You have worked for many years on the interface of technology, power and society. Your most recent work, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, addresses the key challenges posed by digital technologies to our humanity. You are also a social psychologist with a long trajectory of working in interdisciplinary research teams. With this background in mind, how should we be rethinking human development today? What are the key challenges? What are the hopes?

The concept of human development is a modern psychological concept, but the phenomenon of human development is not purely modern. There is a long arc and a more contemporary arc. It is a phenomenon that has developed over millennia, because human development happens within the conditions of existence that occur in history. In terms of this big arc, human development has moved towards a meta-process of individualization over millennia. If we think about the history of mentalities and of human sensibility, the notion of the individual as a psychological entity has been extruded, drawn out with great difficulty and sacrifice, over many centuries and millennia. This larger arc of millennia constitutes a long process of differentiation and the construction of the self. It has produced the psychological individuals that we think about today when we speak of human development.

This new individual is marked by the construction of inner life as a legitimate realm that – ultimately, in the history of the emergence of the individual inner life – takes on not only a legitimate position, but an urgency and authority that in some ways supersedes social and collective life. The psychological individual is foundational for the very possibility and idea of democracy, let alone its practical construction – however imperfect. We cannot imagine a democratic society without imagining psychological individuals who have free will, autonomy, self-referencing capabilities to norms, values and rights, and who can conceive of situations where an inner reference to fundamental rights is stronger than the immediate demands of authority or of the collective.

The contemporary arc reflects the conditions of existence that we experience today, which now also challenge us to look beyond ourselves because of threats that require collective action based on attention to our shared humanity. We are challenged to bring the capabilities of individualization into a larger context, which really is the context of ‘us’. Today’s threats cannot be met solely with those cherished capabilities of autonomy, agency and the capacity for individualized judgment, self-reference and self-reflection. We don’t leave them behind, but we must integrate them into a larger felt space, and this will further differentiate our composition of what we consider ‘developed’.

The challenge now is moving from these miracles of individualization to a new frontier that is defined by the individual in relationship to the collective. Not through opposition, domination and subjugation, but rather through necessary solidarity. This is a new kind of sensibility. The climate crisis, for example, requires this shift. We cannot think of ourselves only as individuals, which is essential, but we also have to think as ‘one’, as a collective, as humanity, because there is no way of separating the threat to ourselves from the threat to us – it is one threat.

I regard the challenges of the digital century as analogous to the climate challenges: challenges to all of us and at the very same time challenges to each of us. When we talk about the threats of the digital century, we hear that privacy is a major one. Yet, privacy is a ‘catch phrase’. We are under the delusion that privacy is something private because we are thinking about this concept through the lens of individualization. This dilutes the meaning of privacy into some sort of private calculation, calculations that are exploited by the empires of surveillance capitalism.

For example, we think ‘I’ll give you this little bit of personal information – perhaps a photo I post on social media – in return for the “free” service of sharing my photo with friends and family and connecting’. In fact, privacy cannot be a private calculation in at least two ways: first, a society that cherishes privacy will always be fundamentally different from a society that it is indifferent to privacy. A surveilled society will never be the same as a society that prioritizes privacy as a right. They will be at variance in their respect for the dignity of the sovereign individual, the capacity for human autonomy, agency, free will and decision rights – all of the capacities essential to the democratic self. At the same time, every time we engage in these simple trade-offs of free services for a private advantage, we are captured by a lie. The surveillance capitalist empires have amassed unprecedented concentrations of information about us through systems designed to be hidden. Most of what they possess has been taken from us without our awareness. These data feed systems of artificial intelligence to discover patterns and predict future behaviour. The end result of this exchange has nothing to do with our presumed private calculation; it is information that is extracted from our experience without our knowledge and without our consent. It is, quite simply, surveillance. By choosing to participate in these unprecedented systems of knowledge and power, we unwittingly contribute to the large-scale monitoring and control of society.

For example, we innocently and willingly post our photos to Facebook and to other parts of the internet. Those photos are taken, without our knowledge and certainly without our permission, for example by Microsoft – a leading surveillance capitalist – for the largest data set in the world used to train facial recognition algorithms. When Microsoft created its ‘Microsoft Celeb’ training data set for facial recognition (it turned out that they were NOT merely taking celebrity faces), they said that it was only for academic research. But, in fact, the data set was sold to law enforcement agencies, companies and military operations including the military division of the Chinese Army that incarcerates members of the Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang. The whole province is essentially a surveillance mini-state. There are specific detention camps in Xinjiang where people are imprisoned by the ubiquitous presence of facial recognition systems that monitor them on a continuous basis on the street, in their homes and their workplaces, etc. These facial recognition systems are built on our faces, that we have freely given, under the delusion that privacy is private. No, it is not. Privacy is public – a collective good that can now only be preserved by collective will.

Here we have this very visible example of how thinking about this problem as if we are only individuals, with the capacity for judgment and decision rights to make a private trade-off, contributes to collective systems of tragedy and violence, control and injustice. This is why I link the challenges of the digital century to those of climate cataclysm. They are challenges that exceed our capacity as individuals to solve. They require us to integrate our hard-won capabilities as individuals into a larger framework of how we think, feel and act as members of a class called humanity. This is the positive challenge for humans all over the Earth. This is the new contest of human development.

The alternative to our engagement at this further frontier of human development is already present in the surveillance capitalists’ vision of our future. Their solution is to use systems of monitoring and control of populations to reconstruct society as a hive. This hive society is remotely tuned and controlled by psychological triggers, subliminal cues, engineered social comparison dynamics, real-time rewards and punishments and the pleasures of gamification. These are the tools that the tuners, those who administer the human hive, are inventing to redefine the social.

In this future we find that instead of society, it’s population; instead of individuals, it’s statistics; instead of democratic governance, it’s computational governance, where populations are tuned remotely based on behavioural data flows and their adherence to predetermined algorithmic parameters. This computational governance is imposed as the top-down solution to the emerging challenges of human development. What develops here are algorithms, not people. Computational governance is a replacement for the arduous challenging work of human development.

The politics of the hive are a feudal politics, a hierarchical politics of control, of one-way mirrors. They do not require violence, terror or murder, but they are, nevertheless, systems of unilateral control where the mechanisms of the black box are indecipherable. In this future, democracy becomes a distant memory, because there is no longer a need for participation, free will, autonomy, agency, decision rights or fundamental rights. There is, instead, the perfect confluence of the hive and the necessary metrics of efficiency and effectiveness as measured by, not only outcomes related to survival, but in the West – for now at least – outcomes related to profit and the profitability of the systems that are administered by the tuners, the feudal lords of algorithmic governance.

This is how I see the landscape and challenges of human development. These are the thoughts that are evoked by your questions inquiring about the meaning of human development today, the challenges and the way forward. If we are to meet these challenges, it is in that very meeting, in that very contest and struggle, that we surrender ourselves to precisely the kinds of experiences, processes and conflicts that are the motor of human development in the first place.

Human development happens not through observation but through participation; not just through harmony but through conflict; not just through stability and satisfaction but through instability, threat and problem-solving. These experiences compose human development. The pleasure principle alone requires no human development. Civilization is the product of sublimation – grief and contest, dissatisfaction and injury. In the same way, we only develop because we engage with challenges and contests. That is how over millennia we created the rule of law and charters of human rights to subdue violence. Engaging the conflict and driving it forward is how we advance human development.

Give us some concluding thoughts on what hopes you have to leverage these powerful digital technologies and the systems that create and operate them to do things differently and to get back to fundamental democratic values.

I have nothing but hope. The challenge of the next decade is how do we make the digital century compatible with democracy? How do we create a digital century and a digital future that can fulfil the aspirations of democratic people? Only in the past few years have we come to appreciate that the digital century is moving on a very different trajectory from the one that we had anticipated or that we would choose. This is the time. It is not too late, and not too early, for us to engage in this challenge and to create the needed legal frameworks, regulatory paradigms, new institutional forms and the new charters of rights that will assert democratic governance over the digital. This is the big work now. This big work is consonant with the challenges as developing individuals. The development of one cannot be alienated from the development of all.

Scholar, writer and activist Shoshana Zuboff is the author of three major books, each of which signalled the start of a new epoch in technological society. Her recent work, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, has been hailed as the tech industry’s Silent Spring. Zuboff is the Charles Edward Wilson Professor Emerita at Harvard Business School.

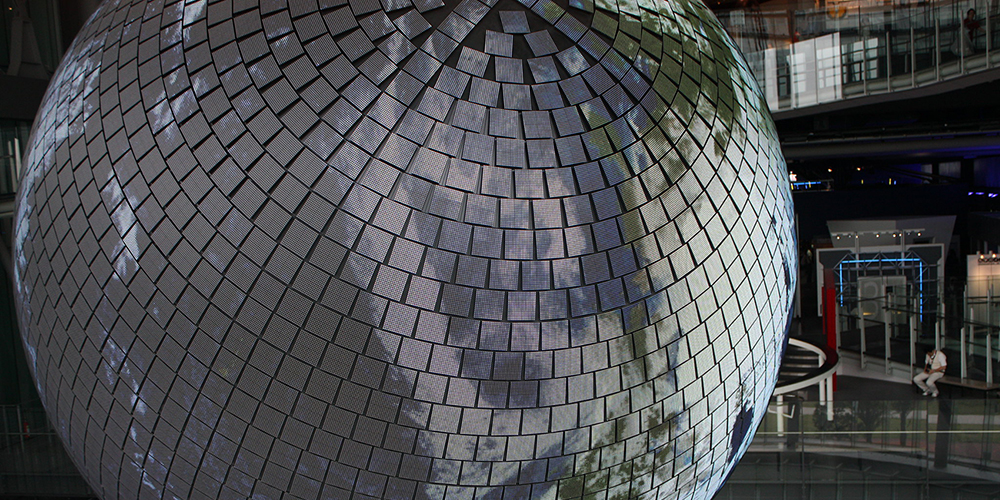

Cover image: by Baptiste Michaud via Flickr.