This comprehensive paper by the Centre for Science Futures, the ISC’s think tank, addresses the urgent need for a new and proactive approach to safeguard science and its practitioners during global crises. With many conflicts spread over vast geographical zones; increasing extreme weather events due to climate change; and natural hazards such as earthquakes in unprepared regions, this new report takes stock of what we have learned in recent years from our collective efforts to protect scientists and scientific institutions during times of crisis.

“Critically, the report comes at a time when schools, universities, research centres and hospitals, all places which promote the advancement of education and scientific research, have been places of conflict, and destroyed or damaged during the Ukraine, Sudan, Gaza and other crises. We in the scientific community must reflect on the creating the enabling conditions for science to survive and thrive.”

Peter Gluckman, President of the International Science Council

Protecting Science in Times of Crisis

International Science Council. (February 2024). Protecting Science in Times of Crisis. https://council.science/publications/protecting-science-in-times-of-crisis DOI: 10.24948/2024.01

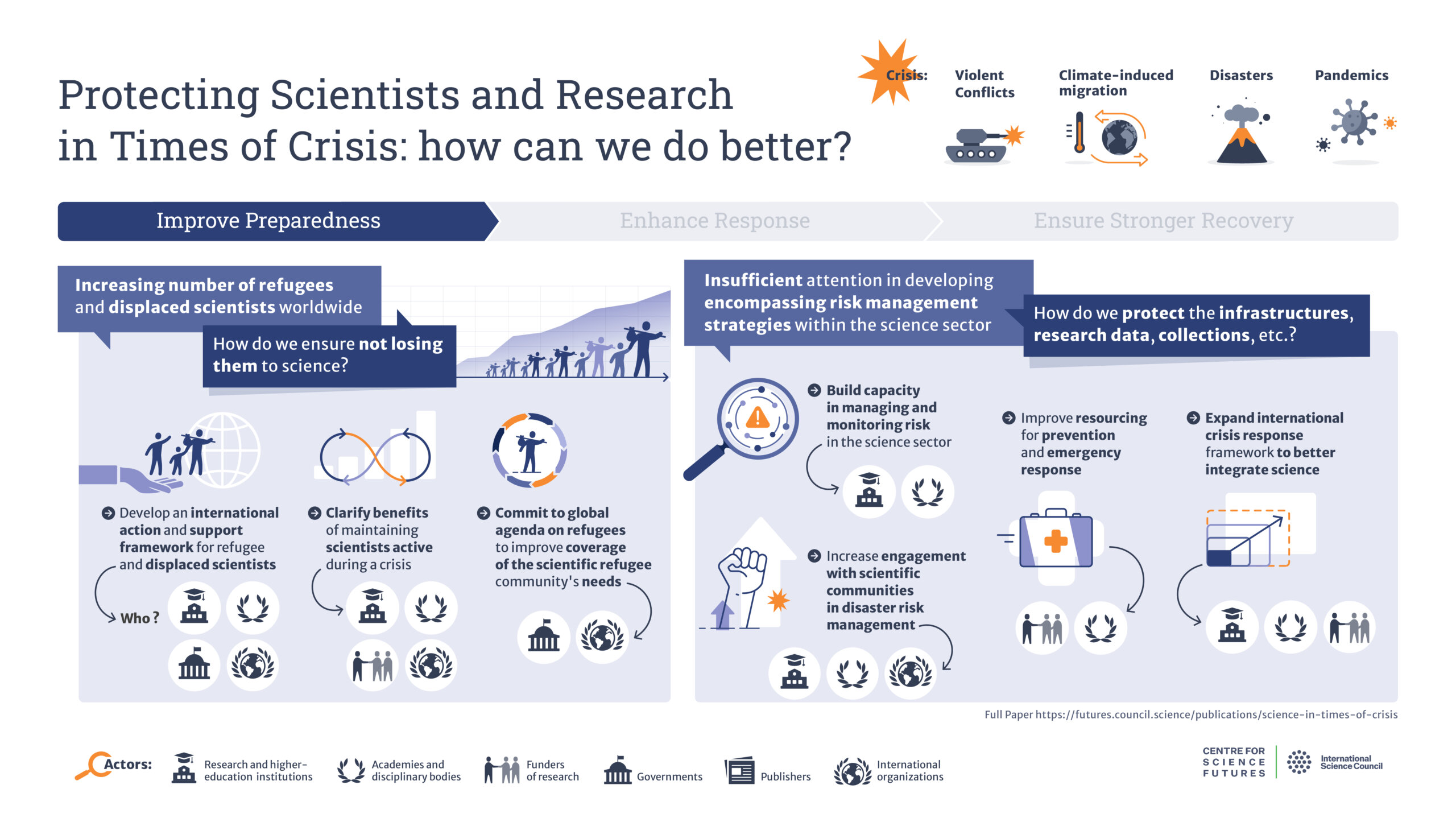

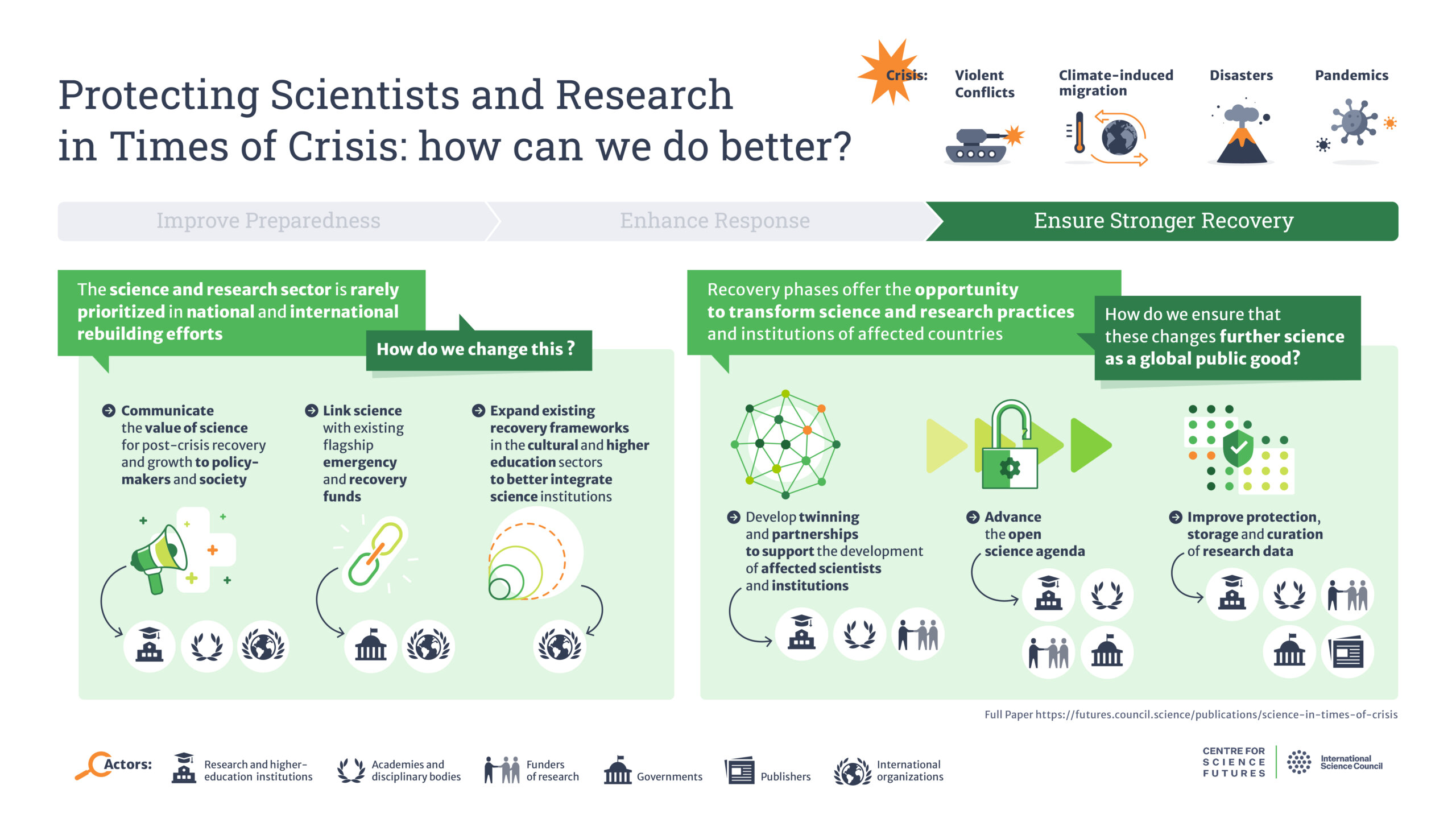

Full paper Executive SummaryIt proposes a practical set of concrete measures, following the stages of humanitarian response, that are meant to be jointly implemented by the best-placed public and private actors in the international science ecosystems. It also identifies how existing policy frameworks can be enhanced, including specific amendments to current international treaty and regulations.

The current number of refugee and displaced scientists can be estimated at 100,000 worldwide. Yet, our response mechanisms merely mean a temporary solution for a fraction of that number. At a time when the world urgently needs knowledge from all parts of the world to address global challenges, we cannot collectively lose all that science and global investment in research.

“With this new publication, the Centre for Science Futures ambitions to fill an important gap in the discussions on the protection of scientists and science during crises. The study details options for more effective multilateral policy agenda, as well as action frameworks that science institutions can start collaborating on immediately”

Mathieu Denis, head of the Centre for Science Futures of the International Science Council

Echoing UNESCO’s 2017 Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers, the paper provides insights which can help shape future consultations within global and national science systems on how to act on the UNESCO 2017 recommendation.

Accompanying the paper is a set of infographics and an animated video to illustrate the actions that can be taken by the science community and relevant stakeholders during each of the three phases of the humanitarian response. These materials are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. You are free to share, adapt and use these resources for non-commercial purposes.

The ISC is urging international scientific institutions, governments, academies, foundations, and the broader scientific community to embrace the recommendations outlined in “Protecting Science in Times of Crisis”. By doing so, we can contribute to a more resilient, responsive, and prepared scientific ecosystem capable of withstanding the challenges of the 21st century.

📣 Share the word and join us in our efforts to build a more resilient science sector. Download our media and allies amplification kit and see how you can help.

The key findings of this paper are organized in alignment with the phases of humanitarian response: prevent and prepare (the pre-crisis phase), protect (the crisis response phase), and rebuild (post-crisis phase). A summary of the main findings is given below:

Prevention and preparedness (pre-crisis phase)

Protect (crisis-response phase)

Rebuild (post-crisis phase)

The findings from our work to date suggest that too often, the scientific community’s response to crisis remains uncoordinated, ad hoc, reactive and incomplete. By taking a more proactive, global and sector-wide approach to building the resilience of the science sector, for example through a new policy framework, we can realize both monetary and social value for science and wider society.

Image of the National Museum of Brazil by AllisonGinadaio on Unsplash.