ISC Presents: Science in Exile is a series of podcasts featuring interviews with refugee and displaced scientists who share their science, their stories of displacement and their hopes for the future.

The final episode of the series features political scientist Radwan Ziadeh, who shares his story of leaving Syria to continue his research on and advocacy for human rights and democracy in the United States. Radwan Ziadeh – who is a member of the Steering Committee for the Science in Exile initiative – tells us more about the kind of support that displaced and at-risk scholars need, what drives him to continue working for change, and his hopes for the future of Syria.

Radwan: The exchange ideas between me and the scholars in the field, between the academic community not only kept me alive, but also provide me with new ideas, new lenses to be able to see the Syrian conflict. And I learned a lot – this is actually one of the great benefits of the exchange between the scholars in the new communities and the scholars in the host countries.

Husam: I am your host Husam Ibrahim and this is the Science in Exile podcast. In this series, we get an insight in the lives of scientists who are in exile, and we discuss how the past, present and future of science can be preserved across borders. The podcast is a part of an ongoing refugee and displaced scientist initiative run by Science International.

On today’s episode we have Radwan Ziadeh, a member of the Science in Exile steering committee, a Syrian author of over 30 books pertaining to Middle Eastern – Western policy. He’s a Senior Fellow at the Arab Center in Washington DC, the Founder of the Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies, the Executive Director at the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies and the Managing Editor of the Transitional Justice in the Arab World Project.

Following many encounters with the Syrian Security Forces and threats of being imprisoned for his human rights activism, Radwan took a fellowship opportunity with the US Institute of Peace in order to continue his work as an academic and human rights activist in the United States.

Radwan: With the situation in Syria, at that time in the nineties, the difficult human rights abuses led me to be a human rights activist and more active in the writing about the future of Syria and the need of the basic freedom, like freedom of assembly, freedom of expression. It wasn’t easy, they took my passport, I was under government harassment, interrogation, travel ban, many many times.

When I wrote my book about Syria and decision-making process, and, of course, the book has been – as all my books – has been banned from Syria. I don’t know how the Syrian Security Forces gets hold of a copy of the book and they start interrogation, and I received a clear threat from the head of the security forces, he said – why you criticize the president, and who you are to be criticizing the president and next time you’d be in prison. When I left the office I was glad that I was still alive, and then I took the decision that there is no place for me here. I should try to leave Syria as soon as possible and also to continue my academic writing.

I felt all my basic rights under threat and then I accepted the fellowship I got from The US Institute of Peace. I managed to leave along with my wife into Jordan, then from Jordan into the United States where I start a new career. But also, still, I brought Syria with me in my heart. This is why most of my research and studies continue now around Syria, because I believe that Syria is witnessing today – it’s the tragedy of our times. This is the largest number of people being killed during a Civil War in recent history. And of course, now the Syrian spread in over 132 countries around the world according to the UN. The tragedy requires all the efforts of the Syrians and anyone actually the world to help Syria to be able to transition this dark history into more brighter future.

Husam: If you could have a conversation with the version of yourself who was about to leave Syria, what would you now say to him?

Radwan: Always, I revisit actually that decision and of all what’s going on in Syria I thought I took the right decision to leave Syria, because I don’t think now I have any chance to continue the work I’ve done in the last 10 years if I still inside Syria.

But of course, we lost our houses. My mother, or my sister or brothers, the whole family became refugees in Jordan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and in Germany. I haven’t been connected to even to my mother, or my sister or brothers for almost six or seven years. I haven’t seen them. But of course, the price I paid, it’s no way comparing to other who lost their beloved ones.

Husam: How has it been since you migrated to the US, how has your research and work evolved or changed? And what were the opportunities that allowed that change to occur?

Radwan: I mean, the United States has offered me a great opportunity to be part of one of the prestigious universities. I became visiting scholar at Harvard University, New York University, Georgetown, and Columbia University. I did lectures in most of the US universities also like Princeton, Stanford and others. The exchange ideas between me and the scholars in the field, between the academic community not only kept me alive, but also provide me with new ideas, new lenses to be able to see the Syrian conflict. I learned a lot and and this is actually one of the great benefits of the exchange between the scholars in the new communities and the scholars in the host countries. I grew up in authoritarian and closed society regimes where they always, they saw these new ideas as a threat to the state, as a threat to the country, and that’s a huge difference of course.

Husam: Do you have any colleagues who are still working in Syria? Also if so, what is their experience like working there?

Radwan: Yeah, I still have friends and colleagues who are living in Syria and looking for the opportunity to leave Syria. Now the economic situation in Syria has huge impact on the decision of the Syrians inside Syria to leave, because there are no state services, there is no electricity, no drinking water, and at the same time, the default of the Syrian pound, that create what we call a huge impact on the middle class. And of course, the cost of living inside Syria became very difficult for any Syrian who belong to the middle class or even upper-middle-class because of the inflation. All of that create an environment for most of the Syrian academics to look for ways to leave Syria rather than to stay and contribute. They see there is pessimism around the communities where they feel there is no hope, there is no light at the end of the tunnel and we should be able to leave in any way to start a new life.

Europe, it witnessed one of the largest wave of my refugees from Syria in 2014 and 2015. As an example, Germany hosted in one year, more than 700,000 Syrian refugees. This is why my recommendation to any host country is to encourage those Syrian refugees for more integration programmes, projects and policies rather than to exclude them from any type of funding or prevent them from getting any type of work permit, or prevent them from the best way into citizenship because I’ve seen in the last five years a lot of success stories, among the Syrian refugees. If they have the environment to continue their work, continue their research, that, it will be a great contribution and added value to the humanity and to the field.

As an example, four Syrian refugees succeed in the parliamentarian election in Germany. That will not happen without the integration that Germany put in place in the last decades. This is why it’s an example for other countries to do the same. That’s what help the Syrian refugees and also helped the host countries and it also will help the host countries and the host community overall.

Because the new host countries also, they need new forces in the marketplace and the Syrian refugees are happy to contribute and play a role in the growth of those new countries.

Husam: So what would you say to your fellow academics who are still in Syria?

Radwan: Don’t lose hope. I know the situation inside Syria is very tough and difficult and I know how hard it is to continue your work in your academic institutions inside Syria, but don’t lose hope because we still need any contribution from anyone, especially from the academic community and scientists community, those to contribute to the growth of any society and Syria needs you and your contribution.

Husam: As you know, the Science in Exile initiative draws on existing networks to convene different information available for refugee and displaced scientists. From your perspective, what can organizations and initiatives around the world do to be most effective?

Radwan: I do believe there is resiliency of the scholars and scientists in exile or the refugees those to be able to adapt with the new environment, and because they come with the attitude of appreciation.

I think there are some institutions who helped me and organizations who helped me. Of course when I came here as a fellow at US Institute of Peace, which is one of the largest research institutions here in Washington DC area. But always there are other areas you have to discover by yourself, like the social life, the political life, and in all of that. And I wish if I got some assistance in that areas, because we need a lot of tips and assistance from friends through the years to be able to accommodate all these changes.

Husam: Yeah, and as you know, in the weeks after this podcast has gone to air, the Science in Exile project will launch a declaration that calls on the global scientific and academic communities to develop a unified response to displaced and refugee scientists. Radwan, what do you hope that this declaration will achieve and why should the people listening take the time to find out more?

Radwan: This is something I’m proud to be part of it because I see myself in the declaration and I saw a future in such declaration with the help of this initiative and the new institutions be able to classify the scientists in exile or the scholar refugees as a class need certain protection, and need certain attention. With this declaration, I think we achieve that. The next step I think will be to be able to advocate on behalf of this declaration, to be an international declaration like the declaration for human rights in 1948. We are happy and proud of this moment and this declaration.

Husam: Yeah and it goes without saying that you’ve worked against a lot of oppression and injustice. But during your work within so many organizations, what has given you the most amount of hope for the future and what is it that motives you to keep going?

Radwan: Always actually, I’m optimistic and always I say optimism is a muscle and you have to use to get more stronger. I see a better future because I saw Syrian refugees everywhere be able to integrate and be able to excel within the new communities in record time, in two or three years, even they don’t know the language, they don’t know the economic system, the sophisticated way of life, but they still be able to actually adapt and excel. That gives me hope that despite of all the difficulties that the Syrian society is going through, we will be able to rise again, and be able to build the Syria or be proud of as a Syrian democratic country.

Husam: Yeah, and do you have any stories from your work as a human rights activist that still inspire you to this day?

Radwan: Yes. Of course, I have a lot but one of the stories always resonate with me in 2003, when I was in Syria and my organization Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies, we started to publish reports. And it’s a huge risk to publish a human rights magazine inside Syria, under the cover and secretly. And also, we distributed in secret way to the activists, to the interested people.

And I remember when I tried, when we printed the second edition of this human rights magazines – you can go in jail for ten years if the Syrian security detained you or arrest you and you have a copy of this magazine – And I remember one of the citizens who was in the street, took this magazine, he came to me and he said, ‘Are you okay?’ I said ‘yeah why?’ and he said ‘I think you are stupid because you are doing that and you know the risk of doing this’. And 10 years later the same person sent me an email, that he kept the copy and he’s now in Germany and he’s continued to work for the human rights in Syria. It’s amazing and every day I open this email because it gives me hope. I never imagined that and an unintended event like that can contribute to the will and the wellbeing of a person through his life. And this is why I always emphasize do the good thing. Even small things, it can contribute and change other people’s lives.

Husam: Thank you Radwan Ziadeh for being on this episode, and sharing your story with Science International.

This podcast is a part of an ongoing refugee and displaced scientists project called Science in Exile. It’s run by Science International, an initiative in which three global science organizations collaborate at the forefront of science policy. These are, the International Science Council, The World Academy of Sciences and the InterAcademy Partnership.

For more information on the Science in Exile project please head over to: Council.Science/Scienceinexile

The information, opinions and recommendations presented by our guests do not necessarily reflect the values and the beliefs of Science International.

Radwan Ziadeh

Radwan Ziadeh is a senior analyst at the Arab Center, Washington, DC. He is the founder and director of the Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies in Syria, and co-founder and executive director of the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Washington, DC. He was named “Best Political Scientist Researcher in the Arab World” by Jordan’s Abdulhameed Shoman Foundation in 2004 and in 2009 he was awarded the Middle East Studies Association Academic Freedom award. In 2010, he accepted the Democracy Courage Tributes award on behalf of the human rights movement in Syria, given by the World Movement for Democracy. Ziadeh wrote more than twenty books in English and Arabic; his most recent book is Syria’s Role in a Changing Middle East: The Syrian-Israeli Peace Talks (2016).

The information, opinions and recommendations presented by our guests are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the values and beliefs of Science International, an initiative bringing together top-level representatives of three international science organizations: the International Science Council (ISC) the InterAcademy Partnership (IAP), and The World Academy of Sciences (UNESCO-TWAS).

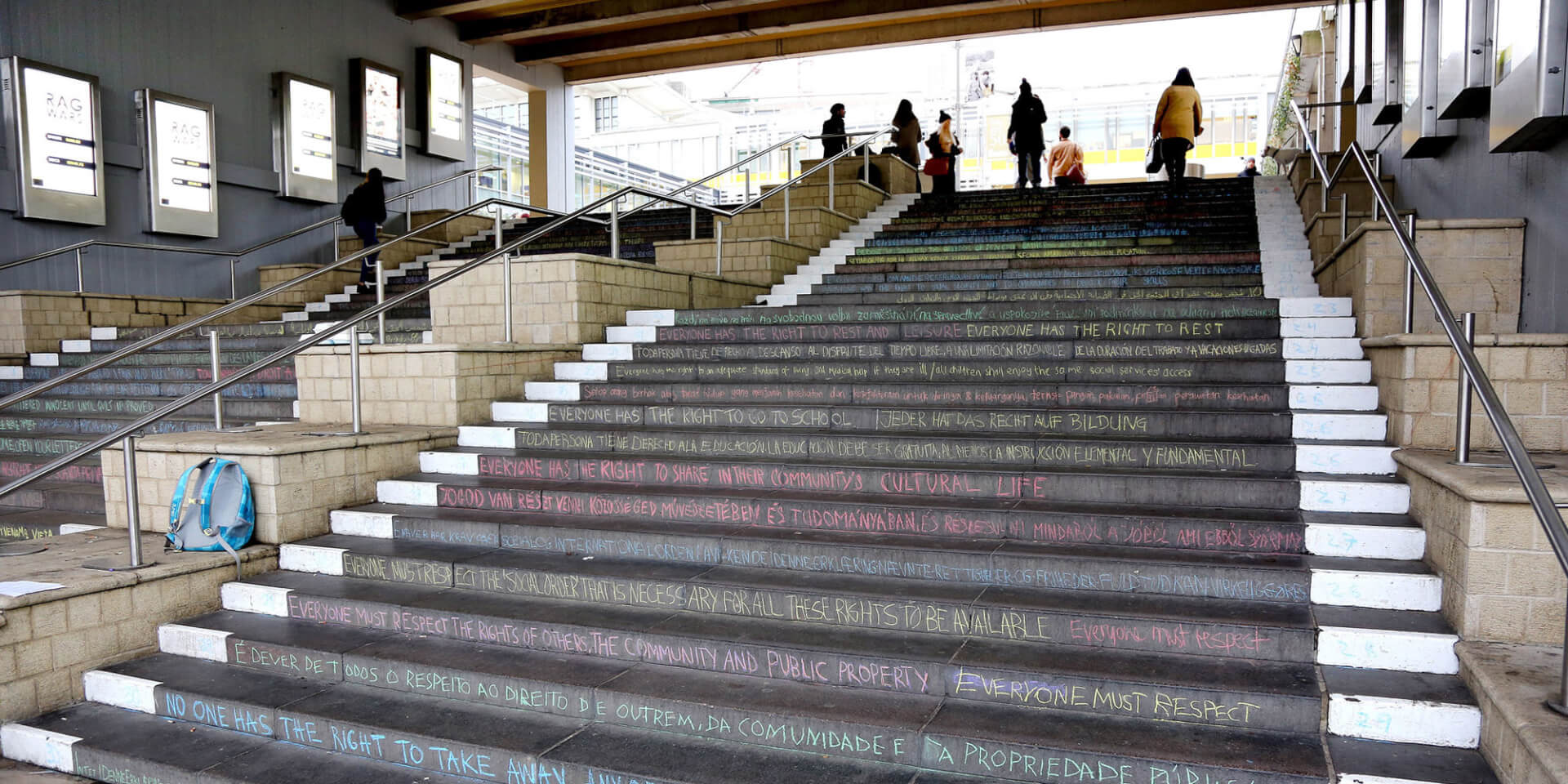

Photo: Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights chalked on steps at the University of Essex, UK (University of Essex via Flickr).