Based on the Occasional Paper commissioned as part of the project “The future of scientific publishing”

Regulating digital markets has been notoriously difficult. The traditional anti-trust measures are ill-suited for a fast-moving, constantly changing digital environment. Assessing the long-term consequences of new products and acquisitions is extremely difficult in digital markets, and by the time an action is taken, the whole industry has moved on.

In this sense, regulating a digital scholarly publishing market, dominated by a small number of big players, has not been much different. When the industry went digital, it was hard to maintain a level playing field for all publishers and prevent anti-competitive behaviour. If anything, a costly transition to digital tipped the scales against smaller non-profit publishers with limited access to capital.

What can the scientific community do to correct the power disbalance, which suppresses healthy competition on the market and, therefore, stifles innovation? Gatti walks us through the major business models, starting from the 20th century, deconstructing their incentives and driving forces, and highlighting possible points of intervention.

Throughout the 20th century, the dominant model was “reader-pays”, which disadvantaged many individuals and institutions that could not afford subscription costs, but ensured a steady income for publishers with strong brands.

Having limited information prior to purchasing a product – in this case, a scientific publication – readers have to rely on other indicators to judge a product’s quality – mostly using a journal’s authority and reputation as a proxy. In an already disbalanced market with a small number of big dominant publishers, such a model only boosts the strength of the few.

An “author-pays” model has emerged as a popular alternative for open access publications. While allowing for a more widespread access for all readers, it is hardly an equalizing solution. Now the authors, as opposed to readers, face restrictions and inequality. In less well funded institutions, this may dramatically change the relative treatment of researchers, as only selected few are able to get their work published in prestigious journals. It is clear that this then has a further impact on researchers’ careers and future funding opportunities.

In this model, branding remains critically important, as it allows bigger publishers to charge higher fees. A publisher’s peer-review process – which typically depends on unpaid work by other scientific researchers – still serves as a quality assurance and is used for judging research value.

As long as journals’ brands are associated with perceived research quality, authors have little choice but to participate in and sustain this system which creates high profit margins for the top publishers.

There is a long history of universities and other institutions directly or indirectly supporting publishing operations – often through the creation of university presses – but also by offering enabling technologies, such as technical infrastructure for open access journals.

Although new technologies allow for dramatic cost reductions, they require substantive initial investments that are available only to bigger actors with easier access to capital. Here is where institutions can step in and lower that entry barrier by offering enabling infrastructures.

Finally, institutions can directly fund their own publishing outlets, thereby assuming all associated costs and making access free for everyone.

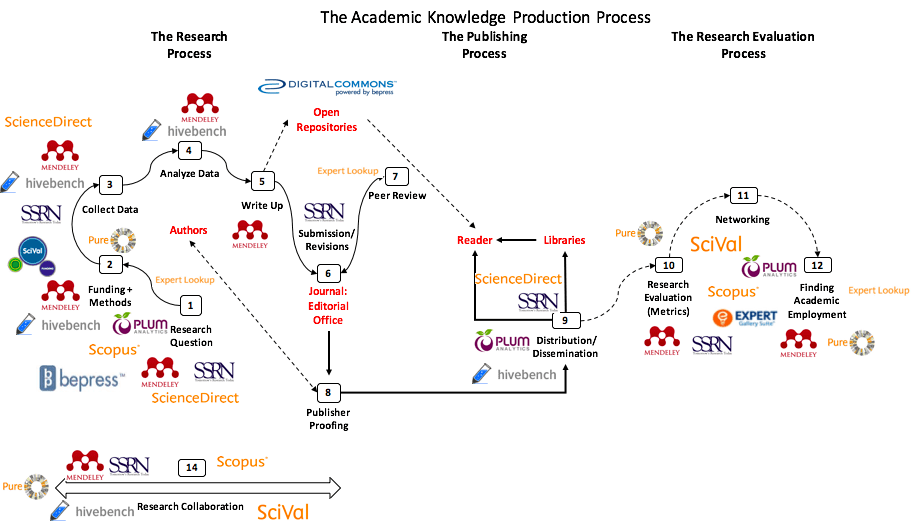

Publishers can also capitalize on services around other parts of the research life-cycle. By creating technical dependencies and locking offered products in bundles (‘big deals’, as they are typically called), publishers secure steady profits. To guard against disruptions, publishers actively acquire newly trending products and solutions in their early stages and integrate them into their own service.

To mitigate any technical dependencies that would tie users to specific services, there must be interoperability between competing systems.

Finally, usage data is a lucrative commercial product in itself. Frequent users of publishing platforms may, in fact, present a higher value to publishers than the actual content. Google and its likes have been successfully employing this model by offering helpful services for free and, in return, selling access to its users and data to advertisers. Publishers with unique, valuable content are well positioned to copy this model.

There are already some instances of using such data for comparative assessment of research. While the assessment measure itself might be good, the prospects of delegating such an important function in the scientific life-cycle to a commercial entity should be carefully deliberated by the scholarly community.

The models described above have serious implications for the publishing sector, raising important concerns and calling for serious rethinking of business as usual in the scientific publishing sector. Gatti calls on the international scholarly community to take a leadership role in establishing appropriate standards and norms internationally, as national anti-trust authorities are unlikely to exert the needed pressure.

Recommendations for other digital markets can serve as useful roadmaps for scientific publishing. A recent report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel for the UK Treasury, for example, emphasizes the need to limit anti-competitive actions by the biggest platforms and to reduce structural barriers that hinder competition:

“Active efforts should also make it easier for consumers to move their data across digital services, to build systems around open standards, and to make data available for competitors, offering benefits to consumers and also facilitating the entry of new businesses.”

The report also recommends the establishment of a national “digital markets unit” to overlook ongoing developments, coordinate action, and encourage “good behaviour”. Although lacking the legal weight of national anti-trust agencies, such a body could still be a powerful force through its representation of the broader scholarly community.

Alternatively, the scientific community can directly support the development of open scholarly research and publishing infrastructures, alongside commercial platforms, and, therefore, sustain independent research.

Considerable resources will have to be drawn, but, with a coordinated international action, a more diverse, competitive, inclusive scholarly publishing market is still within reach.