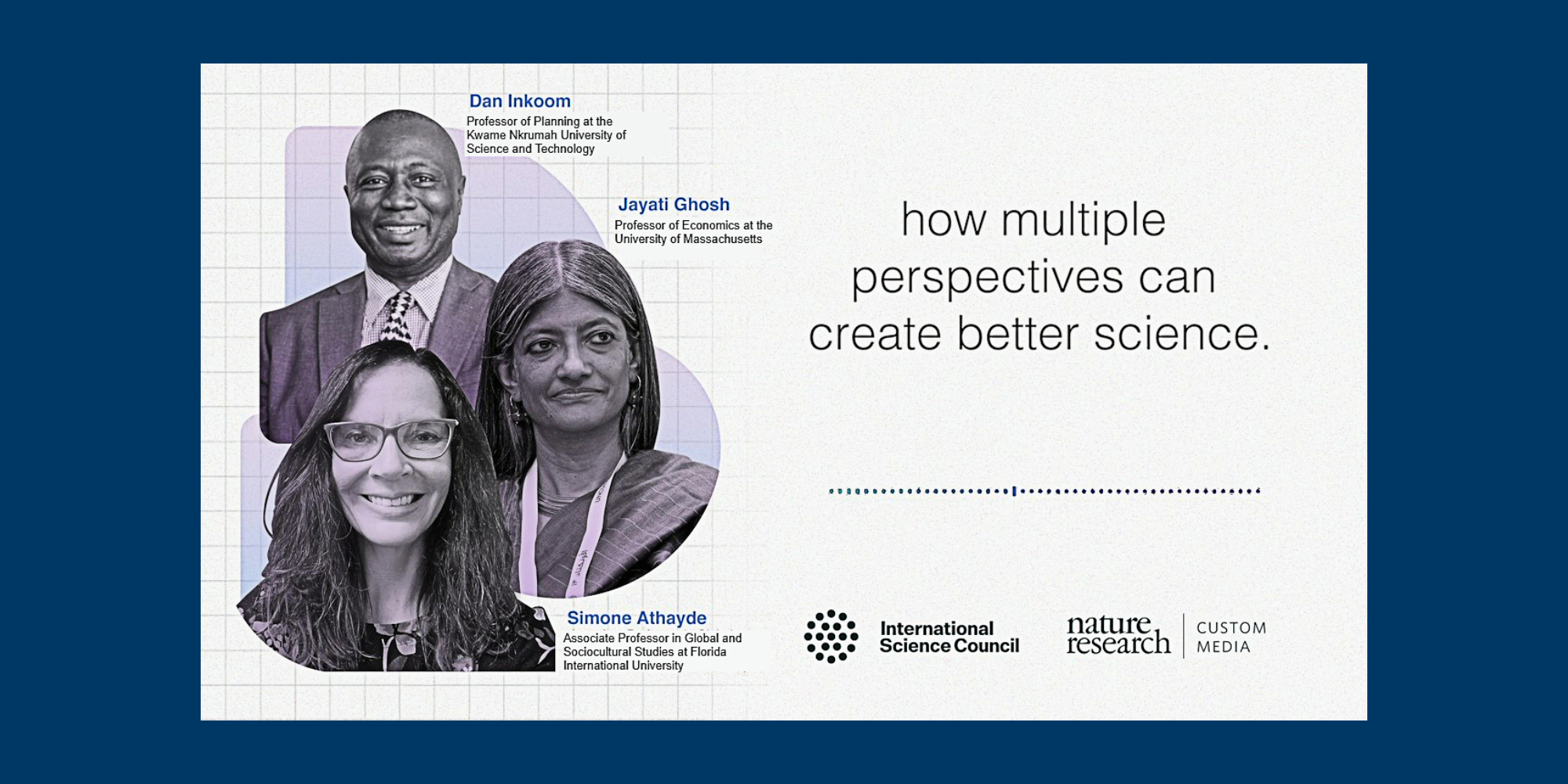

In the second episode of the Nature ‘Working Scientist’ podcast series featuring voices from the ISC’s network, we look at how including multiple perspectives can create better science. Jayati Ghosh argues that a lack of diversity in economics has made the discipline less able to actually understand the economy. Dan Inkoom discusses how so-called “ordinary people” in Ghana have much to contribute to his field of urban planning. And Simone Athayde explains how working with indigenous communities in the Amazon helped researchers to discover new things.

Listen to the podcast and find the full transcript below:

Transcript

Jayati Ghosh: All of the major problems of our time, the pandemic, climate change, the massive inequalities, the nature of fiscal responses and so on. The most interesting answers come from the economists who are largely ignored by the mainstream, and who are not taught to students in colleges and universities.

Marnie Chesterton: Welcome to this podcast series from the International Science Council, where we’re exploring diversity in science. I’m Marnie Chesterton, and in this episode, we’re looking at how multiple perspectives can create better science. Whether you’re devising Economic Policy, Planning a city, or protecting natural resources. Science is a team effort. All the sciences face complex challenges, which require diverse viewpoints, ideas and thinkers. But how can we put these ideals into practice? As part of a recent project, the ISC has been examining what the post pandemic age means for economics and diversity has been a key theme. According to Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, in Amherst in the US, it’s a discipline that needs to be more open to change.

Jayati Ghosh: I do feel that the economics discipline has actually got more and more impoverished over the last half century, because it has moved away from the recognition that economics is a social science or rather broadly, a study of society in its economic aspects, which means that it is necessarily more open to debate. That it is less purely scientific in terms of the absolute objectivity of certain conclusions. That it has more need to recognise the other social forces, political, anthropological cultural, power imbalances, it has to recognise all of those things, when it actually analyses the economy. We moved away from that to a notion of economics as being subject to some iron laws. And being very, very technical in the understanding. In a way that has diminished the discipline and has diminished our ability to actually understand the economy. We make models which are based on very restrictive assumptions, which somehow assumes that the underlying assumptions are correct. And they’re not. But economists are often surprised when the economic reality turns out to be very different. The global financial crisis was a famous example. I think the Queen of England famously remarked, why did none of you see it coming? Economists whom we call, you know, heterodox, or pluralist who have recognised these different possibilities. They had been warning for several years about the possibility of a very major crisis, but they were ignored. So I think the discipline has really lost by not coming clean, about the nature of the assumptions that guide the mainstream theories.

Marnie Chesterton: Jayati also argues that this lack of diversity in approach is affected by a lack of diversity in the people who are actually doing economics.

Jayati Ghosh: There’s a domination of what I call the North Atlantic, which is to say that economists based in the United States, the United Kingdom, and to some extent, Northern Europe, writing in English, get far greater recognition and acceptance than economists everywhere else in the world. If you look, just that, the Nobel Prize for Economics, I mean, who does it get awarded to over all of these decades. There’s been a lot of discussion of how you know, women often get excluded or marginalised. And certainly, there are very few women who make it to the top of the profession. Very few role models in that sense. There are, there’s a huge lack of diversity, even in the North Atlantic, in terms of people of different ethnic backgrounds, race, religion, and so on. Why does this matter? Because when you come from a particularly different reality, you are more aware of the assumptions that need to be changed, of the ways in which economic mechanisms play out differently for different groups. And that changes the way you do your science, that changes the way you do your analysis.

Marnie Chesterton: Luckily, though, things are changing. And there are those who want to make economics more permeable to different groups and voices.

Jayati Ghosh: And that’s because young people have come out in far greater number and across the world to demand change. Groups like the young scholars initiative, which has also grown massively in the last few years. Who are also questioning and they’re open. They’re saying, look, we are not going to exclude anybody. We want to hear all the different positions. And we want to expose ourselves to as many ideas, traditions and analyses as possible, so that we can judge for ourselves, which is the most applicable, which is the most relevant which truly advances our own knowledge.

Marnie Chesterton: This idea is at the heart of the ISC’s LIRA 2030 programme, which supports early career scientists in Africa, working to meet the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. What’s distinctive about the LIRA programme is that it promotes transdisciplinary research, integrating knowledge and perspectives from different scientific disciplines and from non-academics.

Dan Inkoom: The idea of transdisciplinary research involving other people, other disciplines, and local people, always has something to teach us, especially those of us who are academics.

Marnie Chesterton: This is Dan Inkoom, Professor of Planning at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana, where he’s been involved in LIRA 2030.

Dan Inkoom: Young grantees come into the process, and they are faced with the problem of having to cross disciplines to go into other fields to be able to, to engender this kind of cross-disciplinary research. I think the general sense is that it was quite exciting. And you found a large number of the grantees very enthusiastic and very open to stepping into new grounds and discovering things for themselves. And then you get those who are a bit sceptical about whether this will work at all.

Marnie Chesterton: Dan’s own field of research in urban policies is a focus of the LIRA programme. And it’s one that benefits hugely from the transdisciplinary approach.

Dan Inkoom: Essentially, I’m looking at how urban policies can influence the kind of things we see in the, in the urban landscape. And then who are the actors who are involved in the processes. I think the interesting thing is the perceptions of people who are educated people who are public servants, people who are privileged. Sometimes people have the notion and sometimes us academics as well, we have the notion that it’s a prerogative or it’s our preserve. And that in quotes, ordinary people do not know much about policymaking. And as a result, it is the enlightened, the educated, the elite, who will do the policy and later consult the people for their opinions. And that is sometimes shocking, because it tells you a lot about how people conceptualise the whole development process. And the fact that there’s a lot of exclusion from that whole process. And I personally think from my experience, that that is the reason why we see a lot of the issues that are unresolved in the urban landscape. The whole idea of transdisciplinary research is to accept that one discipline, one, let me say kind of knowledge alone, cannot respond to the complexity of urban issues that we face, and that there needs to be collaboration, there needs to be interdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary approach to resolving issues. And so once you have that at the back of your mind, then the so-called ordinary people also have something to contribute.

Marnie Chesterton: This more inclusive way of doing research, which values and utilises the contributions of so called ‘ordinary people’ is especially important when the outcomes of that research are going to impact those people.

Simone Athayde: I think it’s, it’s fundamental to have diverse perspectives and indigenous peoples have the long term experience and the bio-cultural connections, intersections between biological and cultural diversity. And I think that academia has a very important role to play in bringing these voices to the policymaking in supporting indigenous struggles.

Marnie Chesterton: This is Simone Athayde, associate professor in global and socio cultural studies at Florida International University. Simone is part of the ICS community of World Social Science fellows. In 2012. Her team was approached by indigenous communities who were concerned about several new dams that were under construction in the Amazon

Simone Athayde: So a couple of different indigenous leaders came to talk to me and to my colleagues to ask for support for their struggles and also to to challenge some of these studies that did not take their knowledge into consideration.

Marnie Chesterton: This led Simone and her colleagues to set up the Amazon Dams Network to promote transdisciplinary dialogue and coordinate research across Amazonian rivers, knowledge systems and people.

Simone Athayde: We realised that people were not talking to each other, researchers were not connecting their their topics, we’re not connecting their research, the research that existed were not properly communicated to, you know, to society and to different actors, and also that indigenous peoples were, and local communities were largely invisible in this process of hydropower development,

Marnie Chesterton: It was through working with indigenous communities to monitor the potential impacts of the dams that researchers were able to discover new things.

Simone Athayde: So we were developing the questions for the monitoring with them. And then something that the researchers did not think about was to also monitor the fruits that are used by the fish that are very important for you know, the fish to be sustained. And, and so they, they indigenous community said, hey, look, this fruit is super important, but we need to understand what the flow of the river have and the changes in the flow of the river will cause to these fruits. So all of that was like a lesson to us. And that was included in the monitoring questions. And in the monitoring programme.

Marnie Chesterton: The Amazon Dams Network also highlighted the importance of including women in research projects like this.

Simone Athayde: The indigenous women’s leadership was, was incredible for us to, to witness that, because you know. Women hold very different knowledge in comparison to man when it comes to the environment, it’s critical to have women’s participation and to hear women’s voices on these topics.

Marnie Chesterton: Bringing such a range of people and viewpoints together isn’t always easy. And there may be some who are against the inclusion of different types of knowledge in research or who are uncomfortable with it. But Simone has some advice on how to promote fruitful collaboration.

Simone Athayde: You need to be really welcoming and then use, you know, the theory of collaborative knowledge production, the theory of transdisciplinarity to, to involve them. And there are several tools and methods and things that you can use. And one of them is to use bridging concepts. For example, to ask questions about the values of rivers. For different people, different people will have different notions, different opinions, different worldviews on, on rivers and importance of rivers and, and when you ask those questions openly, other things can happen and even biophysical scientists can express something even more spiritual, that is connected to that worldview. And that can make them are more open to to hear and to listen to different perspectives. And then also setting the ground rules early in the process, which is to be more tolerant and inclusive of different, different perspectives help, because when there is any intolerance, you can bring back or remind people of what is our mission here, which is really learn from each other and to be more open and tolerant.

Marnie Chesterton: Simone, Dan and Jayati’s work show that knowledge is a shared journey. Requiring input from diverse groups. We each come to science with our own perspectives and experiences. And only by harnessing those, can we discover new things about the world, adapt to its challenges and help science advance. That’s it for this episode on diversity in science from the International Science Council. You can find out more about the LIRA 2030 programme, and the other projects mentioned in this episode online at council.science. Next week, we’ll be looking at improving gender diversity in science, including initiatives to give women a stronger voice in science organisations. And hearing from former President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, on why climate change is a man made problem in need of a feminist solution.

Jayati Ghosh is a development economist. She is Professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, USA. Her research interests include globalisation, international trade and finance, employment patterns in developing countries, macroeconomic policy, issues related to gender and development, and the implications of recent growth in China and India. She has authored and/or edited a dozen books and more than 160 scholarly articles.

Jayati recently participated in the ISC virtual event: Rethinking Economics in the Light of COVID and Future Crises – watch the video here.

Dan Inkoom is an Associate Professor at the Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, and Visiting Associate Professor, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dan recently participated in the ISC virtual event: Advancing the 2030 Agenda in African cities.

Simone Athayde is an Associate Professor with a joint appointment in the Department of Global and Sociocultural Studies (GSS) and the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (LACC) at FIU. She is trained as an environmental anthropologist and interdisciplinary ecologist, interested in advancing theoretical and methodological approaches for inter- and trans-disciplinary research and co-production of knowledge between the biophysical and the social sciences, as well as between academia and society.

Find out more about the Leading Integrated Research for Agenda 2030 in Africa (LIRA 2030) programme.

The World Social Science Fellows network, which is mentioned in this programme, was launched by one of the ISC’s predecessor organizations, the International Social Science Council, in 2012. The programme ended in 2015, and the network of 217 early-career scientists from around the world who participated in the programme continue to collaborate and connect with each other and with the ISC.

The ISC initiated this podcast series to further deepen discussions on broadening inclusion and access in scientific workplaces and science organizations, as part of our commitment to making science equitable and inclusive. The series highlights work being undertaken through different ISC programmes, projects and networks, and particularly ongoing initiatives on Combating systemic racism and other forms of discrimination, and on Gender equality in science. Catch up on all the episodes here.