This article is shared as part of the ISC’s new series, Transform21, which will explore the state of knowledge and action, five years on from the Paris Agreement and in a pivotal year for action on sustainable development. This piece was first published in the Scottish Review on 26 May 2021.

It’s difficult to start any narrative these days without reference to the COVID-19 pandemic. It pervades conversations, societies and our uncertainties about the future. Economists think of it as an ‘externality’, like a cometary impact, unpredictable and without human cause. But pandemics and civilisation go together. There are, and were, no pandemics amongst dispersed un-urbanised populations. Increasing human penetration of wild spaces, with novel viral diseases always on the lookout to jump the species barrier, coupled with the growth of jostling urban centres of civilisation that readily spread infection, have proved a fertile combination for generating pandemics. And they are frequent in recorded history; about three per century. So why are we taken by surprise when they turn up?

‘The risk of human pandemic disease remains one of the highest we face,’ stated the UK Government’s 2010 national security strategy. The ‘possible impacts of a future pandemic could be that up to one half of the UK population becomes infected, resulting in between 50,000 and 750,000 deaths in the UK,’ which has turned out, so far, not to be a bad estimate. In 2017, the UK national security advisor noted that the likelihood of ’emerging infectious disease’ had increased since 2010. In short, we knew this would happen. Why, then, were we not prepared?

Claiming something is a priority doesn’t really matter if no-one believes it really is. And that was the problem. For UK Governments, the risk of a pandemic was too obscure, too hard to imagine. But we can’t simply argue this was a failure of government. With few exceptions, no-one else raised the warning flag. It was a failure of imagination, and of memory, on all our parts.

The pandemic has been a stress tests for governments. Some had learned from SARS in 2003 and were ready. Taiwan, Vietnam, Singapore, Laos. Some had it high on their national risk registers, they knew it would happen, but still weren’t ready. We did not lack knowledge, we just didn’t apply it.

The catch-up has been remarkable but not because of the actions of governments in ‘following the science’, which has been hesitant and often misplaced. It has been because of the solidarity and the orderly and responsible behaviour of citizens and the remarkable and spontaneous response of the global scientific community, with unprecedented sharing of ideas and data within and beyond the community and across the public-private interface. This agility has been essential in enabling progress from initial sequencing to effective vaccines in less than a year. In the words of the director of the US National Institutes of Health: ‘we have never seen anything like this’; ‘the phenomenal effort will change science – and scientists – for ever’.

In the UK, success in rolling out the vaccine seems to have led to complacency about the longer-term, with the implicit assumption that the pandemic can be controlled within our borders. Our governments may be in danger of showing the same unwillingness to take scientific perspectives about possible COVID end-games seriously that they showed prior to and in the early stage of the pandemic.

Earlier this year, a number of us argued in the pages of The Lancet journal that a nationalistic rather than global approach to vaccine delivery is not only morally wrong but will also delay any return to a level of ‘normality’ (including relaxed border controls) because no country can be safe until all are safe. The SARS-CoV-2 virus could continue to mutate in ways that both accelerate virus transmission and reduce vaccine effectiveness, with the decisions of global agencies, governments, and citizens in every society greatly affecting the journey ahead for all.

There is an optimistic scenario that, although COVID-19 will remain endemic in the global population, new-generation vaccines will be effective against all variants (including those that may yet emerge), provided that procedures to control spread of the virus are pursued effectively in every country in a coordinated effort to achieve global control. Even with international cooperation and adequate funding, this scenario would inevitably take a long time to achieve.

At the other extreme is a pessimistic scenario, in which SARS-CoV-2 variants emerge repeatedly, with the ability to escape vaccine immunity. In this scenario, only high-income countries can respond by rapidly manufacturing adapted vaccines for multiple rounds of population re-immunisation in pursuit of national control. The rest of the world then struggles with repeated waves and with vaccines that are not sufficiently effective against newly circulating viral variants. In such a scenario, there would probably be repeated outbreaks, even in high-income countries, and the path to ‘normality’ in society and business would be much longer.

There has also been a stress test for the geopolitical collaboration that will ultimately determine which of these pathways are taken. So far, governments have failed the test. As the editor of The Lancet, Richard Horton, wrote recently: ‘the human family seems to care so little for itself that we were unable to pool our experience, our understanding, and our knowledge to forge a common and coordinated response’.

The COVID crisis may be the first time that the nations of a globalised world have directly competed for the same limited resources, being tempted to protect their own citizens at no matter what cost to others. Unless, even at this late stage, there is a rediscovery not only of our common humanity but that self-interest demands global collaboration, we may be veering towards the worst rather than the best case scenario.

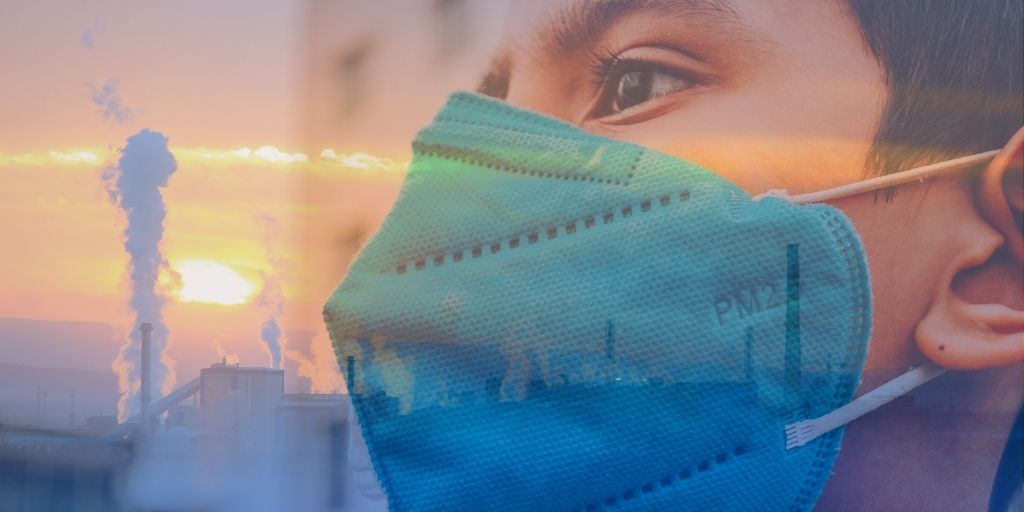

The pandemic, though devastating, may well have proved timely as a lesson in facing the other looming, larger and more fundamental global crisis, that of climate change. We live in a world interconnected not only by travel but by wind, water and weather. The local infects the global and the global determines the local. COVID and climate share a pattern in which the most serious harms have fallen on populations where poverty, insecurity and inequality are endemic and whose lives and livelihoods are inherently vulnerable. Neither COVID nor climate carry passports. Both have long incubation periods, during which their dangers, and the warning voices of experts, are easily ignored.

For COVID, the grim consequences of missing the early warning calls for action have been exposed in several deadly waves of explosive, exponential growth. Climate change has a slower and more complex tempo. Its long-term forecasts, derived from mathematical models, are hard for the public and policymakers to grasp as they challenge intuition and short-term thinking. We live in a world where we are used to the helter-skelter pace of technological change but we are mostly oblivious to the slower, ultimately more powerful stirrings of angry nature, and to the remorseless onset of major climate changes such as the planet has not known for 10,000 years.

The lessons are clear. We must correct the failure of memory and imagination that ignores the workings of nature. After all, they are better understood than the workings of society. Ignoring scientific calls for early action ends up being costlier in the long-run, even if such measures appear initially punitive. Just as for COVID, control becomes difficult when the virus has reached a certain level in the population, so for climate, that has the potential for rapid, irreversible and unforeseeable change as the globe warms beyond critical thresholds. The irony is that successful early preventative actions are likely to be considered wasteful once risks have been averted, throwing into doubt the magnitude of the original risk.

There is, however, one fundamental difference between COVID and climate. There is no last-minute reprieve: no vaccine for the climate risk, unless we foolishly pin our hopes on the advent of some as yet non-existent and untried technology.

So, let’s just make sure we don’t learn the wrong lesson from COVID. It’s not just a public health emergency. It’s something bigger. We are in the midst of one of the biggest global wake-up calls in history, threatening both individual lives and entire economic and social systems. It’s nature telling us that the new global ecology that we have created through our ravaging of Earth’s resources holds great risks for humanity. It’s telling us that local impacts of our actions are transmitted through the global ocean, the global atmosphere and through global cultural, economic, trade and travel networks to become global impacts. It’s telling us that national solutions alone are quite inadequate, that we must resolve the underlying causes of our vulnerability through global collaboration, revitalised global institutions and by investment in global public goods. It’s telling us just how big the externalities are that conventional markets cannot resolve.

However, it’s also telling us that we have the much of the knowledge and expertise to address these problems. What is needed is political will. Let’s hope that Glasgow 2021 provides it.

Geoffrey Boulton is a member of the ISC Governing Board.