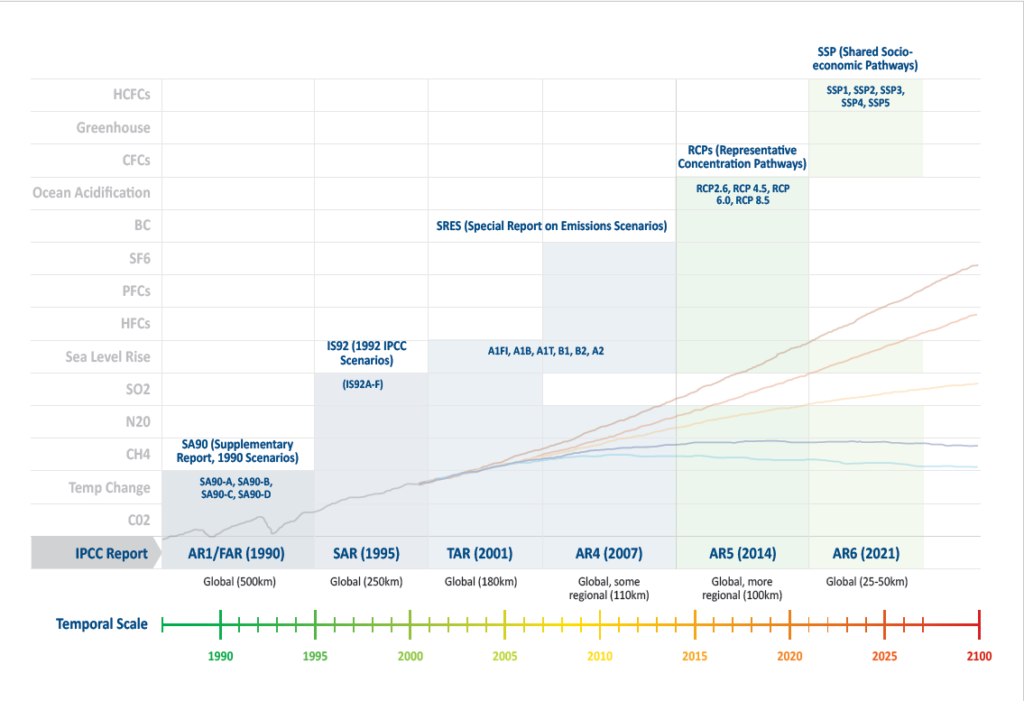

The scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports are critical instruments in our understanding and response to climate change and serve as a scientific foundation for global climate action. They provide scientifically rigorous, peer-reviewed projections of future climate conditions under different greenhouse gas emission pathways. From the “SA90” (Scenario A from 1990) in the First Assessment Report (AR1) to the Shared Socio-economic Pathway (SSPs) in the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), these scenarios have evolved in complexity and precision, reflecting our growing understanding of the climate system and the increasing sophistication of modeling techniques to assist public and private sectors on strategic decision, climate change risk assessment and adaptation planning. These scenarios are essential for informing policy because they provide a range of possible futures, each corresponding to specific assumptions about socio-economic development, technological progress, and mitigation efforts. By outlining the potential consequences of different emission trajectories, they enable policymakers to assess the risks and trade-offs associated with their decisions.

Moreover, scenarios help to quantify the impacts of climate change at global, regional, and local levels. They provide crucial data for climate impact assessments, informing strategies for adaptation and resilience building. These scenarios also play a pivotal role in economic analyses of climate change, helping to identify cost-effective mitigation strategies and guiding investments towards low-carbon development and climate change adaptation measures.

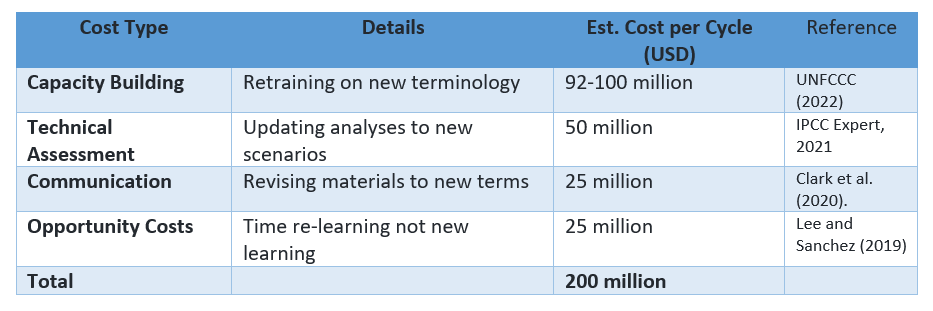

Over the course of the past six IPCC assessment cycles, the naming conventions and frameworks for socioeconomic and emissions scenarios have changed. While intended to utilize updated scientific information, this shifting terminology creates significant confusion to national governments, and to sectors who need to incorporate scenarios in their planning and policy makers. Significant challenges are encountered due to lack of knowledge on understanding scenarios, interpretation and transition costs for climate risk assessment using new scenarios and capacity building of national and local stakeholders and legislative changes. Changes of vocabulary could create technical, social, financial, and capacity building challenges. Evidence from past assessments revealed that around USD 200 million was spent in transition costs across IPCC reports due to terminology shifts. This could amplify significantly for countries capacity building, risk assessment and changes in legislations and policies. IPCC should use nuanced scenario vocabulary after AR6 and utilize consistent terms through at least Seventh Assessment Report (AR7), and potentially following assessment cycles in the future.

The IPCC assesses scientific literature to provide policymakers with regular comprehensive updates on the state of climate change science. Key components of these assessment reports are the socioeconomic and emissions scenarios that feed into climate model projections. The scenario development process is led by independent modeling groups running complex climate and Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs). For the recent IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), the core scenario modeling group was Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP), part of the larger Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6). Now, climate modeling has moved into the next phase, CMIP7, which will generate new scenarios and projections to feed into the upcoming IPCC AR7.

Scenario analysis is a critical component of IPCC climate assessments and IPCC has evolved its scenario vocabulary over time to reflect advancements in scientific understanding and to provide more comprehensive assessments. However, the naming conventions and frameworks for these scenarios have changed with every assessment report (AR) cycle, alternating from SA90 to IS92, SRES, RCPs and now SSPs (IPCC, 2021). While this updating resembles the improvements in scenarios, the shifting vocabulary increases transition costs for climate assessment, policy changes and capacity building (Nakicenovic, 2000). Table 1 summarized the IPCC scenarios, model accuracy, limitations and benefits.

The new IPCC assessment cycle (AR7) is just starting, and proposals for new scenarios are being published, such as TEWA: “The Emission World Avoided”, NFA: “No Further Action”, DASMT: “Delayed climate Action and Stabilization pathway Missing Target”, DAPD: “Delayed Action Peak and Decline”, and IAPD: “Immediate Action Peak and Decline” (Meinshausen, 2023).

However, while these names might appear more intuitive, and serve the scientific demand for diverse scenarios (Meinshausen 2023), the continual shift in terminology and scenarios across IPCC assessment reports can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations among scenario users, such as the impact community, financial sector, and climate services. Additionally, it can present challenges in data compatibility and integration. In the shift towards digital twin technology, maintaining vocabulary consistency is also pivotal.

We outline here several challenges on IPCC scenario vocabulary:

Confusion and Misinterpretation: Changes in scenario vocabulary leads to confusion among policymakers, researchers, and the general public (Parson, 2007). Familiar terms and concepts may no longer align with the new vocabulary, resulting in misinterpretations of findings and hindering effective decision-making. The use of acronyms like SRES, RCPs, and SSPs can be confusing, especially for non-experts trying to interpret the reports. It takes time to learn what each one stands for. The IPCC’s scenario names could also be confusing because they are not always consistent with the way that people use language. For example, the IPCC’s A1B scenario is a scenario in which global greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase throughout the 21st century. However, the term “A1B” does not have a clear meaning outside of the climate science community. This could make it difficult for people who are not familiar with climate science to understand the A1B scenario.

Communication Challenges: Vocabulary plays a crucial role in communicating and facilitating a common understanding of complex concepts. If language and terms change, it can be challenging to communicate the scientific findings effectively to policymakers, stakeholders, and the public, hindering the development of informed policies and actions. Terms like “representative concentration pathways” or “shared socioeconomic pathways” are not intuitive or easily understood by non-experts. Simpler language would help increase clarity and understanding.

Transaction costs and capacity building: Transaction costs and capacity building needs: Alterations in scenario terminology not only lead to transaction costs but also demand substantial resources for capacity building among national governments and policymakers (Rozenberg, 2014). This encompasses the retraining of personnel, revising guidelines, and realigning policies with the updated vocabulary. Such expenses can be significant, detracting from other essential areas. For example, the transition from the UK Climate Projections 2009 report to UKCP18, which updated scenarios from SRES to RCPs, necessitated the retraining of civil servants, adjustments in planning processes, and communication of revised projections to stakeholders based on the altered scenarios. These transaction costs resulted in policy implementation delays. Additionally, introducing new scenarios requires effective communication strategies to ensure clarity for the media, the general public, and decision-makers acquainted with older scenarios, ensuring they grasp and adopt the changes seamlessly (Geden 2015).

Lack of consistency: The shift from SRES to RCPs between AR6 (2021) and AR5 (2013) and previous IPCC reports within certain years represents a completely different framework and assumptions. This makes direct comparisons across reports difficult. However, it also gives an opportunity in the research community to understand model limitations and improvements.

Scenario myriad: Within each report there are multiple different scenarios used (e.g. RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, RCP8.5). For users often the question arises which of those to use, which one is more likely, plausible or relevant (note, by definition, there is no probability assigned by the IPCC to any of the scenarios). Some of the scenarios (e.g., RCP8.5) have been claimed as unrealistically within even one assessment cycle. Moreover, framing emissions as the ‘business as usual’ narrative can be misleading g (Hausfather and Peters 2020,. Having projections from both global and regional climate models adds further complexity in terminology and interpretation (see e.g. Ranasinghe et al. 2021).

Data standard and inter-operability: Changes in scenario vocabulary leads to inconsistencies in the data used for machine learning or AI assessment. AI models often rely on historical data and projections based on specific scenarios. If the vocabulary changes, the data used for training and evaluation may no longer align with the new terminology, leading to inaccurate results and biased assessments. Changing from RCP to new SSP scenarios training data would not interoperate seamlessly and it requires preprocessing to transform the inputs/outputs to the expected SSP terminology (Eyring et al, 2016). This could introduce errors if not handled properly in adapting the AI systems.

Model adaptation: AI models are trained to recognize specific patterns and relationships within the data. Changes in scenario vocabulary require retraining or adapting these models to ensure they understand and interpret the new terminology correctly. This process can be time-consuming, resource-intensive, and may require substantial adjustments to the model architecture. For example, if we develop a simpler model (neural networks) to mimic complex ones, saving computing power. These simpler models are trained on specific scenarios (e.g. RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5). The training data’s input labels and corresponding output variables would need to be transformed to match the new SSP scenario vocabulary and updated model outputs. Retraining on new labeled data is often not enough, as the relationship patterns between inputs and outputs may have changed in the new scenario framework. This could necessitate altering the emulator neural network architecture itself – adjusting the number of layers, nodes, connections to enable learning the new associations.

Transfer learning: Machine learning models trained using existing scenario vocabulary might struggle to transfer their knowledge to a new vocabulary. This can limit their ability to provide accurate assessments or predictions under the new terminology, making it necessary to invest significant resources in retraining or building new models from scratch. The scale of the assessment has also changed over time. The early reports focused on global impacts. However, more recent reports have included regional and local impacts. This has allowed for a more detailed assessment of the potential impacts of climate change. However, it makes it difficult to compare the assessment of various versions of models.

Transition cost: The scenario vocabulary cost could be considered as transition costs and it could be looked at based on capacity building, technical assessment, data analysis, policy development, communications and opportunity cost only to relate with scenarios. The overall transition cost to new vocabulary is shown in Table 2.

This indicates strong evidence that shifting terminology, vocabulary incurs substantial technical, financial, and learning about scenario costs, while providing only marginal benefits over framework lock-in. If we consider the whole global community, the transition costs of applying vocabulary changes could be more than expected. Inclusion of climate science in policy can be done in a targeted manner, substantial capacity building is essential to produce the usable science needed for informed policy making over decades.

The costs of capacity building on climate science to countries and the costs of including climate science to policy are significant. However, these costs are necessary to address the challenges of climate change. The IPCC should maintain consistency in terminology across assessment cycles. This would reduce the transition costs associated with scenario vocabulary changes and would make it easier for policymakers and the public to understand the IPCC’s scenarios. Furthermore, consistent vocabulary is essential for machine learning and AI models to effectively process and interpret natural language (Miller, 2019). This consistency allows models to numerically represent words, grasp contextual nuances, manage discrepancies, errors, and generalize well to new inputs (Riedel et al., 2017).

Consistency and stability: Maintaining a consistent and stable scenario vocabulary allows for easier understanding, ensures continuity in assessments, and promotes effective decision-making. Stability in terminology enables long-term assessment of climate change impacts and facilitates the comparison of results across different periods and regions. The IPCC could provide guidance or principles for scenario developers to aim for more intuitive, accessible naming conventions and terminology in the future. While not binding, this could help steer the process.

Coordinated global efforts: Climate change is a global challenge that requires coordinated efforts from multiple stakeholders. Consistent vocabulary facilitates collaboration and knowledge sharing among scientists, policymakers, and organizations worldwide, enhancing the effectiveness of international initiatives and policies aimed at addressing climate change and reporting on climate change risk (e.g., Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures -TCFD or national governments). For example, the financial sector is challenged with reporting on climate-related risks (e.g. recommendations by TCFD) including a high-emission scenario and needs to decide on what scenarios to use while there are not only the IPCC scenarios to choose from but also scenarios developed, for instance, by the International Energy Agency or the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). Similar challenges are encountered by national governments or public and private sectors on scenario selection. Having a set of common or harmonized low, middle and high-end scenarios, would facilitate decision-making and make it more transparent and consistent what economic impacts to expect under future climate change.

Long-term planning: Consistent vocabulary supports long-term planning by governments and other entities. It enables them to develop policies, mitigation strategies, and adaptation plans that align with scientific assessments and projections. Frequent changes in vocabulary disrupt planning processes and introduce unnecessary complexity and uncertainty.

Effective communication: A stable vocabulary enhances effective communication between scientists, policymakers, and the general public. It ensures that key messages and findings are accurately understood and helps avoid misunderstandings that might hinder the implementation of climate change actions. IPCC often invite feedback from key user groups (policymakers, business leaders, etc) on challenges understanding or applying scenarios. This input could inform efforts to improve clarity.

To foster a broader public comprehension, dedicated endeavors toward straightforward, clear communication and illustrative visualizations are essential to clarify the distinctions between scenarios in various reports. Ultimately, maintaining uniformity and precision in terminology is crucial to circumvent potential ambiguities. Addressing this remains a persistent challenge in communication.

The IPCC has changed its scenario terminology several times since 1990, creating challenges for climate change assessment. These frequent changes have led to significant transition costs for updating models, retraining users, and communicating new terms. Furthermore, these changes have inadvertently compromised the comprehensibility and applicability of the IPCC scenarios for policymakers, stakeholders in the financial domain – both public and private – and the general populace. To reduce these transition costs and improve understanding and usability of scenarios, the IPCC should maintain consistent scenario vocabulary across assessment cycles.

By solidifying the terminology post-AR6 and ensuring the unwavering use of RCPs and SSPs at least up to AR7, and possibly in subsequent cycles, the IPCC can shift its focus from terminological updates to the enhancement of scenario quality and interpretation. Instituting a standardized set of scenarios, encompassing low, middle, and high-end trajectories with uniform terminology, would equip policymakers and leaders across public and private sectors with a clearer grasp of climate scenarios. This, in turn, would empower them to make well-informed decisions in the face of climate challenges.

Acknowledgement:

The authors acknowledged Anne-Sophie STEVANCE of International Science Council (ISC) for editorial review role.

University of Hamburg; Chair, RIA Working Group, IRDR.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in our guest blogs are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council