This article is part of the series “Women scientists around the world: strategies for gender equality,” examining the factors that enable or hinder women’s participation in STEM and related fields. This series is informed by a pilot study conducted in collaboration between the International Science Council (ISC) and the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES), based on interviews with women scientists worldwide. The series is published on both the ISC and SCGES websites.

Catherine Jami was raised in a family deeply immersed in science, with both her parents being medical doctors and researchers. In high school, she was fascinated by mathematics and Chinese language and culture. In France, however, academic norms rarely accommodated dual interests and given this context Jami decided to pursue mathematics after she finished high school.

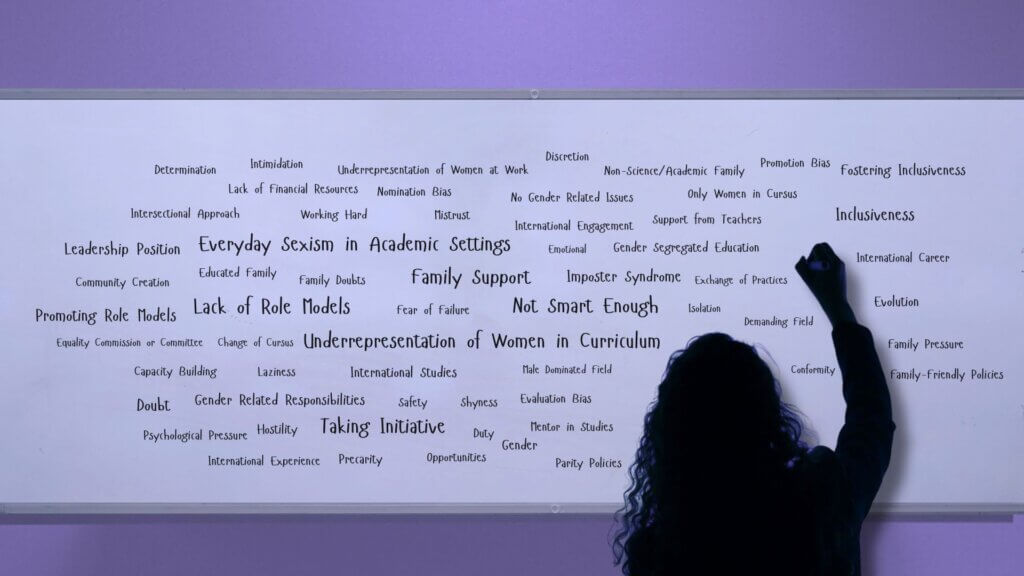

She entered the Classe Préparatoire at the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand, a highly competitive preparatory school for entrance to France’s elite institutions. There, she was one of just three girls in a class of more than forty. “During my first year, I experienced a hell of sexism,” she recalls. Incidents of sexism ranged from boys warning others not to speak to her, to a paper penis placed on her chair and pornographic images stuck on the blackboard, while the teacher conducted a two-hour lesson, smilingly tolerating the degrading visuals, and even joking about them. “This was 1978, not the Middle Ages,” Jami notes, emphasizing the shock she felt on encountering such entrenched attitudes.

These experiences contrasted sharply with her family’s progressive dynamic — where her father shared domestic responsibilities, enabling her mother to build an equally successful career. “I discovered sexism in the ‘real world’ and realized my family was unusual,” she reflects.

In 1980, Jami entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), a prestigious French institution known for producing top academics, at a time when the ENS had separate institutions for men and women, in effect implementing a kind of affirmative action. “This separate entry for women was a kind of compensation for the crushing discouragement of young women from doing science that I had experienced,” says Jami.

A woman professor who was a head of department of the ENS told her female students they were not as bright as the students in the male part of the ENS. “It’s not only men who are sexist,” Jami reflects. Fortunately, a supportive male mentor later helped her pursue a path that would make it possible to merge her love for mathematics with her interest in Chinese language and culture. “I had always wanted to understand why and how mathematics had been invented.”

So, she started to work on the history of mathematical sciences in China. Her PhD research focused on an 18th-century Chinese mathematical work on power series expansions of trigonometric functions. This work, authored by a Mongolian astronomer, discussed formulas discovered in Europe through the use of calculus. However, the Mongolian author proved these formulas without the use of calculus:

A historian does not say, ‘This guy doesn’t know how to check whether a series has a limit, because he doesn’t know calculus.’ If he was to take an exam in France today, he would not pass. But what is interesting is how he proved that the formulas were valid without calculus and thus enabled people in his scientific community to use it. Historians try to understand the people of the past in their own terms. They do not think that people were trying to do what we are doing now in science and failing. What I study is how knowledge is reinterpreted as you shift from one system to another.

Despite scepticism from some of her mathematics tutors, her decision proved prescient, as she successfully obtained postdoctoral fellowships and, in 1991, was appointed to the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

Jami’s involvement in international scientific organizations began when she served as an officer of the International Society for the History of East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (ISHEASTM). The organization was designed to promote the study of East Asian scientific history, a field that had often been overlooked in Western-centric academic circles. Jami became Treasurer and later President of ISHEASTM, when the society became affiliated with the Division of History of Science and Technology (DHST) under the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IUHPST). In 2005, Jami was elected to the DHST Council, serving as treasurer for four years, and then as Secretary General. The latter post involved serving as Secretary General of IUHPST as well for two terms.

One of Jami’s primary goals during her time with IUHPST was to expand membership globally, particularly in underrepresented regions like Africa, South America, and Asia. Following her efforts, a congress was held in Brazil, and another one will be held in New Zealand in 2025, thus further promoting truly global collaboration.

A key aspect of Jami’s philosophy is her commitment to inclusivity, not only in terms of gender equality but also in terms of representation from different regions of the world. It involves ensuring that scholars from all regions of the world, especially those from less-represented areas, have equal access to global scientific networks and are given the opportunity to contribute their knowledge and perspectives. “There is ample evidence that diversity is a condition for making good science,” Jami asserts.

As someone who has worked extensively within international unions, she advocates for a “one country, one vote” system in international scientific organizations, which gives all countries an equal voice, regardless of their size or resources. “The weight of, say, Peru and of the United States is thus the same for most decisions,” she points out.

When Jami heard about the Gender Gap in Science (GGS) project, a collaboration initiated by the International Mathematical Union (IMU) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and funded by the International Science Council (ISC), she eagerly associated her union, the IUHPST, as its Secretary General.

Following the end of the Gender Gap in Science (GGS) project, Jami played a key role in the foundation of the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES). She drafted a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), which was widely welcomed and allowed SCGES to expand from 9 to 25 partner unions. She noted that a significant shift had occurred in the approach to gender equality in science: “My sense is that something historical was happening in the GGS project and continues with SCGES. It is no longer organizations telling scientists what they should do. It is scientists asking themselves, ‘What do we want to do? What can we do? Let’s do it!'”

Jami highlights the crucial role of the social sciences in addressing gender issues and equality, noting that these disciplines with their long-standing focus on gender and inequalities, offer unique insights that are vital to understanding and addressing the complex dynamics of gender in science.

In the Gender Gap in Science (GGS) project, historians of science were the first from a discipline involving social sciences to join the collaboration, pushing an interdisciplinary approach to tackle gender disparities in scientific communities. As chair of the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES), Jami expressed her pleasure in seeing more social science disciplines join the initiative, including anthropology, political science, psychology, and geography. These disciplines, which are already engaged in research on gender issues and various other inequalities, bring a variety of perspectives and methodologies that enhance SCGES’s impact.

One important finding from historical research is that women have always engaged in what is now called scientific activity. One basic challenge lies in their historical “invisibility.” Jami cited the Draw-a-Scientist Test, which has tracked how children envision scientists. When the study began in the 1950s, 90% of the drawings children made following this prompt were of white men. Now, about 70% of children’s drawings depict men; while this shows some progress, Jami thinks the pace of change needs to be sped up significantly.

“Let us be mindful of younger people,” Jami urges. “There is still a lot to do in terms of boosting the self-confidence of young women who are considering a scientific career. And that is really a job for everybody.”

Prof. Catherine Jami is a Research Director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). She has served as Secretary General of the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IUHPST). She was one of the founders of the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES) and its inaugural Chair, from September 2020 to October 2024.

blog

blog

blog

blog

Copyright

This open-access article is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. You are free to use, adapt, distribute, or reproduce the content in other forums, provided you credit the original author(s) or licensor, cite the original publication on the International Science Council website, include the original hyperlink and indicate if changes were made. Any use that does not comply with these terms is not permitted.

Disclaimer

The information, opinions and recommendations presented in our guest blogs are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of the International Science Council