In this short blog, Craig Callender*, who is a member of our Committee for Freedom and Responsibility in Science (CFRS), reacts to the recent report of the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing.

In November 2018 the world was stunned when He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies who he had genetically engineered to be resistant to HIV. This announcement triggered a nearly universal condemnation of the procedure. The consensus opinion is that Professor He had violated important scientific and ethical norms. The procedure was not viewed as medically necessary and certainly not worth the risks to the children given our current knowledge and technology. While denouncing his actions, many groups also called for guidance in evaluating potential clinical applications of human germline genome editing.

In response, the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and the Royal Society of the U.K., in consultation with medical experts around the globe, formed the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing. Chaired by distinguished geneticists Kay E. Davies, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Oxford, and Richard P. Lifton, President of the Rockefeller University, the 18-member Commission deliberated for more than a year. In September 2020 their long-awaited report, Heritable Human Genome Editing (HHGE), was released.

National Academy of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, and the Royal Society. 2020. Heritable Human Genome Editing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25665.

Human germline editing is the process of modifying the genome of eggs, sperm or an embryo. Such modification can create a heritable genetic alteration, so it raises many significant issues. The prospect of designer babies, unequal access to this technology, and its impact on society have long raised ethical, religious and societal questions. Some have wondered whether other methods, such as preimplantation genetic testing, already satisfy the medical needs without engaging in HHGE. The report tries to bracket these questions as much as possible, leaving them to a forthcoming report by the World Health Organization (WHO). Instead, the report of the Commission focuses on delineating a safe staged pathway from research to clinical application in the event that a country decides to pursue HHGE.

In rich scientific detail the report describes a “responsible translational pathway” forward. It maps out six hierarchical levels of HHGE use. Each level demands increased rationale to be worth the associated risk, and the report details what is necessary to pass each threshold. The first level to consider in the near term, it says, are applications of HHGE to serious monogenic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, thalassemia, sickle cell anemia, and Tay-Sachs disease. The last level includes the controversial application HHGE to genetically enhance children, such as making them taller or resistant to disease.

The message is clear: safety issues alone preclude HHGE at the present time. Science is not yet ready to engage in even the first stage of HHGE applications. As Jennifer Doudna, a 2020 Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry, comments:

The HHGE report underscores what most researchers in this field are aware of and agree upon: There must not be any use of germline editing for clinical purposes at this time.

Jennifer Doudna (The CRISPR Journal, October 2020)

Our knowledge and technology is insufficient in the near term to guarantee the safeguards we would normally expect of any clinical application. No moratorium on HHGE is advocated. But given the prominence and clarity of the report, no scientist working on HHGE can claim ignorance of the scientific norms and stages delineated by the Commission.

The pathway forward also suggests many national regulatory bodies and an International Scientific Advisory Panel to evaluate and update proposed uses of HHGE. These regulatory proposals now await the report by WHO.

For brief reactions to the report from fifty experts across a range of fields, see the October 2020 issue of The CRISPR Journal (Reactions to the National Academies/Royal Society Report on Heritable Human Genome Editing, The CRISPR Journal, 3,5).

*The views represented in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of the International Science Council or its Committee for Freedom and Responsibility in Science (CFRS).

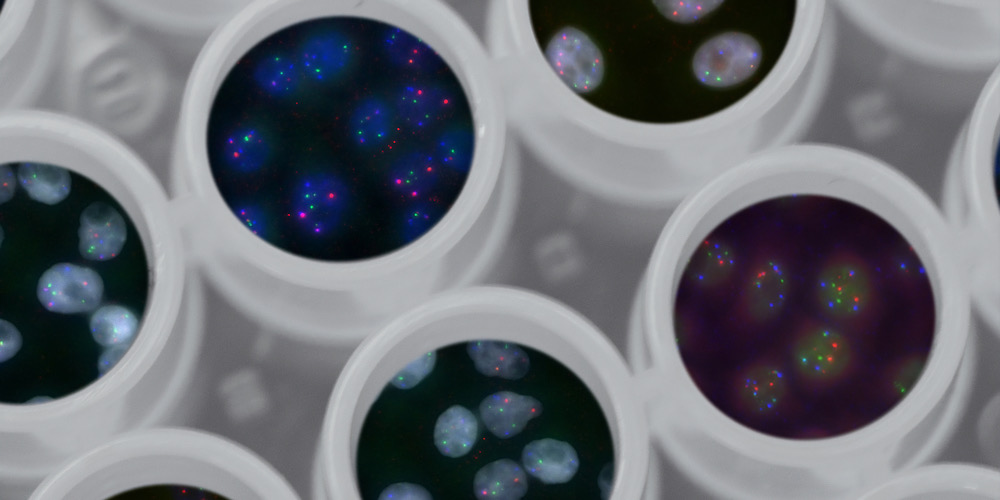

Heading photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash: Three-Dimensional Landscape of Genome.