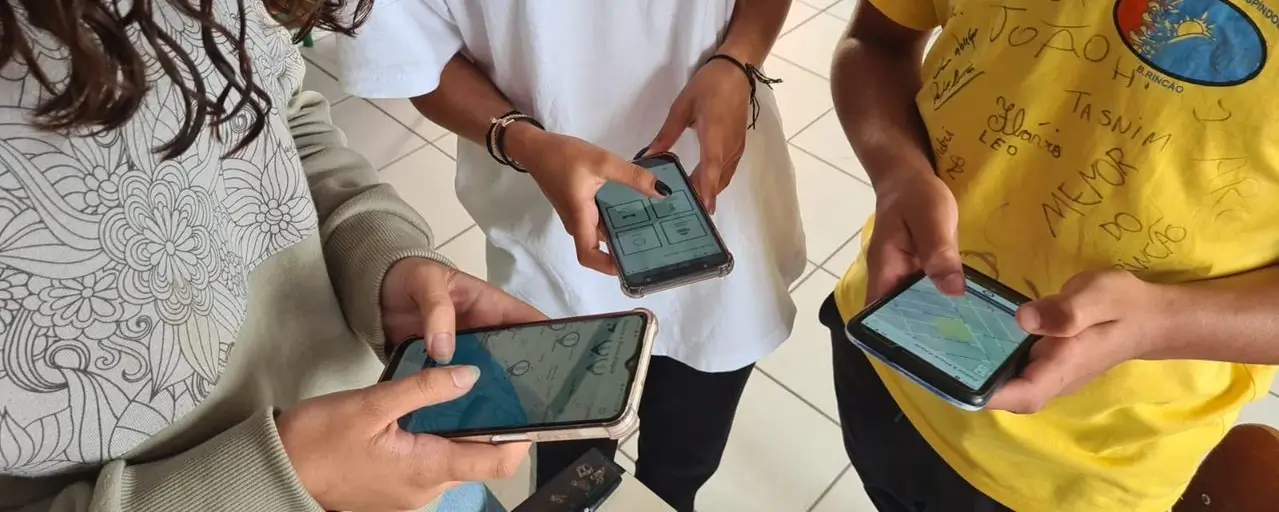

Photo: Waterproofing Data team, São Paulo

Impoverished neighbourhoods are most vulnerable to natural hazards and other climate change impacts due to rapid urbanization, their location in flood-prone areas, and a lack of durable housing, water and sanitation infrastructure, or natural drainage. In many cities of Brazil, rapid urbanization has resulted in the expansion of deprived neighbourhoods, called ‘favelas’ or slums.

Data about the risks and impacts of flooding and other natural hazards are often missing from these neighbourhoods. ‘Creating detailed data about a country as huge as Brazil is a tremendous challenge,’ said Maria Alexandra Cunha, a co-investigator on the team and a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation. ‘Social inequality is frequently associated with data inequality, and this is evident with the data gaps in impoverished, marginal urban areas.’

With insufficient data about rainfall and flooding in an area and very little data about the physical and social characteristics of these neighbourhoods, it is very hard to predict when floods may occur and what impact they might have. ‘This increases the risk to these communities as they are less likely to have any warning before floods,’ said Maria.

The project aimed to explore how to build the resilience of communities to flooding by helping them generate the data used to predict when floods will occur. To do that João and his colleagues turned to ‘gardening.’

‘Inspired by the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, we proposed that by learning how to read and write digital data, citizen scientists could become active agents in improving the resilience of their communities,’ explained João. ‘This required a shift from seeing citizen science only as a “data gathering” activity to empowering citizens as knowledge co-producers in a process we call “data gardening”,’ said João.

The gardening metaphor signals a shift from seeing the data generation process as a mere means to an end, to emphasizing the need to nurture and cultivate social processes which not only generate data but also empower participants to transformative social learning.

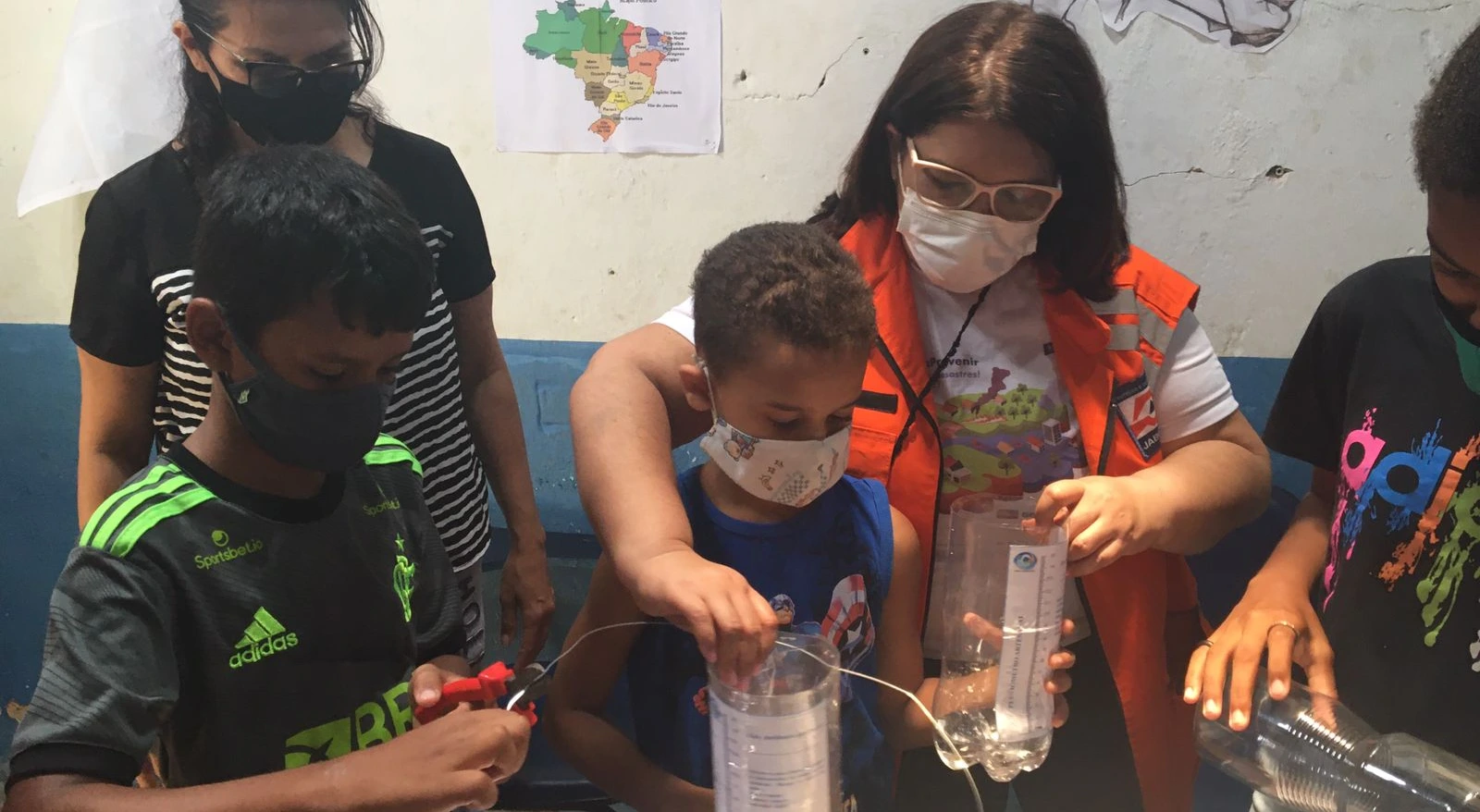

Photo: Civil Defence and Protection Agency of Jaboatão dos Guararapes, 2021

The project’s approach focused on moving away from a top-down process of dissemination and instead looked at a process of ‘pollination.’ ‘We engaged local facilitators in schools and municipal civil defences who became ‘the pollinators’ who helped us to spread the seeds we cultivated in our data gardens,’ said Rachel Trajber, a researcher at Brazil’s National Centre for Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning (CEMADEN).

The project seconded 15 schoolteachers and six civil protection agents to act as pollinators in nine cities in five Brazilian states.

The Waterproofing team developed a school curriculum about flooding which supported teachers in adopting an integrated critical teaching approach. ‘In the curriculum, students learn concepts about science, flooding risk, vulnerability and resilience,’ said Rachel. ‘They then act as “citizen scientists” by generating and analysing data about their own neighbourhoods.’

Students learned how to construct rain gauges from plastic bottles and installed them close to their homes so they could create an observation network. They then recorded the data in an app that the project developed and share their rainfall measurements with Brazil’s national agency for flood early-warning, CEMADEN. They also recorded flood events in the app and their impacts on the neighbourhood. Students also learned about open digital mapping tools and participatory mapping of risk perceptions using open digital mapping tools such as OpenStreetMap.

‘The app and curriculum enabled the communities involved to democratize flood data, raise awareness of flood risks, and co-design new initiatives to reduce the risk of disasters to communities,’ said Rachel.

The Waterproofing Data project engaged more than 300 school students and community members and gathered sound evidence about the positive impact for the communities involved in data generation. The project demonstrated that citizen science programmes that connect school students and local civil protection agencies can be an effective means to co-produce data innovations for disaster risk reduction.

Photo: Civil Defence and Protection Agency of Jaboatão dos Guararapes, 2021

‘We found that engaging school students with citizen science projects to map their local communities, monitor rainfall levels and record flood impacts helped young people to understand flooding risks and increased their awareness of how climate-related hazards affect their neighbourhoods,’ said João. ‘And at the same time, the students are generating valuable data for flood risk management agencies.’

The Waterproofing Data project has already had significant impacts on flood-prone communities, and its efforts have been recognized as it was shortlisted for the Times Higher Education Awards 2022 Research Project of the Year in Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences.

João believes this citizen scientist approach could help empower communities across the world to prepare and defend themselves for much more than floods and be used against many impacts of climate change such other weather events. ‘While this research was conducted in Brazil, the lessons learned about engaging citizens in data gardening could be applied to empower community-led climate action in other regions across the world, especially in areas with significant physical or social vulnerability,’ said João.

Header photo: Rosinei da Silveira, Balneário Rincão