This blog forms part of a series for the ISC on plastic pollution and the Second Session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution.

Plastic pollution has become a global environmental issue, reaching even the most pristine and remote parts of our planet, including Antarctica and the surrounding Southern Ocean. Antarctica is one of the last remaining wildernesses on the planet. It is largely unexplored and has few inhabitants but is under increasing pressure from the human footprint. The Southern Ocean comprises around 10% of the global ocean. It is of critical importance to the equilibrium of the Earth system and exhibits distinctive and exceptional marine biodiversity, but it is now under threat from plastic pollution.

Plastic pollution in Antarctica occurs almost everywhere, from open ocean to coastal environments, contaminating the water, sea ice and sediments around the continent and surrounding sub-Antarctic Islands. Entanglement of marine mammals and birds and ingestion of plastics by marine predators including fish, mammals, and birds, along with increasing numbers of reports of microplastics found in animals living on the seabed and in terrestrial food webs, are clear evidence of the extent of plastic pollution and a cause for serious concern.

The impact of plastic pollution is affecting the resilience of Southern Ocean ecosystems and jeopardizing a delicate balance that has evolved over 40 million years. While significant advancement and scientific progress has been made in the monitoring and assessment of plastic pollution in other regions of our planet, little is known in Antarctica despite the urgency of the issue. Plastic pollution is clearly a global concern, however the remoteness and difficulty of access to Antarctica make it difficult to investigate and quantify consequences on the unique Antarctic terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Southern Ocean biodiversity and ecosystems are now more vulnerable than ever before, due to recent rapid environmental changes, including climate warming and ocean acidification. Thus, the unique ability of Antarctic organisms to adapt to extreme conditions is already threatened by changes to our climate. Many of these species have narrow tolerance ranges and they are facing an additional threat from plastic pollution. Antarctic marine animals are becoming increasingly exposed to the combined presence of plastic pollution and human-induced climate change. Addressing the potential impact of plastic pollution in isolation does not allow us to fully predict consequences in years to come. It is critical to account for potential cumulative effects with other stressors. The interactions between climate change and micro- and nanoplastics are likely to magnify the potential for interactions with other toxicants, as well as lead to an enhanced susceptibility of Antarctic species to these stressors.

Understanding the sources of plastics entering from within and outside the Southern Ocean and quantifying the scale of the problem are essential to minimize any environmental threat to the unique biodiversity and ecosystems of the region. Plastic found in the Southern Ocean is likely to have originated from both local and global sources, with new evidence that some items may have entered the ocean at lower latitudes, crossing perceived oceanographic barriers to reach Antarctic coasts. Furthermore, Southern Ocean ecosystems are inextricably connected to global ocean ecosystems and are an important part of many Earth system processes. Therefore, the impact of plastic pollution on Southern Ocean ecosystems should not be considered in isolation but set in a global context.

The challenges associated with scientific research in polar regions require a common set of actions and strategies to ensure consistent and replicable data collection. It is important to establish standard procedures for plastic pollution monitoring and impact assessment and to increase data coverage both spatially and temporally. This will require a combined effort from all stakeholders operating in the Southern Ocean and in adjacent regions, and a global conversation examining tailored and immediate actions to prevent any detrimental impact on Southern Ocean integrity and resilience within the broader perspective of the global ocean. Marine and terrestrial plastics in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica represent a serious concern and we need to act now before it is too late.

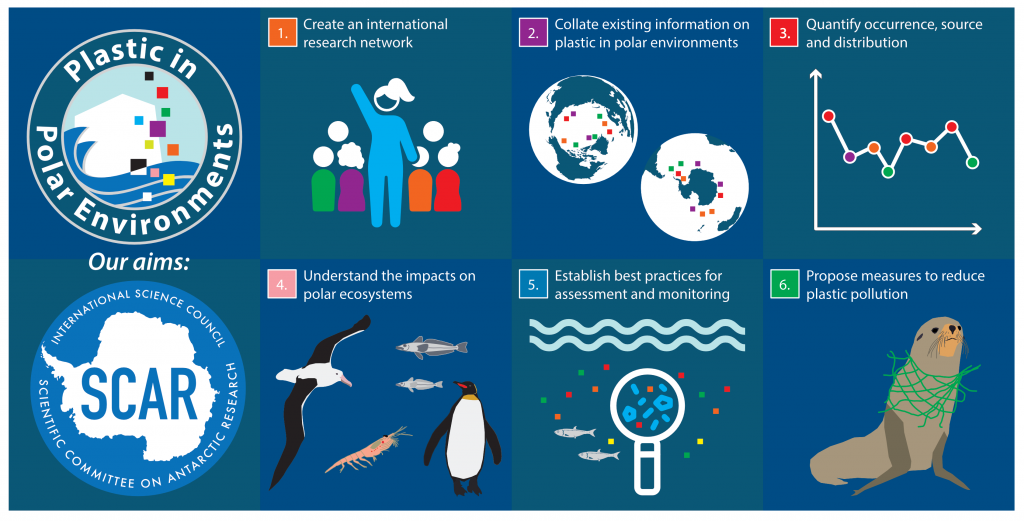

Sources of plastic must be identified to manage their entry into the Antarctic marine and terrestrial environments; local and global initiatives are urgently needed to prevent further plastics reaching the Southern Ocean and Antarctica and to clean up the existing problem. The Plastic in Polar Environments Action Group (PLASTIC-AG) of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) is promoting the importance of commitment of major organizations operating in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica to build common frameworks and strategies for managing plastic waste.

The PLASTIC-AG was established by SCAR in June 2018 to connect researchers from around the globe with an interest in plastic pollution in Polar regions. The key aims of the Plastic-AG are to collate information, establish baselines, understand the impacts of plastic pollution, establish standardized procedures for sampling and monitoring, and propose new measures to reduce and/or limit any potential negative impacts on Polar Environments.

Image by Claire Waluda, British Antarctic Survey