Negotiations at COP28 have crystallized on the “phase down” versus “phase out” fossil fuels debate – with no clear consensus. But the science is clear, and to quote UN Secretary General Guterres: “The 1.5C limit is only possible if we ultimately stop burning all fossil fuels. Not reduce, not abate. Phase out, with a clear timeframe.”

Now is the time to break through the political impasse and drive science-based, sustainable policy solutions to face the existential climate threat. Could the insights from social sciences hold the key to shift all interests towards urgent and meaningful action in addressing the fossil fuel issue?

“Thinking about how our modes of governance, our economies and financial systems are functioning is absolutely vital at this stage of the game,” explains Cameron Hepburn, Oxford Director of the Economics of Sustainability Programme, Professor of Environmental Economics and panellist in the recent ISC/Royal Society COP28 panel discussion.

A fossil fuel-free future is viable, and the economic case for accelerating the shift to renewables is strong and improving constantly, he argues. “The scientists and engineers have done the job,” Hepburn says. “So what’s holding us back? That is the question – and the answers are within the socio-political realm.”

“We’re at a point now where telling people in ever-greater detail that we’re doomed doesn’t move the needle at all, on public attitudes or on policy,” Hepburn notes.

The way through the political deadlock, the economist argues, will rely on science-based policies that make a fossil fuel-free future a financial inevitability.

“I’m not saying there’s a kind of Pollyanna approach, a really quick and easy set of small things that will get us sorted. This is a massive challenge, and meeting it is going to require the end of fossil fuels, effectively, and that is going to be resisted very powerfully,” Hepburn says. “The way to get there, I think, is to ensure that the clean competition is just more attractive, so that in fact you’re not fighting a political battle – fossil fuels have lost an economic battle.”

Those competing cleaner technologies are getting exponentially cheaper and better, he notes. For scientists, the key now is to find the policy ideas and social innovations that will encourage that process to move faster.

“Even more important now is to fuse that physical and social science to provide actionable policy advice,” Hepburn argues. “What works to bring down the cost? What works to get people to deploy these cleaner technologies?”

In the UK, he points out, investment in renewable energy is growing, but because of backlogs at the national energy regulator, many new projects won’t be connected to the grid for as many as 15 years – a problem that could be alleviated by adequately funding the regulatory process, Hepburn argues.

Another challenge: opposition to wind turbines, which some jurisdictions have approached by paying residents or cutting their power bills, or investing in community projects. Other challenges like improving energy use in new homes or limiting the environmental impact of plastics also require technical, policy and economic solutions.

Some of Hepburn’s recent research looks at the idea of “sensitive intervention points” – moments or innovations that unlock progress. Sometimes, those points are technological and economic – renewable energy becoming cheaper than burning oil, for example – while others come at a unique moment, like the COVID-19 pandemic or the current energy crisis, when social and political events create a window of opportunity for big changes.

Often, a concept is just as – or more – impactful than any single piece of technology, he notes: “If you think about the key innovation of the last 600 years, maybe it was the steam engine, maybe it was the coal-fired power plant – or maybe it was the concept of the limited liability corporation, which is a social-scientific concept that then effectively enabled those other concepts from the physical sciences to be exploited by human systems.”

Using the sensitive intervention points framework, Hepburn and his colleagues evaluated possible climate interventions and ranked them according to criteria including potential impact, risk and difficulty – an example of a framework policy-makers could use to choose the best, fastest ways to make changes.

Technological progress can take us only so far – it effectively needs economists and other social scientists to suggest policies that make it practical and possible to implement. “We’re effectively reimagining the world economy, and we’re going to need a lot of science to do that properly,” Hepburn says.

According to a recent report by the Royal Society, enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration among physical scientists, economists, and other social scientists can bridge the long-standing disconnect between these disciplines in the context of climate change. This collaboration is crucial for gaining a better understanding of the economic and social implications of extreme events and climate-induced hazards and providing urgently needed insights to reach political consensus.

Social science will also be key to answering new questions raised by the green transition, notes Maria Ivanova, Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University.

“It is not sufficient just to know what the problems are. We have to think and we have to propose what needs to be done,” says Ivanova. “That’s where social science comes in. We know what the problem is. So what ought to be done?” adds Ivanova, who is also an inaugural Fellow of the ISC and part of the Technical Advisory Group to the ISC’s Global Commission on Science Missions for Sustainability.

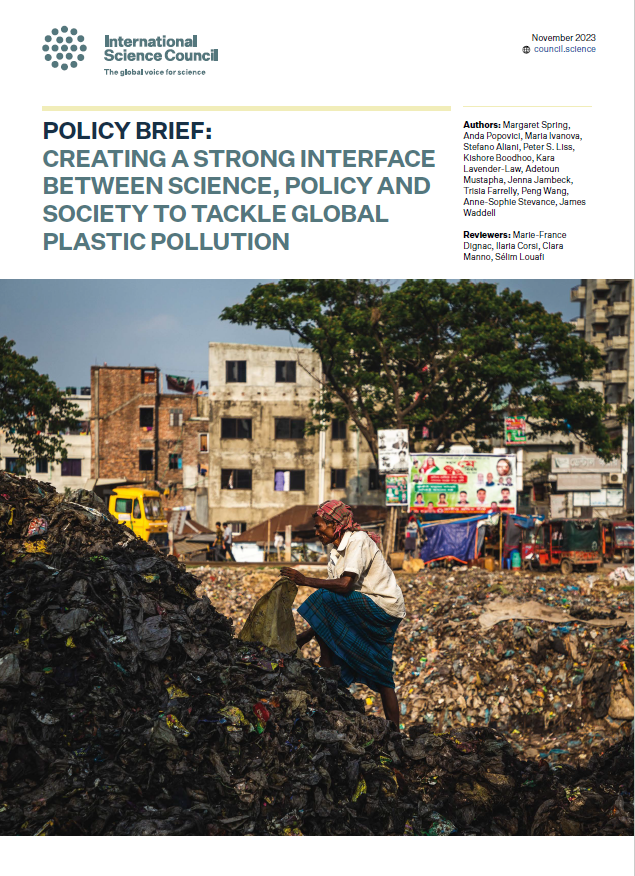

Ivanova just returned from the third round of negotiations in Nairobi on a new global treaty to end plastic pollution – a process led by Rwanda and Peru, who have pressured the international community to develop a plan to address the 430 million tons of plastic produced every year.

Ivanova has worked with the Rwandan delegation since 2022. The negotiations have been challenging and are still focused on key details, including the scope of the treaty and a debate over setting binding targets versus letting countries choose how to cut.

Policy Brief: Creating a Strong Interface between Science, Policy and Society to Tackle Global Plastic Pollution

In the midst of an escalating global crisis, the International Science Council (ISC) has released a Policy Brief calling for the urgent establishment of a robust science-policy-society interface to tackle the persistent and long-term issue of global plastic pollution.

Because plastics are so ubiquitous, dramatically cutting their use means addressing a variety of issues and creates new challenges to solve, Ivanova notes – like understanding how changing packaging could affect food deserts, or finding a way to support waste pickers whose livelihoods depend on discarded plastic. And there’s another unsettling possibility, rooted in economics: in a future where fossil fuel companies have to reduce emissions or stop producing fuel oil because of declining demand, will they just pivot to plastics?

These issues of environmental justice and economics all need a social science lens to understand and address, Ivanova explains. And with strong scientific evidence driving ever-greater public awareness and demands for change, those same lenses will be crucial to thinking about how to implement solutions.

“In confronting climate change and plastic pollution, we are dealing with crises that are not static and do not have one-time fixes,” Ivanova says. “Our responses must be dynamic, evolving with the challenges. It is not merely about adjusting certain metrics – it is about understanding the deeper complexities of human behavior and collective action through social science. And critically, interdisciplinary, experiential education is fundamental to enable the human connection to mind and heart that would lead to responses that are both just and effective.”

From the climate emergency and global health to the energy transition and water security, the ISC and its high-level Global Commission on Science Missions for Sustainability argue that global science and science funding efforts must be fundamentally redesigned and scaled up to meet the complex needs of humanity and the planet.

As described in the report Flipping the Science Model: A Roadmap to Science Missions for Sustainability, the Commission calls for a ‘mission science’ approach, meant to overcome the fragmented, compartmentalized scientific knowledge that often fails to connect with and to address society’s most immediate needs. It seeks to work in a transdisciplinary, collaborative way that is demand-driven and outcome-oriented.

The science is clear, it has been for decades: our planet’s climate is warming, and human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels, are the primary drivers of this change. Following recent developments at COP28, Future Earth and the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), two Affiliated Bodies of the ISC, have convened a statement from scientists around the world in response to comments regarding fossil fuel phaseout pathways. If you are a scientist, you can support the statement with your signature.

Photo by Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash.

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in our guest blogs are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council