Scientists and researchers increasingly value science fiction for its contributions to anticipating future scenarios. As part of its mission to explore the directions in which changes in science and science systems are leading us, the Centre for Science Futures sat down with six leading science fiction authors to gather their perspectives on how science can meet the many societal challenges we will face in the next decades. The podcast is in partnership with Nature.

In this inaugural episode, the Centre engaged with Kim Stanley Robinson, a New York Times bestselling author and recipient of the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards, to explore the potential of science fiction in guiding scientists and policymakers toward innovative and beneficial futures. What valuable lessons can science fiction offer to scientists about their profession?

Tune in to this episode to discover more about Robinson’s view of science as a political and an ethical project.

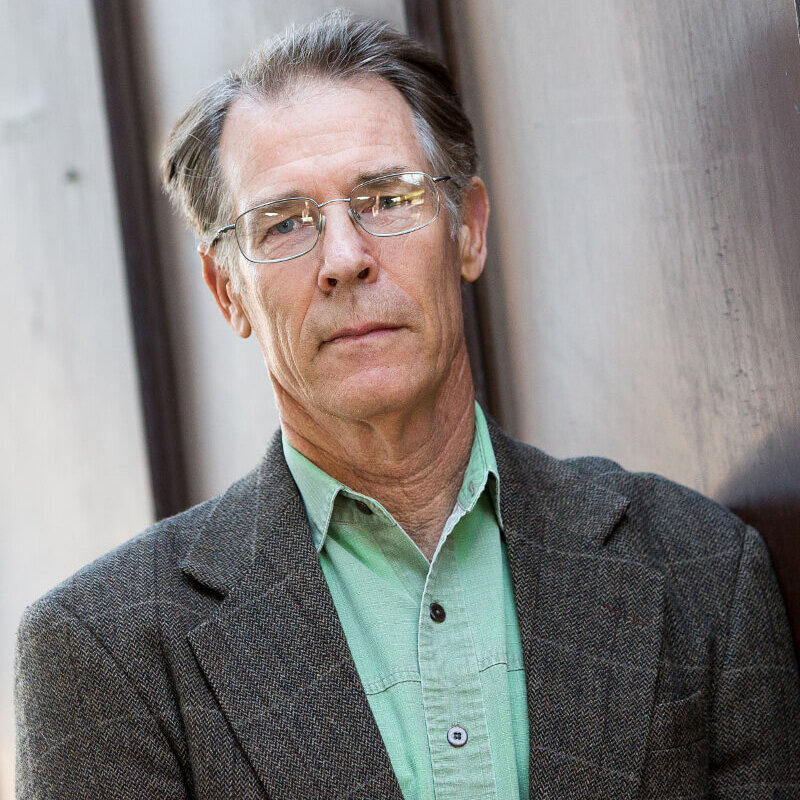

Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson, author of over twenty books including the bestselling Mars trilogy, New York 2140, and The Ministry for the Future, was recognized as a ‘Hero of the Environment’ by Time magazine in 2008. He is actively involved with the Sierra Nevada Research Institute (SNRI) and resides in Davis, California.

Paul Shrivastava (00:04):

I’ve always had a love of science fiction, and in the last few years I found myself returning to it as part of my professional research work because of the profound and powerful ways I believe it can shape our thinking about the future. I’m Paul Shrivastava, and in this podcast series I will be speaking to science fiction authors from around the world to get their perspective on how science can meet the many challenges we face in the coming decades, from climate change and food security to the disruption caused by artificial intelligence. I wanted to speak to leading science fiction writers in addition to scientists because they can offer us a unique perspective on these issues. They are, after all, professional futurists.

Kim Stanley Robinson (00:58):

Science fiction hit me like a gong, like I was the gong and I had been hit and I was ringing.

Paul Shrivastava (01:05):

In this first episode, I spoke with Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the foremost science fiction authors in the world. Over the past four decades, he’s written many books, including my favorite, The Ministry for the Future, which is unique in giving hope to the challenge of climate change. He’s also covered many themes like human settlements and space in his Mars trilogy and AI powered quantum computers in the novel 2312, and has won pretty much every science fiction award going, sometimes more than once. Stanley has inspired generations of science fiction readers and writers. Our conversation touched on many topics including the dangers of escapism, climate grief, and the myth of scientific objectivity. I hope you will enjoy it.

Paul Shrivastava (02:04):

Stanley, I want to begin with what got you interested in science, your personal connection to science.

Kim Stanley Robinson (02:10):

When I ran into science fiction, I was an undergraduate at UC, San Diego. I thought this is the realism of our time. This describes how life feels better than anything else I had read. So I began to get story ideas by reading general science magazines. You could take randomly any two articles out of science news, combine their implications together, you have a science fiction story. Then I married a scientist. I got to see a working scientist at work, and then I myself was accepted into a program run by the National Science Foundation. So I got to see how NSF works as a grant giving organization, and the NSF sent me to Antarctica twice. I got interested in climate science because a lot of the scientists down there were working on it. And now this is, I don’t know, it’s about 20 years of consistent effort on what you might call climate fiction.

Paul Shrivastava (03:07):

Working with NSF, that is a very interesting part because very few people get an inside look at how grants making actually works. Here I want to begin by pointing out something that I just finished reading, a book by Douglas Rushkoff called Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of Tech Billionaires. And all they were interested in asking him was, “How do we escape the Earth?” And it made me think the possibilities of escapism are seeded into our minds by science fiction, maybe?

Kim Stanley Robinson (03:43):

I think it is, and I myself am heavily implicated in this because my Mars trilogy is by far the longest, most scientifically plausible scenario for humanity turning Mars into a “second home.” That novel, while I regarded as a good novel is not a good plan. I wrote it in the early nineties before we learned that the surface of Mars is highly toxic to humans. As an escape hatch for now, for tech billionaires or anyone else, it’s useless. A lot of this escapism is done as a fantasy in that there’s a part of those people that knows perfectly well that it won’t work, but they want a sense that if push came to shove and if the world civilization fell apart, they could somehow dodge that.

Paul Shrivastava (04:38):

You’re absolutely right. And it brings me to this question. Are there lessons for policymakers that can be drawn from science fiction?

Kim Stanley Robinson (04:47):

To have science fiction be actually useful to policymakers, they would have to read some science fiction. But it would be best if it were curated by somebody that knows the field and can send them to good works of science fiction. And there’s a lot of useless science fiction out there, repetitive, foolish, dystopian, et cetera. Sometimes a dystopia can say to you, you don’t want to do this, but you don’t need much of that before. What you really need is interesting and engaging utopian fiction or people coping with damage successfully. People are given a sense of hope that even if there isn’t a good plan, we might come to a good result anyway.

Paul Shrivastava (05:34):

Yeah, I have been recommending that people read The Ministry for the Future. I’m asking scientists to read it because it really does open their minds to the positives. But how do we take the message, the positive message, the hopeful message that you’re casting to the masses?

Kim Stanley Robinson (05:53):

It’s easy to imagine things going wrong since it’s so remarkable that it’s going even as well as it is. And in fiction in general, a plot is the story of something going wrong. So there’s a gravitation, there’s a tendency for fiction itself to focus on things going wrong so that plots can be generated. Now the further elaboration of the plot is the characters coping with what’s gone wrong and hopefully fixing it. And then if there is a powerful strand of utopian science fiction out there, then the future will begin to seem contested and not preordained to catastrophe. And scientists need to help on this front of saying to the world, you are alive because of science.

Paul Shrivastava (06:45):

Yeah, that’s true. I think the scientific community has a responsibility. But at the same time, I think science itself is not a uniformly good and beneficial-to-all sort of activity, right?

Kim Stanley Robinson (07:01):

Yes, this is a great line to pursue. And thank you, Paul. Science is a human institution. It’s not magic, and it’s not perfect, but it is improvable. And as a methodology, it is interested in improving its methods. So it has a self-improvement, recursive element in the history of science. And you can see times where it went wrong. Since science allowed the allied powers to win World War II by way of radar, penicillin and the atom bomb, in the post-war period, people regarded scientists as if they were magic priests. High priests of some mysterious power, mostly men, white coats, incomprehensible. And yet, they could actually blow up your city. There was a moment of arrogance of hubris in the scientific community itself. And it has been working since then to comprehend what happened and to do better. A sense of care in the sciences has been growing, and it’s institutionalized. In other words, science is an attempt to make a better society, perhaps less monetary, less grasping.

Right now, in the midst of our ordinarily grasping in capitalist world, science is a counterforce. So to the extent that scientists are politically self-aware, they would do a better job because there’s many of scientists that say, “Look, I got into science so that I don’t have to think about politics. I just want to pursue my studies.” And yet they are inevitably enmeshed in a political world.

Paul Shrivastava (08:43):

So what message would you bring to the scientific community for engagement, for taking responsibility?

Kim Stanley Robinson (08:51):

Well, I have thought about it a lot, because there’s only so many hours in the day. And doing science itself. How can you possibly do more in terms of communicating to the public, et cetera? Well, you can give some time as an individual scientist to representing science in the schools, from the youngest levels right on up through college. But more importantly, every scientist belongs to scientific organizations. And there, the power of the collective is important. I think some group actions like linking elbows with other organizations, maybe inserting themselves into the political process. So, phrases, public relations methods to get the message out there. A better job could be done for sure.

Paul Shrivastava (09:39):

I think scientists have the self-perception of their profession where we center objectivity and we systematically remove subjectivity and values.

Kim Stanley Robinson (09:51):

Well, this is a good point, Paul, because there is that myth of objectivity that science is pure and it’s only studying the natural world. We need what John Muir called the passionate scientists, that the science is being done for a purpose, which is human betterment or the betterment of the biosphere at large. But if science began to understand itself as a religious act, that the world is sacred, that people should suffer as little as possible, given our mortality and our tendency to fall apart, it’s a pursuit that has a point. It’s not just the objective work in the lab to see which molecule is interacting in which way. It’s always also a political project and an ethical project.

Paul Shrivastava (10:38):

Being a passionate scientist is important. But the structures, the administrative structures, the NSF rules for granting money, the reward systems within academia, tenure promotion, publication…, these professional structures and processes militate against allowing that to happen. What might be some ways to overcome these structural barriers now that science is riven with?

Kim Stanley Robinson (11:08):

Well, sometimes the structures of sciences are actually encouraging voluntary work for the good of other people: the peer review process, the editing of journals for free, the entirety of the way that the scientific institutions as they’re now set up. One of the things that you need to do is calculate where to give the volunteer time that you’re expected to give to create the social credit, to get the job advancements that you want, in order to do the lab work that you want. So even if your curiosity is entirely on your subject alone, you nevertheless have to help other scientists along the way, in order to create that space for yourself to do your own work. In other words, it’s already way better than most of society in the way that it’s structured. So that although science obviously always has room for improvement in its methodologies, if the rest of the world were behaving more scientifically, we would be way better off. So it’s an interesting question. How do you make your own field better when it is already probably the best social organization we have on the planet? But how do you then also make the rest of the world see that, understand that and become more like you? Well, this is again the problem of the leadership, the avant-garde. It shouldn’t be up to a small group that everybody has to be on board. These are political problems that need to be constantly discussed.

Paul Shrivastava (12:38):

And I think universities as the sort of place, where a lot of science happens, need to rethink their own role. Because these universities set the parameters for promotion, tenure and all of these other things, according to which scientists behave later. And at least currently, when I look at the world’s leading universities, I don’t see them reacting with the sense of urgency.

Kim Stanley Robinson (13:05):

Yes, and the university—this is a great topic for discussion—is a battlefield. The university is the side of the battle for control of society between science and capitalism. And universities are run by administrative units that are very often not scientific bodies, but rather administrative units staffed by people who came out of business schools. And university is being seen as a real estate developer and a place to make a lot of money. If a university just says, “Well, it’s only our job to make more money,” rather than “making more knowledge and making a better world,” then really, we’ve lost one of the major forces for good in the world.

Paul Shrivastava (13:44):

Money can be redirected. Business models can be changed. It is not a foregone conclusion that we will continue in this path, so that’s a hopeful thing. I want to bring a similar kind of model from another domain, which I know you are interested in. And that is permaculture.

Kim Stanley Robinson (14:01):

Ah, yeah.

Paul Shrivastava (14:02):

So I want you to say some things about what you find interesting and what its potential is in the coming Anthropocene era.

Kim Stanley Robinson (14:10):

Well, I’m glad that you asked, because I’ve been interested in permaculture for a long time, which is really, we could now call it sustainable agriculture. In the Anthropocene, humanity needs food and a lot of it. At the same time, we need to draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to stabilize our climate. If those two could be combined into the same process, this would be a gigantic achievement. Permaculture is a historical footnote from the 1970s. But it’s a precursor to what we are now calling regenerative agriculture.

Now, I live in Davis, California. So a big university like UC Davis and all of the big ag universities around the world, they’re getting money from agricultural corporations to keep doing Green Revolution type work. The methodologies used were fossil fuel and pesticide heavy. They got results. There was more food. But it isn’t truly sustainable over the long haul. And this is a problem because the big ag corporations, they’re interested in profit in the immediate present, not in long-term sustainability. Government ought to be pushing them around, setting guardrails, setting incentives, setting penalties, setting positive incentives of rewards for doing sustainable ag and regenerative ag, as fast as possible. In essence, we need to take command of a technology that we’ve developed and not use it to make profit in the present, but use it to make sustainability for the long haul.

Paul Shrivastava (15:47):

What are we trying to do in sustainable agriculture or permaculture that is not necessarily technological intensity?

Kim Stanley Robinson (15:55):

There’s an old Buddhist saying: “If you do good things, does it matter why you did them?” And then from above and everywhere, I think has to seep through what’s being called the sustainability imperative. That more important than making money or increasing efficiency, which is a very dubious value, more important is survivability over the long haul for the generations to come. That’s a general attitude that then infuses the detail work. How you make that change? I guess you just keep talking about it and pointing out that some things are not open for discussion. We do have to quickly invent and institute new technologies or bring back old ones that make a better fit with the biosphere and don’t destroy it.

Paul Shrivastava (16:46):

One more question, which just occurred to me that this was still lingering from reading The Ministry for the Future. One of the things that turns that book into a really profound document is the way violence nudges action. And so my question is, in the real world, is there a role for climate action if we have only 10 years or 20 years to act? Is there a role for violence as depicted in your science fiction and in several others?

Kim Stanley Robinson (17:23):

No, I want to say no to this. Ministry for the Future is a novel, not a plan. And it wants to imitate the chaos of the next 30 years so that you can believe a good outcome is possible despite the chaos. I had to include the violence because there’s going to be violence. But it probably won’t be useful. The real use will be done in the labs, and in the boarding rooms and the various places where power changes laws. And the violence, if it’s happening, will often work entirely against the wishes of those who do the violence. If you then talk about active resistance to the fossil fuel industries wrecking the world and their various minions, then that act of resistance can take many, many forms that have not been fully articulated or tested. But I hope we see a lot of them in terms of civil disobedience and non-compliance, maybe even sabotage of objects. Yes, if we’re going to get our act together fast enough, it could be that some people in power should be more scared than they are. And some profit columns should drop into lost columns and become uninsurable because of damage to property that they can’t prevent.

Paul Shrivastava (18:44):

So I’m hoping that more and more books like yours will become available, made required reading. If you have any parting thoughts about how we might bring about that integration of the sciences and the arts,

Kim Stanley Robinson (18:59):

All scientists as part of their training should be required to take courses that teach what science is. The vast field of science studies that the humanities and social sciences have brought to bear on how sciences work, the self-reflection on what they’re doing is never a bad thing. They should not be left naive philosophically or politically at the end of a scientific education. That any department could do. Any university could do that and should do that. It would create a more flexible and powerful core of science workers to have that education. And so in terms of requirements, I think that should be done. A few science fiction novels included in that list, some philosophy of science. I mean, do people read Thomas Kuhn and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions? Well, I don’t know, but they certainly should to comprehend their own work.

Paul Shrivastava (20:00):

Thank you for listening to this podcast from the International Science Council’s Centre for Science Futures done in partnership with the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination at UC San Diego Visit futures.council.science to discover more work by the Centre for Science Futures. It focuses on emerging trends in science and research systems and provides options and tools to make better informed decisions.

Paul Shrivastava, Professor of Management and Organizations at Pennsylvania State University, hosted the podcast series. He specialises in the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. The podcast is also done in collaboration with the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination at the University of California, San Diego.

The project was overseen by Mathieu Denis and carried by Dong Liu, from the Centre for Science Futures, the ISC’s think tank.

Photo by Paulius Dragunas on Unsplash.

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in this article are those of the individual contributor/s, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council.