Originally published by the Global Research Programme on Inequality (GRIP)

“We fear that 2020 will be a lost year in global development”, says Paul Richard Fife, Director of the Department for Education and Global Health at Norad, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. Norad is first up in the Global Research Programme on Inequality’s (GRIP) miniseries of interviews on the current COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on the multiple dimensions of inequality.

We are already seeing how the impacts of the COVID-19 are unevenly distributed depending on where you live, your job situation, age, class position, gender, ethnicity, the availability of health services, and a range of other factors. In this series we provide short interviews with scholars and relevant organisations that share their insights and views on how the pandemic might exacerbate or alter existing inequalities across six key dimensions: social, economic, cultural, knowledge, environmental and political inequalities.

First up in our series is an interview with Paul Richard Fife, who is the director of the Department for Education and Global Health at the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

How does the COVID-19 epidemic influence development interventions in the global South?

These are still early days and we will know much more about the impact of COVID-19 in low-income and fragile settings over the next few months. We fear that 2020 will be a lost year in global development. We are already now getting reports that COVID-19 is disrupting or delaying programs in countries hit by the virus. Restrictions on movement have been imposed in many countries and this impacts directly on staff movement and implementation of programs.

The situation in-country is compounded by international bottlenecks such as travel restrictions and supply chain difficulties, including medicines and personal protective equipment for health staff. Food prices are more likely to increase due to the pandemic. While not only due to COVID-19, the global economic downturn and fluctuating currency exchange rates may also impact on the level of external aid flows to developing countries.

How will a potential delay in these projects affect the target groups? Which interventions are most at risk of adverse negative effects of such delays?

As countries now attempt to contain COVID-19, an immediate consequence is the soaring number of children and youth not attending schools or universities. Hundreds of millions of students all over the world are losing out on education opportunities. As the virus starts to circulate in communities, health services will rapidly get overwhelmed. This will impact not only on countries’ ability to care for COVID-19 patients, but for all other health services. If larger portions of the population get sick or need to care for their relatives, productivity will decrease with wide-ranging consequences for families, businesses and the national economy.

It is important to underscore that COVID-19 is not only a global health and humanitarian crisis, but also a broader social, economic and political crisis. We can expect serious disruptions and delays in all sectors and programs until the pandemic burns out or an effective vaccine or treatment against COVID-19 is universally available. To complement the emergency health and humanitarian response, it is important from the start to prepare for mitigation and recovery. COVID-19 is a reminder that building resilience to crisis and shocks is an integral part of our collective efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and leaving no one behind.

What are your immediate thoughts on the long-term and medium-term impact of this epidemic on development policy and with regard to inequality?

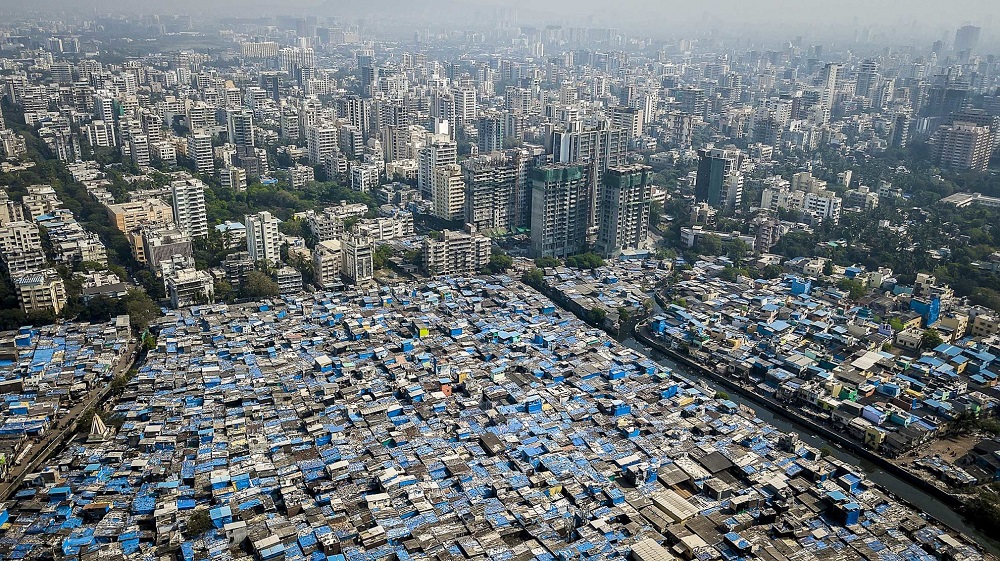

As with other crises, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates underlying vulnerabilities and inequalities across and within countries, including income and gender inequality. From earlier epidemics, we know that the poorest and most vulnerable groups, such as refugees and people living in cramped conditions with poor hygiene and clean water supply, are at the highest risk of catching the disease and have limited access to healthcare. For many, social distancing and home quarantine will in practice be impossible. The majority of workers in developing countries are employed informally and have limited savings. Without social safety nets, it is difficult for them to be out of work and they will be more vulnerable to catching the virus themselves. The World Bank estimates that 100 million people fall back into extreme poverty each year due to unexpected catastrophic health expenditures. This number is likely to increase due to COVID-19.

We see that some countries in the global South are handling the COVID-19 crisis better than countries in the North, mostly due to their experience in handling previous epidemics. What can be done to enhance more communication and knowledge-sharing between the North and the South (particularly from South to North) in this regard?

It is right that developing countries with recent experience in fighting epidemics such as Ebola, are to some extent better prepared for COVID-19. Existing Ebola screening systems have rapidly allowed to screen for coronavirus disease at airports and border crossings. More than 20 countries in Africa can now test for COVID-19. It is also helpful that infrastructure needed to isolate and treat severe cases is already in place in some countries.

Experiences with Ebola and other epidemics have also highlighted the need for public health communication through trusted channels to help reduce misinformation, prevent stigma and discrimination and keep public trust in national and local authorities.

Joint learning and knowledge exchange across countries is key for an effective response. Multilateral expert organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) play a key role in advising national authorities. Researchers, practitioners and media can also contribute with insights and information-sharing. However, country contexts differ and epidemics management often has a strong domestic focus, in part driven by public opinion. Contributions need to be relevant, timely and evidence-informed.

The next interview in this series will be published the coming week.

Photo: Johnny Miller / Unequal Scenes