Although global emphasis is on travel, cities are at the frontline of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) disease, and are critical to understanding what drives exposure to the virus, what its impacts will be, and – crucially – how to confront the pandemic. In Hubei province in China, most of the infections are centred in its capital city, Wuhan, where the outbreak is believed to have begun at a seafood market for urban foodies. Cases in Italy emerged from the Lombardy region, whose capital is Milan, a global hub of fashion and finance, and cities in Tuscany, Liguria and Sicily have reported new infections. In South Korea, the capital city of Seoul has embarked on a large-scale coronavirus testing drive. It seems therefore fair to argue that as COVID-19 continues to spread, many of the impacts – and opportunities for learning and responding effectively – are likely to be concentrated in cities. However, the effects of the virus, and measures for responding, are likely to be different in African cities, due to contextual features which have not yet been given much attention in the scientific and societal discussions about the pandemic.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), frequent and proper hand hygiene is one of the most important measures that can be used to prevent infection with the COVID-19 virus. Public health messages over radio, television and the internet are that we need to wash our hands at least for 20 seconds. But in a typical African city, where densely populated slums or informal settlements are most dominant, water for frequent hand-washing is in short supply – let alone 20 seconds worth – and households often spend 30 minutes or more sourcing water from springs, communal piped water points, swamps or through rain-water harvesting. Water has to be used sparingly for other hygiene purposes, including cleaning shared sanitation facilities, where shared keys to the toilet provide access for multiple households. On-site sanitation facilities such as pit-latrines and septic tanks often already present a risk of contaminating the water available to households, especially when such facilities are unsafely emptied directly into the environment, sending untreated sludge into natural waterways and impacting a city’s main sources of clean water. This and other factors may inhibit the efficacy of hand-washing solutions to COVID-19. Effective measures that match the constraints of the local context in African cities may call for innovative use of urban natural assets for water access (such as springs and swamps), and partnerships that create a safe and affordable system for sourcing clean water using locally-made water pumps.

Land travel, which has been reported to be a likely route of introduction and spread of COVID-19, dominates metropolitan and neighbourhood transport in the cities of Africa. This is signalled by the ever-increasing number of minibuses and motorcycles that have come in to address the deficiencies of state-managed urban transport systems. While minibuses and motorcycles have offered transport advantages in the form of easy manoeuvrability, ability to travel on poor roads and customer responsiveness, the exponential growth of commercial motorcycle services in African cities cannot be conducive to the implementation of social distancing measures that are being encouraged globally to control the spread of COVID-19. When this is coupled with increases in local air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions associated with motorcycle use, the reported cases in Africa and urban residents in general are likely to be exposed to different risks.

| Country | Total Confirmed Cases |

| Egypt | 67 |

| Algeria | 25 |

| South Africa | 13 |

| Tunisia | 6 |

| Senegal | 4 |

| Morocco | 5 |

| Burkina Faso | 2 |

| Cameroon | 2 |

| Nigeria | 2 |

| D.R. Congo | 1 |

| Togo | 1 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1 |

Last updated: March 12, 2020 at 11:00 a.m. ET.

Source: World Health Organization, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 52.

In addition, intra-metropolitan, home-to-work and neighbourhood travel is typically not via well-documented and trackable transport systems that would make it easy to install surveillance systems and enforce travel bans and quarantines in the same way that’s been seen in some cities of the global North and developed south. Rather, on and off-peak travel in urban Africa is heavily characterized by commuting on foot, followed by the use of omnibuses and motorcycles that are seldom required to track customers. In Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where one COVID-19 case has been reported, an estimated 60 to 80 percent of the 10 million residents travel on foot. Residents of Nairobi’s slums are twice as likely to walk to work rather than travel by automobile. In Lomé, the capital of Togo, where another COVID-19 case has been reported, the use of at least two transport modes in the course of a single trip is common, with motorbike taxis shuttling city-dwellers to workplaces in which working conditions may be arduous, adding to the urban health burden. Besides, travelling to rapid response units or local health centres can be a nightmare in a typical African city, with competition and congestion along the carriage way, limited public transport options that offer safety from public health hazards, heavy reliance on person-to-person information on where services are located, and ineffective navigation aids.

Mobility solutions such as Uber Taxis, SafeBoda in Kampala, and tuk-tuk rides in Cairo, Addis Ababa, Banjul and other African cities, may help address connectivity, the transmission of COVID-19 and other public health hazards, especially amongst city dwellers that are digitally literate and can afford the costs associated with the use of smart-mobility strategies. However, links between the adoption of smart-mobility technologies and public health systems are underdeveloped in urban Africa. Although such a linkage would bring together data on travellers’ personal details, health status and location of nearest health unit in a way that could help control the spread of COVID-19, there have been no collaborative efforts between policy-makers, public health experts and smart-mobility service providers in Africa to leverage such possibilities. This partly explains why COVID-19 online resources and updates by ride-hailing providers such as Uber, or online fast-food companies such as Jumia Food in Kampala-Uganda, on supporting drivers or delivery persons who are diagnosed with COVID-19, may have limited impact in a typical African city setting.

The other technological advancement worth mentioning is the mobile phone. Mobile internet connectivity has gained ground sporadically, and has more penetration in certain populations than others. For example, Kenya’s rate of mobile internet users is at 83% and similar trends have been observed in Nigeria. However, South Sudan has not yet made significant moves toward mass adoption of mobile Internet. The highs and lows of penetration rates, however, present an opportunity for COVID-19 tech that educates the public through the use of USSD Codes, which can enable mobile phone owners without internet access to check and exchange information about exposure and testing for COVID-19, including in local dialects. Mobile money operating platforms can also be of good use. The value of mobile financial transactions in Africa that have grown over 890% since 2011 and shows no signs of slowing down. It is time for the African telecom and public health sectors to work together to transcend peer-to-peer and merchant transactions to services that can help address COVID-19 and other societal challenges. While there is a delicate balance between privacy and security, an app called Alipay Health Code has been used in over 200 cities in China to assign individuals the colour green, yellow or red, to identify potential virus carriers, and control permission into public spaces. Tencent, the company behind popular messaging app WeChat, has launched a similar QR-code-based tracking feature. Although these developments have been critiqued as measures of automated social control, M-PESA, which covers over 96% of the households in Nairobi-Kenya, and MTN Mobile Money in Kampala, Lagos and other cities, can provide the means to experiment and opportunities for collaborative learning.

Smart phones have also been used to digitally map access to service provision in Africa’s urban informal settlements, and this could be scaled up for use in monitoring and reporting progress on COVID-19. The illegal and unplanned status of informal settlements can undermine the use of physical and electronic means of collecting data and the implementation of measures for response to COVID-19. Due to the lack of geo-referencing codes for properties, streets and neighbourhood paths, data cannot be easily disaggregated according to location and socio-economic backgrounds of individuals, especially for public health purposes. This means that numerical models for COVID-19 inventories, which in the global north have used traffic statistics and property location data to effect quarantines, may not necessarily work to develop preparedness and response plans in African cities. This also brings to bear the limitation of epidemiological models in predicting spread in urban slum populations, where national data about such slums is often lacking or cannot be differentiated along spatial, gender, health history and income level. Such numerical predictions would also require disaggregation of data not only along differences in sub-regions but also in urban ecology. What’s more, in many cases data remains inaccessible for reasons that may have to do with intellectual property rights or geo-political factors. COVID-19 has come at a time when the health data space in Africa is facing a number of challenges that limit the capability for effective response. It is worth exploring the interdependencies between traditional epidemiological data collection systems (such as infections reported at a health unit), the use of spatial media technologies for digitally mapping informal settlements, and smart phones for visual content.

African cities are home to mobile residents pursuing different livelihood options, which are part and parcel of the functioning of interconnected urban systems, including transport, food, water, security, energy, health, sanitation, waste management and housing systems. For instance, in Mathare-Nairobi and Bwaise III parish-Kampala, youth and women have developed alternative economic strategies in the informal waste management sector. Waste is turned into briquettes that are sold as an alternative cooking energy, which often subsidizes household energy budgets, reduces illegal waste dumping in settlements, supports the re-use of waste water, provides cleaner ambient air and contributes to wage employment opportunities – either for contracted employees or piece-rate waste pickers. Waste dealers also own restaurants and other small-scale businesses in their neighbourhoods to square their household expenditures. Other enterprises in African cities, especially in informal settlements, are unincorporated non-farm businesses owned and operated by family members, or individuals from the same village, tribe, ethnicity or religion. These factors influence how social bonds, bridges and links establish forms of reciprocity and trust in socio-economic relations and in the use of transportation, public health and urban systems. Dissemination of public health messages on COVID-19 for example, may depend on word-of-mouth and community dialogues rather than radio and the internet. Control efforts built on containment and reductions in movement may therefore be difficult to implement, especially if they constrain social interactions amongst businesses in the urban informal sector, which contributes more than 66% of total employment in sub-Saharan Africa.

Public health restrictions on movement may be perceived as a punitive measure by the state and can constrain services for informal settlements. The lessons from the Ebola Outbreak of 2014/15 indicated that quarantines, which were used as response measure in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, resulted in large waste disposal needs and other water, sanitation and hygiene vulnerabilities that put a strain on the governance and delivery of services. At one point in Freetown-Liberia, nearly 50% of the population was under quarantine. This meant a huge number of households in often logistically challenging areas required food and water transported to them, coupled with flush floods that made local paths impassable. While they may help contain the spread of COVID-19, quarantines and isolation techniques that depend on demarcated borders between residential and commercial properties can be difficult to implement in urban informal settlements where borderless residential compounds and shared sanitation facilities are the norm. Dwellings are also usually characterized by large families, in which women and the elderly are expected to take care of the sick, as men move in and out of the home to provide for other household members. In a traditional African setting, this distribution of household gender roles can make residents resent isolation mechanisms that distance them from their relatives and spouses or children, and might create resistance, by for example abandoning reporting to local health units for testing and treatment. To address this, community engagement dialogues will be essential, targeting opinion leaders in neighbourhoods to deliver trusted messages on COVID-19, in collaboration with local health workers, religious and cultural leaders, landlords and landladies as well as civil society, political and business representatives. However, community-led surveillance and monitoring mechanisms require a high degree of coordination between urban sectors, which is still a challenge in Africa. The ability of municipal actors to establish an effective monitoring mechanism for health policy implementation and supervision, has for long been constrained by a culture of working in silos. There is also a divide between scientific and non-scientific knowledge and responses to urban health crises, and effective co-generation of knowledge and transmission of good practices is hampered by institutional factors, such as lack of effective reward structures for public health agents, and more practical barriers, such as lack of common definitions for COVID-19 using local dialects vs. the English versions. This can be overcome by through openness to different societal and scientific view points on exposure, response and recovery strategies.

Tackling COVID-19 in African cities will not just be about getting the collection of epidemiological data and use of social distancing techniques right, it is also about grappling with the underlying social, economic and political drivers that are harboured by the sparsely-built and agile nature of informal settlements as well as challenges in the governance of urban systems. Since COVID-19 pays no attention to disciplinary boundaries or departmental units within the city authority or ministry, governance of this global pandemic calls for a process that brings together diverse departments, disciplines and actors to identify appropriate measures for preparedness, response, and recovery.

Buyana Kareem is a researcher at the Urban Action Lab of Makerere University Uganda. He earned his PhD in urban and international development studies from Stanford University, California USA. He has been supported by the International Science Council, under Leading Integrated Research on Agenda 2030 (LIRA 2030), to undertake solution-oriented research on energy and health sustainability challenges in the cities of Kampala and Nairobi. Kareem has consulted with the United Nations Development Programme on crisis prevention and recovery in Mozambique, Gambia and Lesotho.

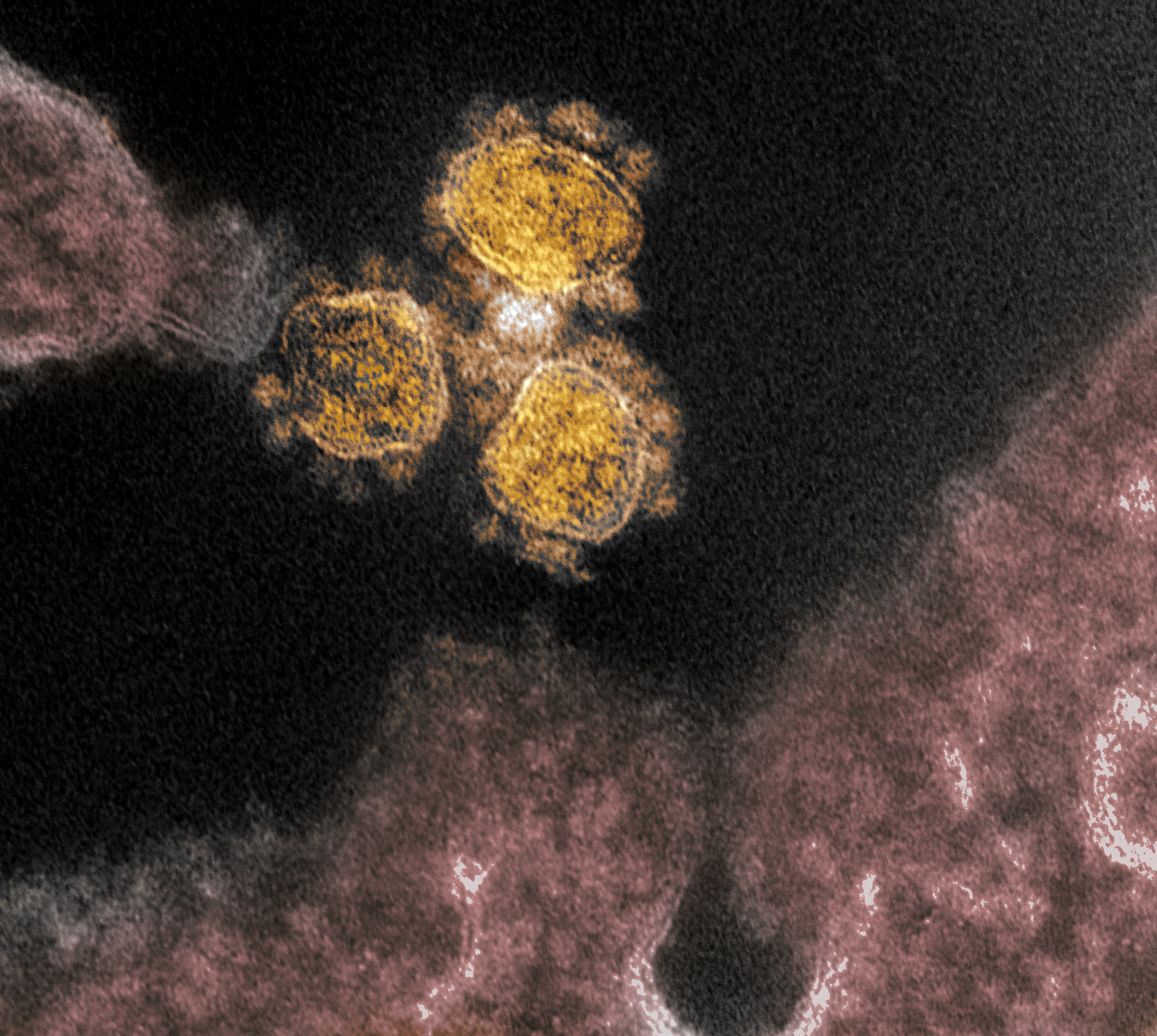

Photo: Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases via Flickr).