The International Science Council and its members have long been proud champions and practitioners of evidence-informed policymaking. Advising decision-makers at national, regional and global levels on wide-ranging policies, international science NGOs like the ISC have produced hundreds of statements, declarations and reports, supported by thousands of peer-reviewed papers, as well as hosting countless events and workshops. These multiple outputs continue to draw on a wealth of existing knowledge and technologies that are ready to be applied for environmental and societal benefit, if the political will is there.

But it is increasingly evident that the political will is not there; that the current trajectory of national and multilateral policymaking is either too slow or heading in the wrong direction entirely, with politics appearing to disengage from environmental crises in many countries e.g. Spiers, 2024. Meanwhile, the world is getting hotter, greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, extreme weather events are more frequent, the disparity between the rich and poor more acute, and our world is in the middle of a sixth mass extinction. Decades of evidence and advice are not being listened to and acted upon, nor with the scale and speed that is required to mend our broken planet. The world risks missing “a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future” (IPCC, 2022).

The starkest example of political failure is the policy response to climate change. The scientific consensus that humans are altering the climate is overwhelming (The Guardian, 2021; The Conversation, 2021) but traditional scientific interventions (government scientific advisors, advisory bodies, statements, reports, workshops etc) are not getting sufficient policy traction. Yet still the science community continues to mass-produce well-intentioned outputs regardless, often without critical evaluation; similarly, established international science fora produce “declarations” that are posted to their respective websites in perpetuity but essentially ignored in practice. A more critical commentator could argue that these well-worn, conventional methods are largely recreational, and parallel the science community’s obsession with written output and bibliometrics over genuine societal engagement and policy impact. At least one commentator has even accused scientists of being complicit in climate denialism by not calling out “incontrovertible truths” (Porrit, 2024). So, what more can scientists do?

Exasperated with the lack of political progress, and on the principle that scientists have an obligation not just to describe and understand the natural world but also to play an active part in helping to protect it, some scientists have turned to more activist approaches to convey their messages and draw attention to the climate and ecological crises (Nature, 2024). Continued government inaction, they believe, now justifies direct action, peaceful non-violent protest, and civil disobedience to expose the reality and severity of the climate and ecological emergency; in some but not all cases beyond the bounds of current laws as a last resort in this existential crisis. Scientists, they argue, have a moral imperative: with knowledge, comes great responsibility. Further, scientists are largely a trusted and privileged community that can bring legitimacy and credibility to social activist movements.

A growing number of scientists are getting involved in science activism all over the world (The Conversation, 2023), including supporting NGOs and professional lobby groups – like Greenpeace, World Wildlife Fund and Friends of the Earth – and more disruptive, bottom-up social movements. The global movement XR (Extinction Rebellion), for example, includes a growing scientific community – Scientific Rebellion – that provides a platform to inform, educate, share and rally support and is located in over 30 countries (you can read their declaration of support here). This community produces newsletters, run talks, events, campaigns and demonstrations to help scientists transition to more active roles. Any scientist in any discipline, anywhere in the world, can get involved.

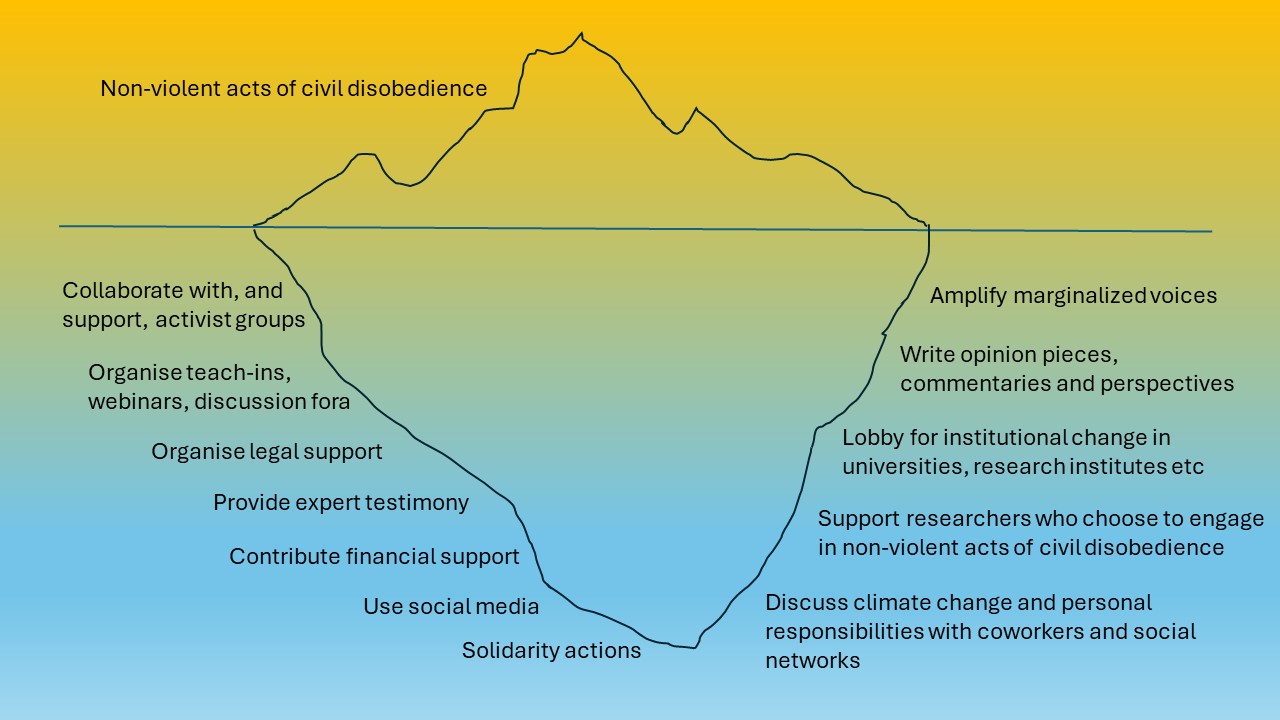

Science activism can take many forms and can best be illustrated as an iceberg of actions (Figure 1). Those operating in the orange area – demonstrating publicly and practicing civil disobedience – are supported by many others working behind the scenes in the blue area. Scientists do not have to be arrested to be more activist, but history tells us it is a necessary part of any impactful social movement.

Informed by the climate justice, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements, a new generation of science activists are beginning to shift the cultural norms of science, including institutional acceptance and engagement, and perhaps even research evaluation in time. Indeed, there are early indications that science activism may be gaining legitimacy within the scientific community, fuelled by social media (Tormos-Aponte et al, 2023). But science activism should supplement not replace the more traditional efforts of international non-government science organizations.

Science activism is a trade-off of rewards and risks. It can add societal purpose to research, connect scientists to society (and to each other), and help political decisions be addressed in meaningful and rigorous ways. Activism is a way to protest against glaring injustices perpetuated by laws, policies and economies fuelling climate and ecological crises. Just look at the recent landmark ruling by the European Court of Human Rights in April 2024 that political inaction on climate does violate human rights. But activism can also entail some level of personal, institutional and/or professional risk, and these risks can depend on geography, ethnicity and local research culture e.g. those living under less tolerant regimes (Tormos-Aponte et al, 2023). Some research institutions, representative bodies and individual scientists may find these risks too high and be reluctant to get involved, whether through the perceived politicization of science or compromising relations with vital stakeholders and funders. But the global stakes of not getting more involved are even higher.

The presently small community of activist scientists can have more impact if it grows rapidly in numbers and creates a critical mass of scientists all over the world. The global science community is naturally collaborative and interconnected, and can be a powerful conduit for raising the profile of this growing activism through its professional networks.

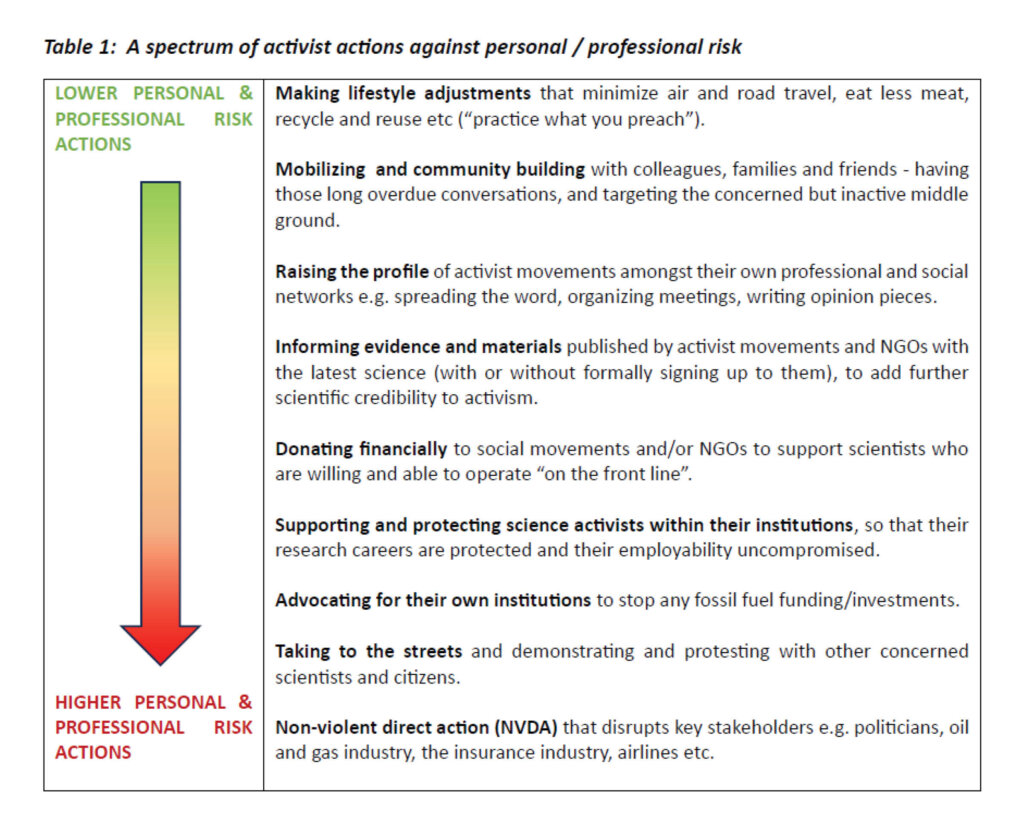

Involvement in science activism must be an individual decision, based on practical, ethical and moral considerations. Scientists can be more activist in multiple ways, where their positions, skills, expertise and networks can be invaluable (see Table 1, a spectrum of activist actions).

In conclusion, if scientists – whatever their discipline, country or career stage – feel compelled to do more and get involved in science activism, then investigating activist groups such as Scientists for Extinction Rebellion could be an interesting place to start.

Please share this blog too! After all, “Now is the time to mobilize, now is the time to act, now is the time to deliver” (UN Secretary-General, 2024).

Dr Tracey Elliott is a former consultant and project manager to both the ISC and InterAcademy Partnership.

Image by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in our guest blogs are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council