The changing nature of global warfare gives scientists a responsibility to ‘speak truth to power’ and uphold norms against the misuse of science, according to speakers at the World Social Science Forum’s final plenary session.

In 2018, 100 years since the Spanish flu pandemic, could an equally devastating global pandemic occur today? And is there a chance that such a pandemic could be human-made, whether released accidently during routine lab work, or deliberately started in order to create chaos? This was the question posed by Jo Husbands, Senior Project Director at the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, during the final morning plenary of the World Social Science Forum, on 28 September 2018. The session brought Husbands together with Andrew Feinstein, investigative journalist and head of Corruption Watch, for a discussion on new forms of conflict and the role of scientists. The moderator was Al Jazeera journalist Hoda Abdel-Hamid, and a video of the session is available.

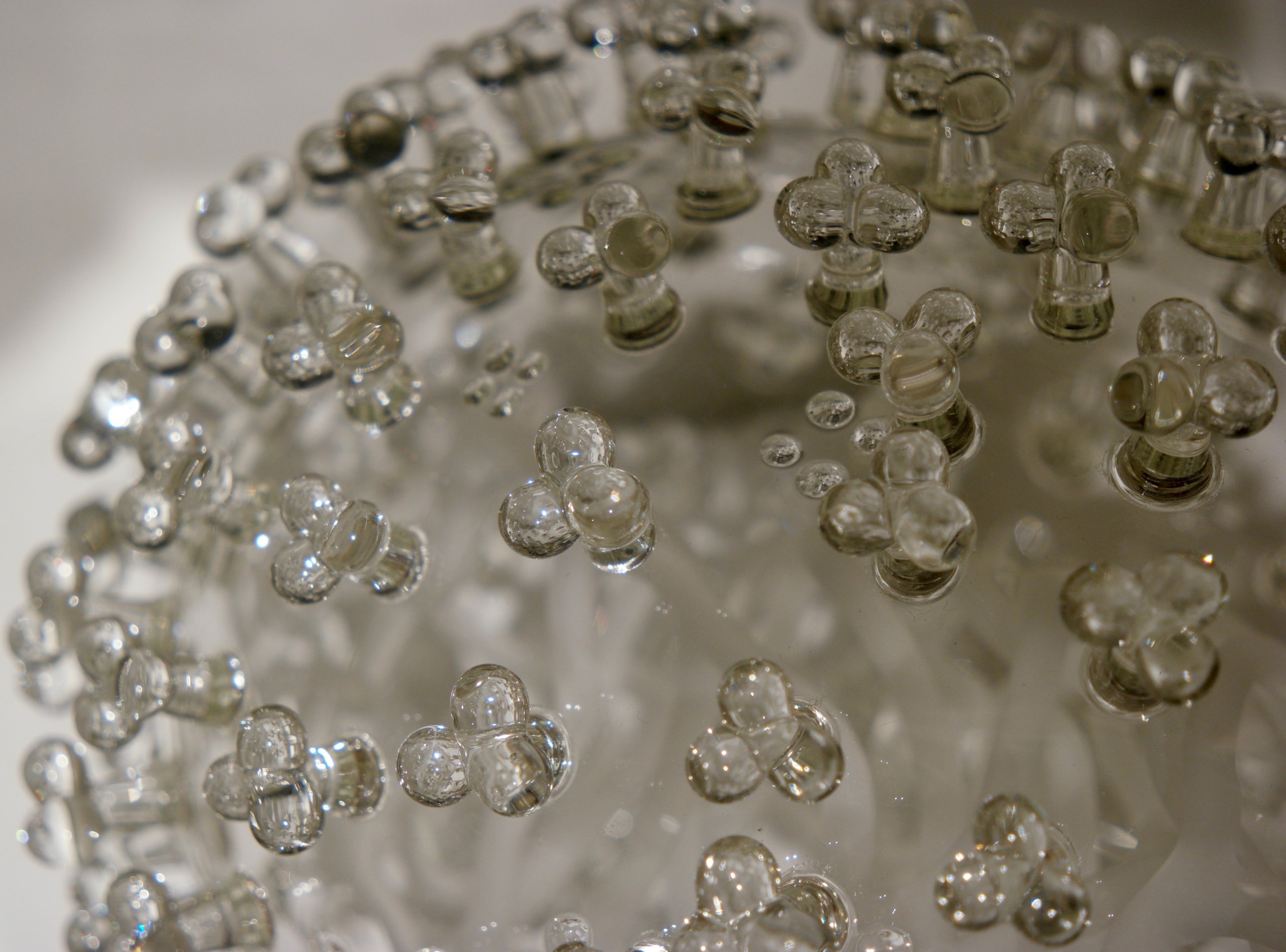

Scientific and technological advances – such as the development of autonomous weapons, or the use of synthetic genomics to engineer viruses – pose critical questions for scientific practice and ethics, particularly around the use of so-called ‘dual-use’ technologies.

However, Feinstein pointed out that while the modalities of warfare and weaponry are changing rapidly, the politics and economics of war and the arms trade have not changed. Corruption and bribery in arms deals is rife, and rarely investigated. Moreover, many arms deals operate in a ‘grey zone’ of legality and may be linked to organized crime networks, argued Feinstein. In light of this, there remains a risk that biological and chemical weapons, however difficult to create and store, could end up being sold to terrorist groups, he cautioned. In addition to the death and destruction wrought by the weapons themselves, the practices of the defense industry are undermining progress and democracy, leading Feinstein to conclude that the industry undermines rather than enhances security.

Technological progress and continued corruption make the role of scientists in the contemporary landscape of global conflict all the more important. Firstly, in providing knowledge and evidence about the implications of new technologies, and in ‘truth-telling’ about instances of corruption and bribery. There is a knowledge gap between policy makers and the engineers and scientists responsible for developing weapons and dual-use technologies, and a need for scientists to work with policy makers to help them understand the implications of scientific discovery.

“If I could voice one plea, it would be for scientists to focus on the accessibility of the work that they do, or to ensure […] that they work with people who can make that transition from an academic or scientific community to ordinary citizens”, said Feinstein.

The fuller integration of social and natural sciences, as promoted through the creation of the International Science Council, should facilitate these kinds of discussions, said Husbands. The social sciences have a particular role, through approaches to identifying and understanding risk (decision science), and advancing knowledge on culture – such as on how individuals behave in organizations or laboratories. In addition, the science of science communication has demonstrated that simply providing more information about a topic is not necessarily useful, and that there’s need to think about how issues are framed, such as whether new technologies are described as ‘autonomous weapons’ or ‘killer robots’.

Husbands called upon the scientific community to uphold norms against the misuse of science for malevolent aims, saying that international science organizations, networks and academies were powerful actors in helping to ensure that the norm of science for public good is not undermined. The question is not to seek a balance between science and security, said Husbands, nor to have one or the other; we can have both.

[related_items ids=”6798,3188″]