It is hard to imagine the extent that medical physics and engineering have shaped and improved modern healthcare over the last 50 years. Technologies such as X-rays, MRI scans, ultrasound and particle accelerators used in cancer treatment, are all contributions from brilliant medical physicists and engineers and have become vital in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease.

But with intense, lengthy and expensive training programmes needed to succeed, who supports these pioneering individuals themselves, especially those from less privileged backgrounds? The International Union for Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine (IUPESM) was founded in 1980 as the union of the International Organization for Medical Physics (IOMP) and the International Federation of Medical and Biological Engineering (IFMBE) – a platform to support engineers and physicists and the role they play in the provision of healthcare, as well as a forum for presenting the scientific results and major innovations in health-related technologies to the science fraternity. In the four decades since its launch, it has brought together a global network of some 150,000 medical physicists and biomedical engineers in almost 100 countries, dedicated to improving healthcare, with a particular focus on developing countries.

The medical physicists and engineers are like the orchestra in the opera: they are not the people you see, but they are the ones who ensure that the technology needed in healthcare is created and developed. This is the common vision shared by the IUPESM officers Prof James Goh, Prof Slavik Tabakov, Prof Magdalena Stoeva and Prof Leanro Pecchia – themselves highly awarded physicists and engineers.

“The increase in the quality of healthcare and the effectiveness of medical technology usage, lies in adequate education and training for medical physicists and engineers, who are the front-liners when it comes to dealing with technology in healthcare,” says Prof Stoeva.

The medical physicists and engineers are like the orchestra in the opera

Key to its success have been the professional initiatives and support for educational programmes globally. Every other year for the last three decades, young physicists and engineers take part in a month-long bi-annual training programme in Trieste, Italy, with support from Unesco and the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP). Many of these young graduates, given the opportunity to network and learn from leading scientists, have gone on to achieve great things, making a significant impact at a personal, national and global level.

So far the number of alumni from the programme is in excess of 1,000 and the IUPESM wants to bring on more, in particular low- and middle-income countries where there is a shortage of medical physicists and engineers. This shortage will only become more acute, says Prof Stoeva, as contemporary healthcare and the spread of disease present greater challenges – especially for those living in more basic conditions.

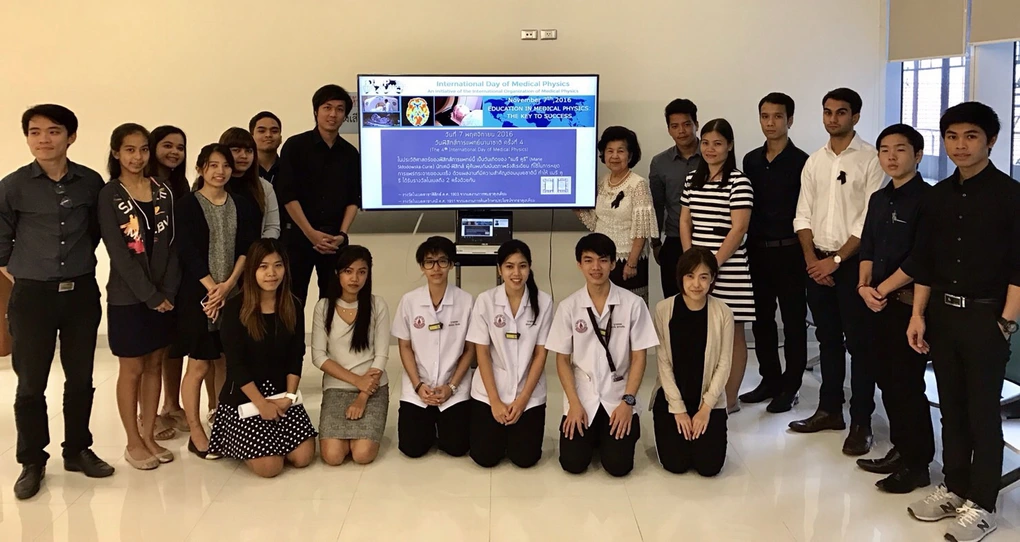

Dr Anchali Krisanachinda, a physicist and an awarded scientist from Thailand, was one of the first trainees of this course. She went on to co-found the South East Asian Federation of Organizations for Medical Physics, training and supporting thousands of young physicists over the last 30 years.

My passion for medical physics keeps on growing day after day –

Dr Francis Hasford

“At the time, [the] education and clinical trainings of medical physics were not well established in Thailand,” Dr Krisanachinda recalls. “In order to further my education, I was fortunate to receive an International Atomic Energy Agency scholarship to continue my study and clinical training in England for two years. Studying abroad during such [a] time was not an easy task due to language barriers and cultural differences.” Despite these challenges, she completed her education and returned to Thailand with a vision to establish medical physics training programmes in her home country.

Upon graduating from her PhD programme in the US, she became one of the first PhD medical physicists in Thailand. “I then established the first graduate programme in medical imaging at Chulalongkorn University Hospital along with founding the medical physics society years later,” she says. “I will dedicate the rest of my life continuing to work as a medical physicist in order to assist our country as well other countries such as Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia and Vietnam to succeed in this field.”

Dr Francis Hasford, meanwhile, an award-winning physicist from Ghana and another beneficiary of an ICTP affiliate programme, was given the accolade of Young Scientist Award in Medical Physics by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics, in 2016.

Now aged 40, he is the vice president of the Federation of African Medical Physics Organization. His 2015 PhD thesis, Ultrasound and PET-CT Image Fusion for Prostate Brachytherapy Image Guidance, was undertaken through an IAEA sandwich fellowship programme between the University of Ghana and the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. The outcome of his research was presented at national and international conferences and was awarded best poster presentation at the Maiden University of Ghana Doctoral Conference.

“I was fortunate to have very good mentors who helped me to do very good work,” he says. “My passion for medical physics keeps on growing day after day. And I have a strong passion in developing other young colleagues in the field of medical physics.”

Another successful alumnus of an IUPESM programme is Myanmar-based Ronald Gyi. In 2011 he was given the opportunity to apply to train at the Biomedical Engineering Society Singapore (BES), which is an IUPESM affiliate, while working for the Ministry of Health in Myanmar. The training took three weeks and was based in Yangon.

“My experience at BES personally changed my career life, and has made a significant impact on developing countries with low and medium income,” he says. “Owing to that training I have upgraded my knowledge in management skills to be able to coordinate training for clinical personnel and to troubleshoot, repair and service medical instrumentation systems.”

Gyi now works for Orbis International, a non-profit based in New York which seeks to eliminate avoidable blindness and restore sight in the developing world. More specifically, he works on the Orbis Flying Eye Hospital – a unique state-of-the-art ophthalmic surgical and training facility based in a converted MD-10 aircraft. Such training, Gyi believes, altered not just his own life trajectory but the work of the doctors involved in the initiative, which has helped countless others.

In the fast moving world of medical technology, it underscores how the right support for talented medical physicists and biomedical engineers can bring positive results well beyond the sum of its parts. Once the playing field is levelled for brilliant minds wherever they are in the world, the possibilities for the next paradigm shift in healthcare could be right around the corner.

This article has been reviewed by Dr Wibool Piyawattanametha, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang & Michigan State University and Robert Lepenies, Karlshochschule International University & Global Young Academy.