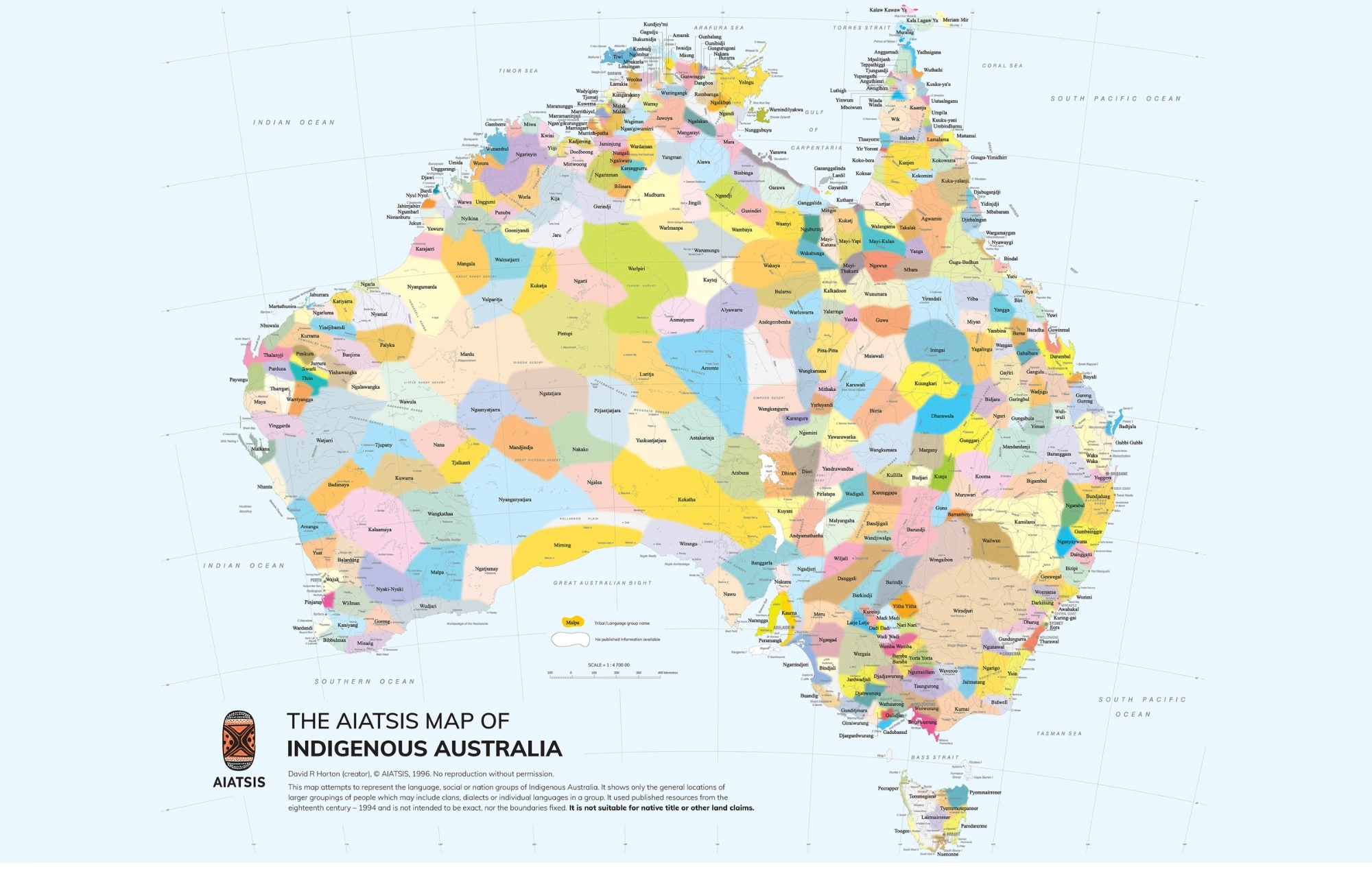

On the continent now known as Australia, there were over 250 First Nations languages and 800 dialects spoken when the British invaded in 1788, but now only 40 languages are still spoken and just 12 are being learnt by children from birth.

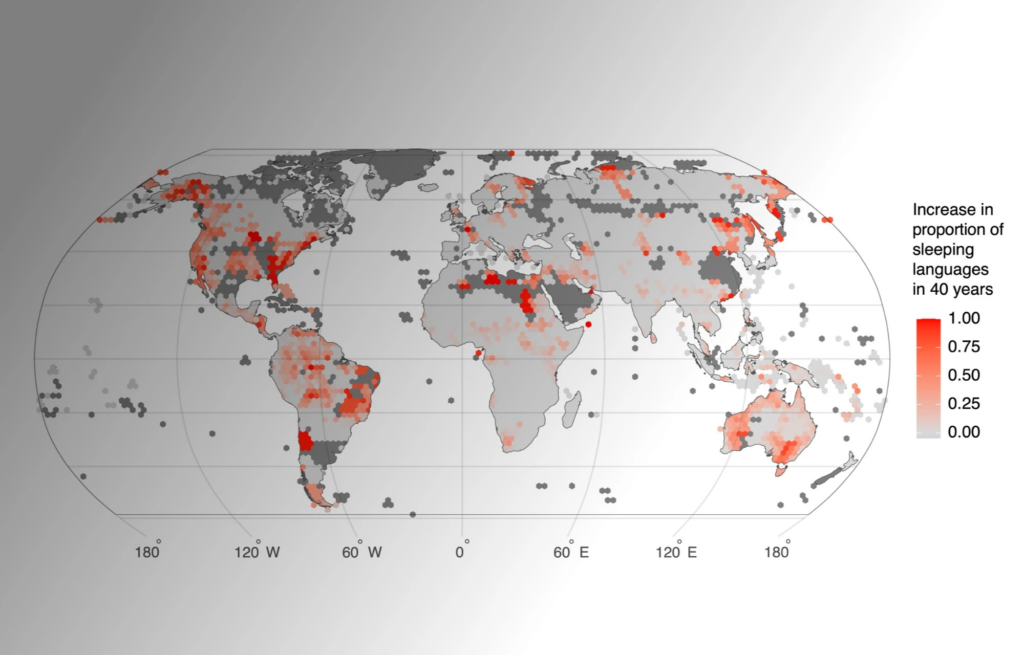

“Of the approximately 7,000 documented languages globally, nearly half are considered endangered,” says Felicity Meakins, a linguist at the University of Queensland and Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.

“Language loss could triple in the next 40 years,” she says in a recent Nature paper. “Without interventions to increase language transmission to younger generations, by the end of the century there could be a nearly five-fold increase in sleeping languages, with at least 1,500 languages ceasing to be spoken.”

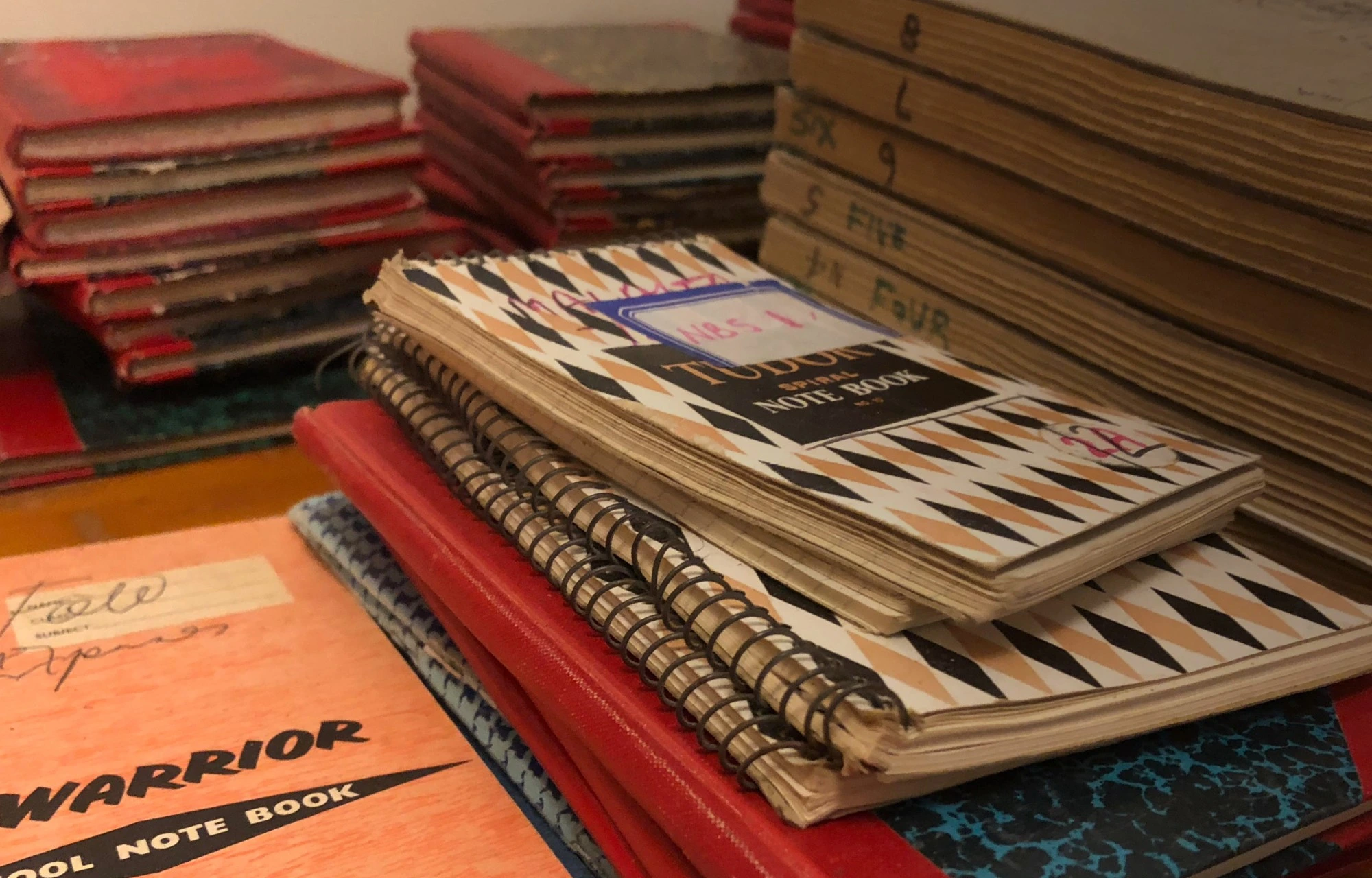

First Nations communities in Australia are working with linguists like Meakins to document their languages by drawing together phrases and words still spoken in families, and analysing scarce historical journals and wordlists recorded by Europeans while the language was still being widely spoken.

However, archival records are not always completely reliable sources. Sometimes, miscommunications between European settlers and First Nations Australians led to inaccurate interpretations. But, with fewer and fewer speakers of Indigenous languages, unpicking these mistakes is becoming increasingly difficult

Larissa Behrendt, a Gamilaraay Yuwaalarray woman, academic, lawyer, writer, filmmaker and Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, explains how early linguistic research falls short of modern standards.

When we lose a language, we can also lose medicine and dietary knowledge, stories of survival through geological, environmental, climate and political change, and traditions orally transmitted over tens of thousands of years.

The Unesco International Decade of Indigenous Languages, which kicks off in 2022, will showcase their relevance to sustainable development and the preservation of biodiversity by maintaining ancient and traditional knowledge that binds humanity with nature.

“[Regeneration of language can not be separated from cultural regeneration and] you see a rebuilding of the social fabric in those communities. It gives people a stronger sense of identity, a stronger sense of self-worth, a stronger sense of community and a stronger sense of pride,” says Behrendt.

“I think that’s a really tangible thing.”

Behrendt’s late father, Paul, only began to explore his First Nations identity in adulthood. He was orphaned at four years old following the death of his mother, who herself was taken from her family as a child under government assimilation policies. Growing up knowing he was Aboriginal, but with no knowledge of his culture or family, he was taught to be ashamed of his Aboriginality.

In the 1980s, Behrendt’s father began searching the archives for his family. He was an intellectual and driven, but without a university education he benefitted from the mentorship of a group of historians.

Having found members of his family, he then went on to unearth thousands of records and record oral histories. He also helped establish Link-Up, a service reconnecting other First Nations families separated by assimilation policies.

“I didn’t need a university degree in psychology to see what a big difference it made,” Behrendt says of her father’s work. “His sense of researching, understanding how important it was to work out how to use the colonial archive, and then also the importance of collecting our oral histories and all the material that’s in that. It was something that I guess instilled in me the importance of research and academia, even though he didn’t have an academic background.”

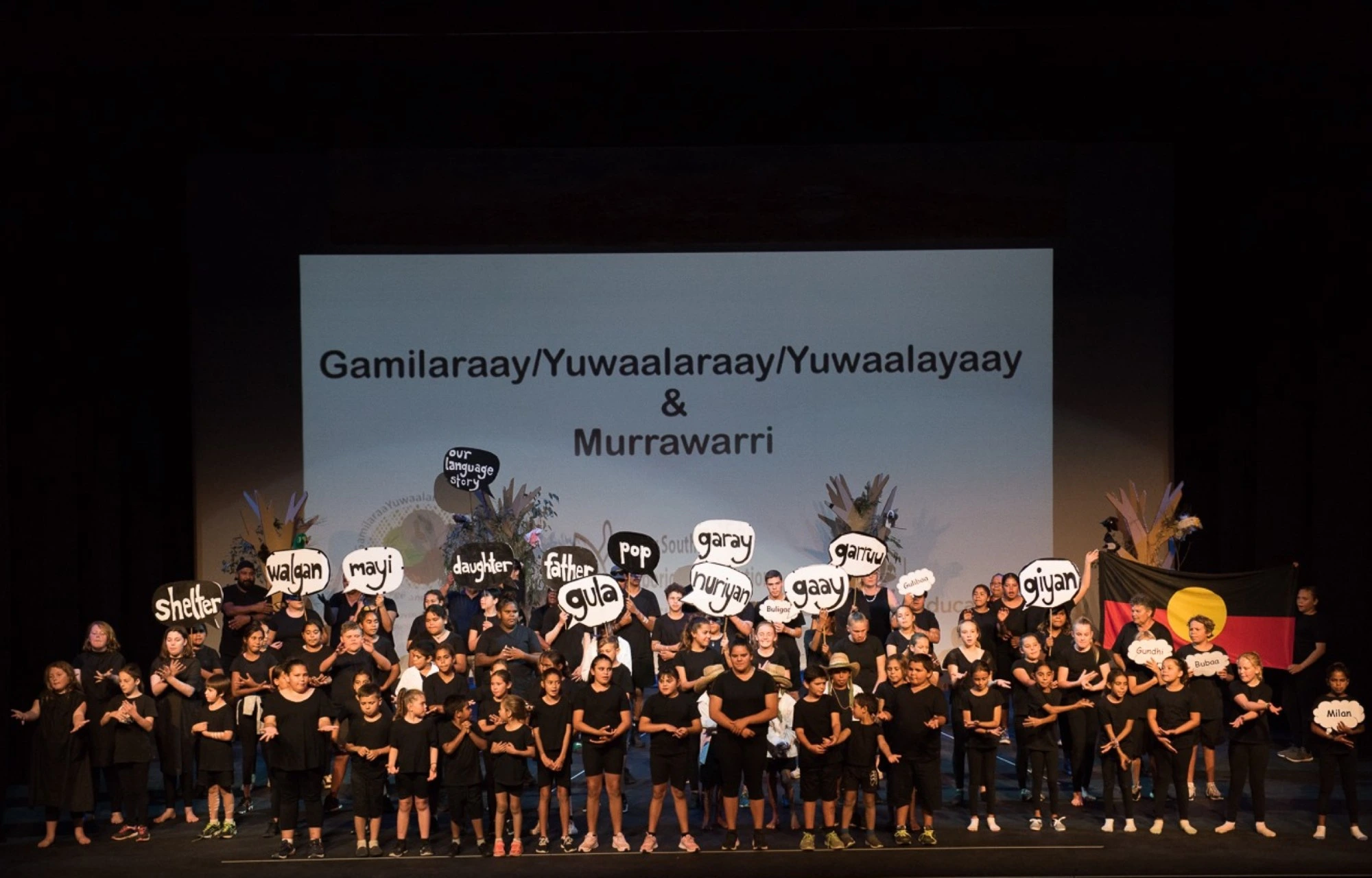

After his death in 2006, boxes upon boxes of his research were donated to the Mitchell Public Library in Sydney, where they continue to be used to reconnect families and revitalise Gamilaraay Yuwaalaraay language and culture in schools and universities.

While the main site of language renewal is in schools and universities, First Nations languages are also finding their expression in the performing and visual arts.

Noongar couple Clint and Kylie Bracknell have recently created a dubbed version of the Bruce Lee classic Fists of Fury, and have reinterpreted Shakespeare’s Macbeth as Hecate, both entirely in Noongar – the language and collective name of the people of the south of Western Australia.

‘Speaking Noongar was a threat to your human rights, your freedom of movement, the right to be the parent to your children [in the early 1900s],” Clint explains. “You more or less had to disassociate yourself from an Aboriginal identity or Aboriginal cultural markers like language. That was the reality for a lot of people, [including] my own family. A lot of stuff just went underground.”

Their language revitalisation work is evoking pride and connection, and he hopes bringing Noongar language to a wider audience will help to dismantle systematic racism.

“We’re not just doing a dance for the public,” says Clint. “We’re doing something that’s actually telling a deeper story about who we all are and what we still have that has never gone away.”

“Especially with Hecate, there was this real need to show the cast as – ‘these are Noongar people that you might pass in the street’. Think twice, you don’t know the depth of a person, don’t judge people, till you think about the full length of their story and how that story can go back to the ancestors and right back to Country. It’s about humanity.”

“It’s healing, we’re regenerating, getting it back now” – Sonja Carmichael

Quandamooka artists Sonja and Leecee Carmichael, from Minjerribah (an island near Brisbane off the coast of Queensland) incorporate First Nations words and phrases into their work that draw together family, Country and weaving.

The mother and daughter duo weave words in Jandai that now stand loud and proud on the walls of prestigious exhibitions including Tarnanthi and the NATSIAA.

Sonja explains that Aboriginal missions, which were in operation until midway though the last century forbade cultural practice, including using the language.

“The Aunties recall the Grannies hiding to whisper in language.”

The Myora mission on Minjerribah was closed in 1941.

Wordlists and woven baskets held in anthropological collections are now accessible to their rightful owners and are being used to spearhead a cultural and linguistic resurgence.

“It’s healing, we’re regenerating, getting it back now,” explains Sonja referring to both language and weaving.

In 2011 the first Jandai dictionary was published. Now, school children on Minjerribah learn Jandai, and it is promoted through workshops and the annual Quandamooka Festival where songs and poetry have been written and performed in Jandai, and story books written.

Sonja and Leecee say they know very little Jandai, but once they get talking it’s obvious they know plenty of words and phrases. Obvious also, is an absolute resilience, joy and pride when they speak their language.

“There’s a lot of exciting work happening, for us it’s so meaningful to be able to use our words and honour our Elders and connect words with Country,” Sonja says.

“It makes me feel strong, it makes me feel proud, it makes me feel honoured to be a proud Quandamooka woman”.

“First Nations languages are as fragile as the Elders who carry them” – Felicity Meakins

Meanwhile, in the remote community of Kalkaringi, the Gurindji people have been collaborating with linguists for nearly 50 years to document their language.

Their traditional language, Gurindji is still spoken by Elders while those under 50 mainly speak Gurundji Kriol – a mix of traditional Gurindji and Kriol, an English-based Creole language brought by colonists in the early cattle station days.

In 1966, Gurindji stockman Vincent Lingiari led 200 pastoral workers in strike protesting appalling human rights abuses, in what is known as the Wave Hill Walk Off.

It is a strong legacy, as is their dedicated and detailed documentation of their language, songs and sign language, including a dictionary, grammar, oral histories, children’s books and posters.

“It makes us really proud. Us younger generations can see what our Elders have done,” says Lisa Smiler, who is the granddaughter of Vincent Lingiari. “It is important to keep the old language to stay connected to our ancestors.”

Meakins, who has worked with Gurindji people for two decades, most recently through the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, credits them for training her to be an “ethical linguist”. She is trusted in their community, works collaboratively and is passionate about preserving languages for speakers and beyond.

“Non-Indigenous Australia has little appreciation of the genius of Indigenous languages, what they mean for the health and wellbeing of speakers, how they reflect identity, social dynamics and the world,” says Meakins. “The silencing of languages has just been absolutely devastating.”

First Nations languages encode highly complex kinship systems, navigational systems, weather behaviour and spatial awareness that requires a deep connection and understanding of Country and kin.

“For example, European languages have egocentric systems of expressing the position of objects in space that are mapped from the body. We think in terms of objects being to the left or right of ourselves,” she says. “Whereas spatial systems in [First Nations] grammars are expressed according to a person’s location in their Country. Languages like Gurindji that have 24 different ways of saying ‘north’ which is extraordinary.”

“It’s easy to be complacent in places where people still speak their languages. But the situation is just so precarious. These languages and their associated knowledge systems are as fragile and precious as the Elders that carry them.”

But as Cassandra Algy, who has collaborated with Meakins for nearly two decades notes, “The dictionaries, grammars and books we’ve made are so important. It feels like our ancestors are still with us”.

Paid and presented by the International Science Council.

This article has been reviewed for the International Science Council by Binyam Sisay Mendisu (Ph.D), Associate Professor of African Languages & Linguistics, The Africa Institute, Sharjah, UAE and Genner Llanes-Ortiz, Assistant professor of Indigenous Studies at Bishop’s University, Canada.

By Jillian Mundy