How do we begin to upgrade Africa’s informal settlements in achievable but meaningful ways? These spaces are an almost ubiquitous feature of African cities. With a history of patchy development, and in the face of the global trend towards urbanisation, African people have made inroads into urban centres by establishing informal settlements.

Informal settlements offer cheap and basic homes in close proximity to jobs and opportunities – but often their informal nature introduces challenges. These include overcrowding, lack of sanitation and sewage infrastructure, limited service provision, and sometimes significant safety and security risks. An additional challenge is that many of the civil servants who are tasked with upgrading these areas no longer reside in them (and possibly never did) or engage with the settlement residents – creating a top-down policymaking process that often disregards the real needs of the very people and areas they seek to service.

It is within this context that Dr Madelein Stoffberg is working to flip the story, collecting data and feeding it upwards – from communities to the public sector. She is the principal investigator of a LIRA-funded research initiative called “Community led upgrading of informal settlements in cities in Namibia and Zambia”, focusing on the cities of Windhoek and Gobabis (Namibia), Lusaka (Zambia) – and in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.

As a lecturer at the Namibia University of Science and Technology, Stoffberg saw first-hand the crisis of housing in Namibia where – according to the Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia – 995 000 people live in about 228 000 shacks across 308 informal settlements in urban areas, out of a population estimate of 2,5 million.

Her team brings together Namibian and Zambian academics (from various fields, including architecture and spatial production, housing, town planning, and urban development), non-governmental organisation (NGO) workers – Namibia Housing Action Group and People’s Processes for Poverty and Housing (Zambia) – and community members. Together they are mapping stakeholders and existing upgrade programmes, and creating a platform for people to tell their stories in the form of visual and spoken narratives.

“These settlements are growing, and there are many different possible ways to address this. Our idea was to look at it from a community perspective. Policy is important, but it doesn’t always take the people who actually live in these situations into consideration,” says Stoffberg.

In Windhoek, the team organized a learning lab called “Urban Dream”, which was organized in conjunction with the NGO partners and community leaders.

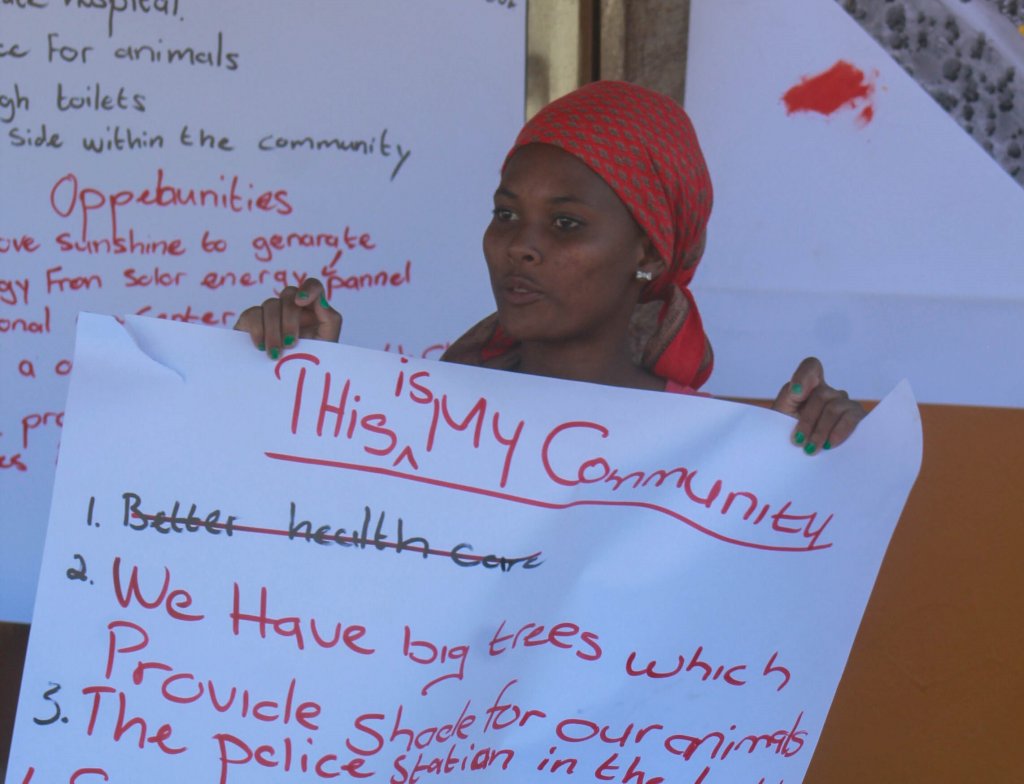

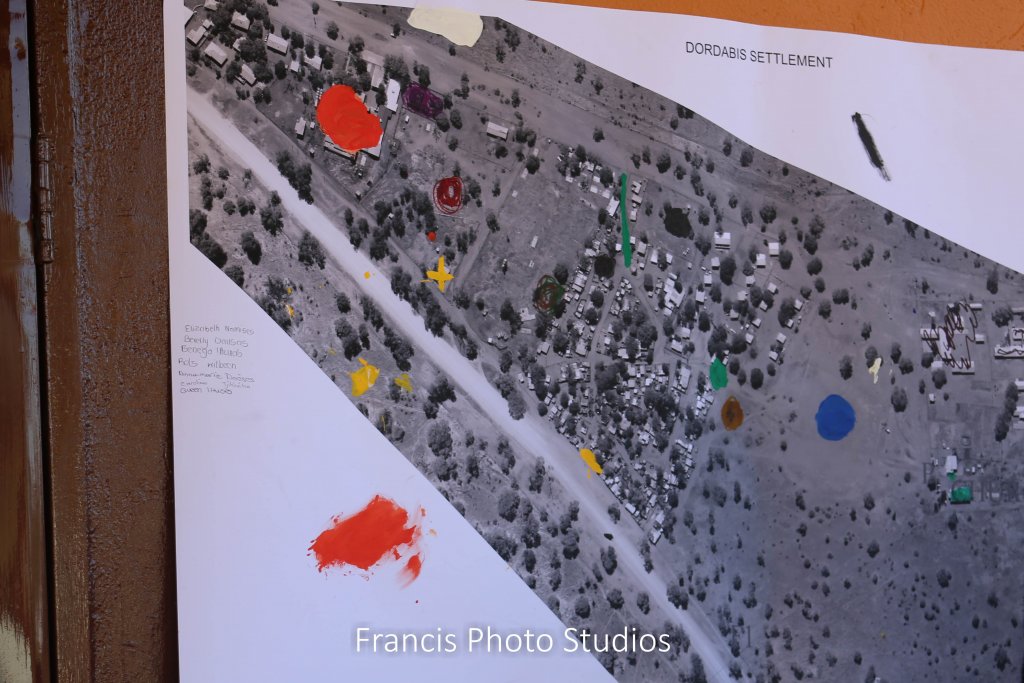

“We then formed six different groups that the community leaders led, each with the task of using a different medium to describe these communities’ urban dreams: where they are now, and where they would like to go in future,” explains Stoffberg.

The six mediums were:

“We received some incredible art depicting living conditions. The photography was also particularly interesting as the captured images didn’t only focus on negative aspects of informal settlements, but also examples where communities had already tried to improve their conditions by changing things like water drainage. It is clear the communities are trying to address their own concerns, and come up with innovative solutions.”

“The outputs,” says Stoffberg, “are definitely not traditional, but they are building towards a multifaceted collection of lived experience narratives. The next step is to translate these into solutions, and these would be cognizant of the restrictions and possibilities of municipal policy.”

The team is now, in 2019, undertaking the same narrative collection process in Lusaka. In Gobabis, the focus is on production of a case study, examining a community-led upgrade project that has already been implemented.

Government is another critically important stakeholder, but engaging them in the process hasn’t always been as straight forward as hoped. “We started the project with the intention of looking at how we can partner with government,” says Stoffberg.

“However, we encountered a hurdle in that the municipality has to answer to other leaders and constituencies, including national government, and that adds layers of complexity to the project.”

Representatives of Windhoek city government did participate in early workshops, first on data collection methods, and later on unpacking said data. That was then followed by a meeting with the management of the Windhoek municipality to understand the upgrade steps that they are following and their vision for these spaces. “Unfortunately at this point, it was clear that they were not keen on a direct relationship with us. So we changed back to primarily engaging with the community (as described above). With these narratives, we hope to describe the community’s concerns better, and use them to convince (and communicate with) the public sector stakeholders.”

Of course, informal settlements are not all the same, and this necessitates a tailored approach. “There are significant differences in both the municipalities and policies governing informal settlements in Windhoek and Lusaka, as well as in the structure of their informal settlements.”

“Any planned upgrade must start with understanding the problems in context, and then working from the broad to the specific,” she adds. “Often, the primary issue is no security of tenure for residents. Next, we need to understand the specific policies at play. After that, we could move on to proposing changes to things like layout and demarcation, and only then can one look at the housing itself and upgrading that.”

At every level, we know that we need to incorporate the community voice. Currently, they are not heard. It might be easier to work purely from a policy perspective, but then we wouldn’t be addressing the problem properly.