Picture a typical encounter at a government medical centre. At a public clinic in South Africa, a patient has been identified as high risk of diabetes. The attending doctor advises that they must manage their blood sugar through better nutrition and exercise. The doctor can then tick the box to say they have done their bit in advising the patient, and that the patient has heard and understood their advice.

In reality, both sides of this equation know that when the patient walks out of the clinic, living out the advice provided is nearly impossible. Once their feet hit the pavement, the patient is faced with significant environmental challenges that hinder their ability to do so: unwalkable cities, long commutes, limited food budgets, overcrowded living conditions, and so on.

Through this lens, it is clear that health is a social and economic concern, and a matter for urban planning and housing, as much as it must fall within the ambit of authorities like a health ministry. Given this, health itself is fundamentally transdisciplinary, and researchers are making the case for breaking down the siloes that encompass it, to work together with a broad range of authorities for better, healthier outcomes.

Dr Tolu Oni is one such researcher. A medical doctor by training, Oni segued into health research, attaining postgraduate degrees in public health and epidemiology. She is the principal investigator for a LIRA-funded project called “Integration of housing and health policies for inclusive, sustainable African cities” and is affiliated with the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences and Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge.

“The problem is most of the factors that influence health lie outside of the health sector, but only the health sector is held responsible for health,” Oni explains.

“Think about where most people in Africa live, in urban centres that are rapidly growing and not planned in the traditional way. Here, in this context, the way that the lived environment affects behaviour – in terms of how we live and what we eat – is a factor that must be considered within efforts to create health.”

“People make the most rational choices they can in terms of how to feed themselves and their households, based on what is accessible and what is feasible. Whether the access issue is one of geography or finances, many people spend most of their time traveling huge distances for work, and many of these cities are not conducive to being a pedestrian. So how do you make time for being physically active?” she asks. “We know that this puts a huge strain on public health provision, but conventionally no one is holding the planning authorities, for example, accountable for the fact that I’m unable to exercise which increases my risk of non-communicable diseases.”

This results in an ever-increasing demand for healthcare services, but a limited perspective of the interventions required. Oni’s team believe that there needs to be a ‘reinvention’ of human settlement development planning processes within African cities if these spaces are to meet Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11, which seeks to build resilient and sustainable cities, as well as Goal 3, which aims to improve health and well-being.

Their research focuses on Cape Town, South Africa, and Douala, Cameroon, as case studies. In the case of the former, Oni had on-the-ground knowledge of the conditions, and an established network of researchers and stakeholders to tap into. “There is demonstrable spatial and health inequality [at play here], which is an important thing to factor in when examining health at the population level,” she explains. For the latter, the researchers wanted a city to compare and contrast their Cape Town studies, and reached out via their networks for a partner in Cameroon. Here, Blaise Nguendo-Yongsi from the Faculty Institute for Population Studies at the University of Yaoundé II joined the team as Co-Principal Investigator (Cameroon). Other contributing parties include UCT’s School of Public Health and Family Medicine.

“I set up a research group at the University of Cape Town on urban health that aimed to take a different approach to thinking about creating health, beyond thinking of health as just disease management, and realizing we had to involve people outside of the traditional health sector.”

“I ran workshops with different policymakers from different sectors that have an influence on health, just to hear from them in terms of what their priorities were, and to look for opportunities to partner for health,” she explains. “The human settlement sector (specifically the Western Cape Department of Human Settlements (WCDoHS) expressed the most interest. They recognized that they did have an influence on health, particularly in the context of health in South Africa, but, with their core deliverables against which their performance was assessed, had little scope to focus resources on the health implications of their work.”

Next, the researchers cast a wider net, working with the Western Cape Department of Health (DoH) and WCDoHS to identify relevant people beyond the initial group, and with an eye to understanding the social determinants of health and what opportunities existed for different sectors to play a role. They also looked at what kind of barriers to this approach existed – those reported as experienced, and those perceived to be the case.

Phase one of the project mapped the landscape of relevant policies and existing government structures in both Cape Town and Douala, hoping to find “synergies and collaboration opportunities between the housing and health government sectors”. This was achieved through a combination of desktop research and interviews.

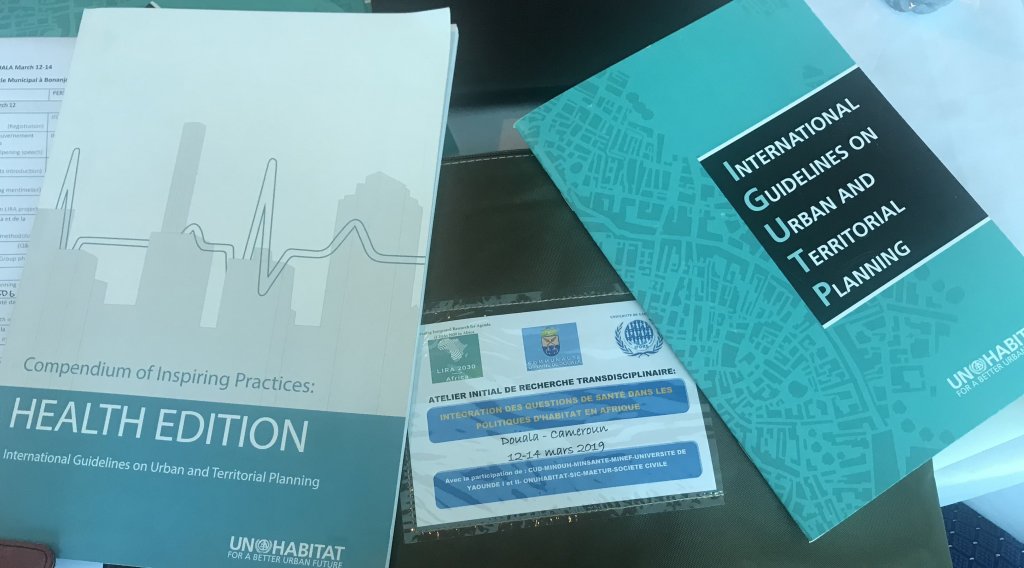

Phase two (ongoing) involves comparing and integrating quantitative data across government sectors, including from DoH and WCDoHS, with the aim of using these data to inform assessment of the health impact of things like housing interventions in poor areas of the cities. An important part of this work has the team focused on building up trust with stakeholders to enable buy-in for co-creation of the research agenda to co-implementation, necessitating data sharing. Vital to this process has been taking the time to understand the contexts within which stakeholders work and their achievements and prioirities, and then exploring together potential areas of collaboration with mutual benefit for their existing priorities. In Cameroon, the researchers have kicked off the policy-maker engagement dialogues with an intersectoral workshop that explored understanding of the role of health in urban planning, common environmental challenges that contribute to population health challenges, and brainstormed strategy to address these. This workshop was followed up by key informant interviews to further explore these intersectoral collaboration enablers, barriers and opportunities.

Having the buy-in from key partners in Cape Town (including the WCDoHS and DoH) meant that they could identify and isolate specific areas of intervention, such as a planned project upgrading an informal area.

An upcoming workshop in December 2019 will bring together partners from Douala and Cape Town as well as other urban actors from key cities in Africa to facilitate shared learning, build new partnerships, and identify and co-create new transdisciplinary research, co-developing and evaluating the impact of interventions in the urban built environment on population health equity.

“We are essentially aiming to integrate the housing and health data of a space, before the intervention, so that we stand a chance of being able to understand what the health impact of that was afterwards.”

“I hope to contribute to a rethinking of the governance and accountability for health,” says Oni. She knows that the evidence from this project is just one “cog in the machine” for rejigging public health, but believes that it goes some way to demonstrate what is possible if we take an inter-sectoral perspective for health and wellbeing policies. It also unpacks the matter of governmental performance indicators that can be realigned to reflect a more holistic view of health and the related value system. And that’s why she argues that “improving population health – equitably – has to be a brave and ambitious endeavour.”

If you are interested to learn more about Tolu Oni’s work resulted from the LIRA project, please see below:

This project is being supported by the LIRA 2030 Africa programme.